A Few weeks ago I posted a Blog UK General Election 2015: Breakthrough for the common good – Dare to imagine that where I highlighted the serious need for us all to reflect carefully on life’s bigger picture and take action in the interest of the common good, as we contemplate and decide how to vote in the coming General Election on 7th of May.

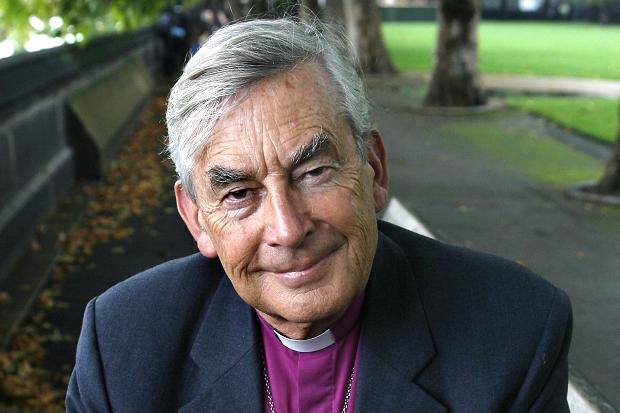

Today reading my Sunday papers I came across a very articulate and passionate article by the former Bishop of Oxford, Lord Harries of Pentregarth, whom I have had the pleasure of meeting a few times and who wrote the Foreword to the book- Promoting the Common Good- that Rev. Dr. Marcus Braybrooke and I had co-authored in 2005.

Lord Harries’ article is all about values, trust, integrity, morality, spirituality, ethics and more; and that all actions should be in the interest of the common good.

I very much enjoyed reading this article on this beatiful Easter Sunday, the day we all reflect on life’s bigger picture. The article also very much re-affirms the points and concerns I had raised in my Blog.

Let me share the article with you. I am sure you, too, will find it very interesting and relevant:

Faith in politics may be taboo, but we still crave a bit of morality

Lord Richard Harries

“There is something fundamentally askew in our public life today, as shown by the lack of trust in politicians and the alienation, particularly of young people, from the political system. This needs addressing first at the personal level by all those standing for public office. Surveys show that despite the terrible loss of trust in politicians in the past decade the public still expects the seven fundamental standards of public life to be observed.

Personal integrity is valued above rubies, while any party wanting to govern must believe, and convey the belief, that its policies are morally based; that they are for the benefit not just of a sectional interest but the common good.”

“I was talking recently to a serious-minded Conservative who is also a thoughtful member of the Church of England. She expressed distress that the bishops of her church continually seemed to advocate policies different from that of her party. For her there was a real relationship between her most fundamental beliefs and her political commitment. She was dismayed that this moral vision did not seem apparent to the leaders of her faith, a view echoed last week by David Cameron. I sympathised, and pointed out that there had been very little in the way of an intellectual Christian case for Conservatism for some time. The late Lord Hailsham put one forward some 50 years ago, as did Brian Griffiths (now Lord Griffiths of Fforestfach) at the time of Margaret Thatcher, but little else. No wonder that the Tories are widely perceived to be the defenders of those with assets, with hedge fund donors as their abiding symbol.

Traditionally the Conservative Party had a strong element of noblesse oblige. Alec Douglas-Home’s mother was heard to remark: “I think it is so good of