- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 8134

Photo: abundantmama.com

Photo: abundantmama.com

Nearly a year ago I posted a Blog: In Praise of Frugality: Materialism is a Killer where I noted the following:

“A deadly force is taking over our world. This is a monster that can do too much harm to be so commonly welcomed into our society, and it goes by the name “Materialism.” The scariest thing about materialism is that it is so easy to fall into, especially in this day and age. So you ask what is materialism? It is a fixation on and love for material objects over actual living things”…

I then had posed some pertinent questions:

“How Much Is Enough? What is money and wealth for? Why do we as individuals and societies go on wanting more? What is economic growth for? Can we/ should we carry on just growing, creating, producing, consuming,…,more and more, for ever more? Do we need to satisfy our needs or our wants? Should we be a “maximiser” or “satisfier” and choose the path of “enoughness”? Then, what is a good life? What are the main ingredients of a good, happy and peaceful life? Should we move away from Gross National Product (GDP) to Gross National Happiness? What are we here for?”

Today I wish to share with you a possible path to how we might be able to achieve “Enoughness”.

As noted in a recent article in the Guardian, the Swedish term ‘lagom’ is the perfect term to describe an economic system where just enough is produced and consumed. Let me explain a bit more.

How to build a 'lagomist' economy

“The current capitalist economic system is in continual crisis. As Thomas Friedman, said in a New York Times op-ed: “What if the crisis of 2008 represents something much more fundamental than a deep recession? What if it’s telling us that the whole growth model we created over the last 50 years is simply unsustainable economically and ecologically and that 2008 was when we hit the wall, when mother nature and the market both said, ‘no more’.”

In the 21st century we need a new economic model to achieve a sustainable and equitable high quality of life for ourselves and our children. This model needs to go beyond the conventional “isms” (communism and capitalism) of the 20th century, all of which were focused on “growth at all costs”.

Getting the balance right between private, common and state property is critical to this new model. Communism (mostly common property) and capitalism (mostly private property) have both failed to get the balance right. The ongoing global economic and environmental crisis presents the opportunity to strike a new balance. Finding a path to sustainable prosperity requires that we achieve that balance.

We also need a new term to describe this model. We need a term that implies a better balance among built, human, social, and natural assets. We need a term that implies a shift from the “growth at all costs” economic model to one focused on sustainable human wellbeing – based on sufficiency, fairness and sustainability.

The Swedes have a term that connotes many of the qualities of such an economy. The term is “lagom”, which means “just the right amount”. The origin is from old Viking tales about passing a horn full of mead around the campfire and everyone taking just the right amount, so that there was still some left for the last person in the circle.

A “lagomist” economy would be one that was “just the right size or scale.” It is not an economy of scarcity and sacrifice. It is an economy where just enough is produced and consumed – no more, no less. An economy that had achieved “optimal scale”.

It would also be an economy where the benefits were equitably distributed, not only within the current generation of humans but also with future generations and with other species. It would be an economy where goods and services were valued and allocated efficiently, including the services of natural and social capital. These services are currently external to the market allocation system and are part of the open access commons.

A new, more nuanced suite of property rights and responsibilities that give adequate weight to the commons would also be a part of a lagomist economy. Public goods such as the atmosphere and ecosystem services that are currently open-access need property rights assigned to them to adequately protect them. However, we cannot (and should not) assign private property rights to these inherently common assets. We need new global institutions that can assign and enforce property rights on behalf of the global community. Such an institution could effectively charge for GHG emissions and use those funds to reward activities that remove carbon from the atmosphere or reduce emissions. One such institution that has been proposed is an “earth atmospheric trust”, just one example of the implementation of the public trust doctrine to manage our common assets.

A large and growing number of individuals and groups around the world have been discussing how this new economy needs to look. These include the New Economy Coalition, the International Society for Ecological Economics, the UN, the Future Earth Initiative, the Post Carbon Institute, the Alliance for Sustainability and Prosperity, and many others. A broad consensus is forming around the basic characteristics mentioned above. But everyone has a different name for it: ecological, green, regenerative, circular etc. That leaves the impression the consensus is weak. It is not. It is strong. But it will not crystalise until we have consensus on a common term to describe and encapsulate it. I propose lagom as that term.

By the way, it can also be used as a greeting, an affirmation of goodness and a toast.

Lagom!”

The above article was first published in the Guardian on Monday 6 April 2015:

How to build a 'lagomist' economy | Guardian Sustainable Business | The Guardian

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 204

A Few weeks ago I posted a Blog UK General Election 2015: Breakthrough for the common good – Dare to imagine that where I highlighted the serious need for us all to reflect carefully on life’s bigger picture and take action in the interest of the common good, as we contemplate and decide how to vote in the coming General Election on 7th of May.

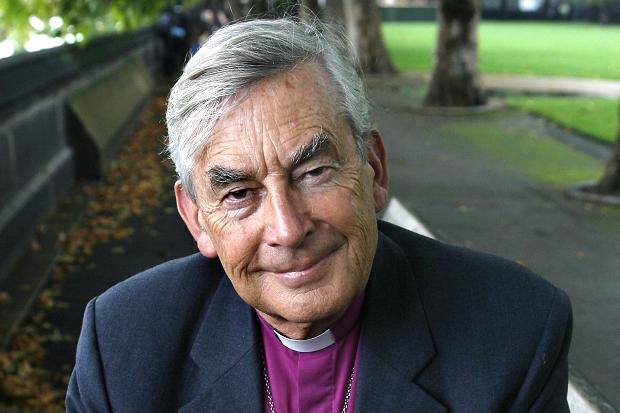

Today reading my Sunday papers I came across a very articulate and passionate article by the former Bishop of Oxford, Lord Harries of Pentregarth, whom I have had the pleasure of meeting a few times and who wrote the Foreword to the book- Promoting the Common Good- that Rev. Dr. Marcus Braybrooke and I had co-authored in 2005.

Lord Harries’ article is all about values, trust, integrity, morality, spirituality, ethics and more; and that all actions should be in the interest of the common good.

I very much enjoyed reading this article on this beatiful Easter Sunday, the day we all reflect on life’s bigger picture. The article also very much re-affirms the points and concerns I had raised in my Blog.

Let me share the article with you. I am sure you, too, will find it very interesting and relevant:

Faith in politics may be taboo, but we still crave a bit of morality

“There is something fundamentally askew in our public life today, as shown by the lack of trust in politicians and the alienation, particularly of young people, from the political system. This needs addressing first at the personal level by all those standing for public office. Surveys show that despite the terrible loss of trust in politicians in the past decade the public still expects the seven fundamental standards of public life to be observed.

Personal integrity is valued above rubies, while any party wanting to govern must believe, and convey the belief, that its policies are morally based; that they are for the benefit not just of a sectional interest but the common good.”

“I was talking recently to a serious-minded Conservative who is also a thoughtful member of the Church of England. She expressed distress that the bishops of her church continually seemed to advocate policies different from that of her party. For her there was a real relationship between her most fundamental beliefs and her political commitment. She was dismayed that this moral vision did not seem apparent to the leaders of her faith, a view echoed last week by David Cameron. I sympathised, and pointed out that there had been very little in the way of an intellectual Christian case for Conservatism for some time. The late Lord Hailsham put one forward some 50 years ago, as did Brian Griffiths (now Lord Griffiths of Fforestfach) at the time of Margaret Thatcher, but little else. No wonder that the Tories are widely perceived to be the defenders of those with assets, with hedge fund donors as their abiding symbol.

Traditionally the Conservative Party had a strong element of noblesse oblige. Alec Douglas-Home’s mother was heard to remark: “I think it is so good of Alec to do Prime Minister.” Where is that element now? A few do still enter politics, in part out of a sense of duty, but where is the vision of an Edmund Burke, perhaps the politician with the most deeply rooted and consistent moral sense in our history, who could legitimately be claimed by Conservatives as much as progressives?

Politics has always been about representing interests. It will be even more so after the election with the Scottish Nationalists, Plaid Cymru, the Greens and Ukip making it clear that they will expect a major quid pro quo for any role in supporting a minority government. This is a proper part of democratic politics. But if this is all that a party offers it cannot help but come across as thin and diminished. For with all our grievous failings we human beings remain moral beings. There is an altruistic side to the most selfish person, a charitable element in the most cut-throat capitalist. A party that wants to come across as more than a coalition of narrow interests must communicate a sense that it is working for the benefit of society as a whole. The British may not like overt appeals to religion but there remains a deep-seated sense of fairness in the population. We see this in the outrage at the way bankers can fail and still get their bonuses. We see it in the almost hopeless anger at the way our society seems to be in the grip of an international financial elite – and those who tuck into its slipstream – who can shift their cash to tax havens at will.

Labour starts from the opposite position. Drawing its strength from Methodist lay preachers and Roman Catholic trade unionists, as well as secular intellectuals; it has been a moral crusade or nothing. But there is a danger in moral visions. One is that powerful rhetoric can cover up a lack of thought-through policies. The other is to claim the high moral ground with the assumption that the other parties are driven only by self-interest. The British don’t like people who assume that only they have a moral position. The danger is very obvious in the case of religion, as we see in the contrast between the United States and Britain. In America, since the creation of a civic religion by Eisenhower and Truman, appealing to God is part of the rhetoric of any politician. Indeed there was a recent discussion about whether it would be possible for an atheist to be president. But in Britain the attitude was well summed up by Tony Blair, himself a religious man. When later asked why he did not bring religion more into the open when he was in power he replied that people would have thought him “a nutter”. The British do not like the assumption that God is only on one side of a debate, nor the assumption that morality belongs to one side only.

There is something fundamentally askew in our public life today, as shown by the lack of trust in politicians and the alienation, particularly of young people, from the political system. This needs addressing first at the personal level by all those standing for public office. Surveys show that despite the terrible loss of trust in politicians in the past decade the public still expects the seven fundamental standards of public life to be observed.

Personal integrity is valued above rubies, while any party wanting to govern must believe, and convey the belief, that its policies are morally based; that they are for the benefit not just of a sectional interest but the common good. And they must do this without appearing sanctimonious.

Lord Harries of Pentregarth is former Bishop of Oxford. His book 'Faith in Politics? Rediscovering the Christian Roots of our Political Values' (DLT) has been reissued with a new introduction for the election

The above article was first published in The Independent on Sunday 5 April 2015

Faith in politics may be taboo, but we still crave a bit of morality - Voices - The Independent

Further reading:

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 210

A Few weeks ago I posted a Blog UK General Election 2015: Breakthrough for the common good – Dare to imagine that where I highlighted the serious need for us all to reflect carefully on life’s bigger picture and take action in the interest of the common good, as we contemplate and decide how to vote in the coming General Election on 7th of May.

Today reading my Sunday papers I came across a very articulate and passionate article by the former Bishop of Oxford, Lord Harries of Pentregarth, whom I have had the pleasure of meeting a few times and who wrote the Foreword to the book- Promoting the Common Good- that Rev. Dr. Marcus Braybrooke and I had co-authored in 2005.

Lord Harries’ article is all about values, trust, integrity, morality, spirituality, ethics and more; and that all actions should be in the interest of the common good.

I very much enjoyed reading this article on this beatiful Easter Sunday, the day we all reflect on life’s bigger picture. The article also very much re-affirms the points and concerns I had raised in my Blog.

Let me share the article with you. I am sure you, too, will find it very interesting and relevant:

Faith in politics may be taboo, but we still crave a bit of morality

Lord Richard Harries

“There is something fundamentally askew in our public life today, as shown by the lack of trust in politicians and the alienation, particularly of young people, from the political system. This needs addressing first at the personal level by all those standing for public office. Surveys show that despite the terrible loss of trust in politicians in the past decade the public still expects the seven fundamental standards of public life to be observed.

Personal integrity is valued above rubies, while any party wanting to govern must believe, and convey the belief, that its policies are morally based; that they are for the benefit not just of a sectional interest but the common good.”

“I was talking recently to a serious-minded Conservative who is also a thoughtful member of the Church of England. She expressed distress that the bishops of her church continually seemed to advocate policies different from that of her party. For her there was a real relationship between her most fundamental beliefs and her political commitment. She was dismayed that this moral vision did not seem apparent to the leaders of her faith, a view echoed last week by David Cameron. I sympathised, and pointed out that there had been very little in the way of an intellectual Christian case for Conservatism for some time. The late Lord Hailsham put one forward some 50 years ago, as did Brian Griffiths (now Lord Griffiths of Fforestfach) at the time of Margaret Thatcher, but little else. No wonder that the Tories are widely perceived to be the defenders of those with assets, with hedge fund donors as their abiding symbol.

Traditionally the Conservative Party had a strong element of noblesse oblige. Alec Douglas-Home’s mother was heard to remark: “I think it is so good of Alec to do Prime Minister.” Where is that element now? A few do still enter politics, in part out of a sense of duty, but where is the vision of an Edmund Burke, perhaps the politician with the most deeply rooted and consistent moral sense in our history, who could legitimately be claimed by Conservatives as much as progressives?

Politics has always been about representing interests. It will be even more so after the election with the Scottish Nationalists, Plaid Cymru, the Greens and Ukip making it clear that they will expect a major quid pro quo for any role in supporting a minority government. This is a proper part of democratic politics. But if this is all that a party offers it cannot help but come across as thin and diminished. For with all our grievous failings we human beings remain moral beings. There is an altruistic side to the most selfish person, a charitable element in the most cut-throat capitalist. A party that wants to come across as more than a coalition of narrow interests must communicate a sense that it is working for the benefit of society as a whole. The British may not like overt appeals to religion but there remains a deep-seated sense of fairness in the population. We see this in the outrage at the way bankers can fail and still get their bonuses. We see it in the almost hopeless anger at the way our society seems to be in the grip of an international financial elite – and those who tuck into its slipstream – who can shift their cash to tax havens at will.

Labour starts from the opposite position. Drawing its strength from Methodist lay preachers and Roman Catholic trade unionists, as well as secular intellectuals; it has been a moral crusade or nothing. But there is a danger in moral visions. One is that powerful rhetoric can cover up a lack of thought-through policies. The other is to claim the high moral ground with the assumption that the other parties are driven only by self-interest. The British don’t like people who assume that only they have a moral position. The danger is very obvious in the case of religion, as we see in the contrast between the United States and Britain. In America, since the creation of a civic religion by Eisenhower and Truman, appealing to God is part of the rhetoric of any politician. Indeed there was a recent discussion about whether it would be possible for an atheist to be president. But in Britain the attitude was well summed up by Tony Blair, himself a religious man. When later asked why he did not bring religion more into the open when he was in power he replied that people would have thought him “a nutter”. The British do not like the assumption that God is only on one side of a debate, nor the assumption that morality belongs to one side only.

There is something fundamentally askew in our public life today, as shown by the lack of trust in politicians and the alienation, particularly of young people, from the political system. This needs addressing first at the personal level by all those standing for public office. Surveys show that despite the terrible loss of trust in politicians in the past decade the public still expects the seven fundamental standards of public life to be observed.

Personal integrity is valued above rubies, while any party wanting to govern must believe, and convey the belief, that its policies are morally based; that they are for the benefit not just of a sectional interest but the common good. And they must do this without appearing sanctimonious.

Lord Harries of Pentregarth is former Bishop of Oxford. His book 'Faith in Politics? Rediscovering the Christian Roots of our Political Values' (DLT) has been reissued with a new introduction for the election

The above article was first published in The Independent on Sunday 5 April 2015

Faith in politics may be taboo, but we still crave a bit of morality - Voices - The Independent

Further reading:

- Policies must be for the common good- Lord Harries of Pentregarth

- Prof. Mofid to Speak at the 5th International Conference on Integrating Spirituality and Organizational Leadership (ISOL) in Chicago

- Remembering my friend George Bull, OBE KCSG FRSL (1929-2001)

- Prof. Mofid to speak at World Congress of Faiths

- Has loneliness become the new normal?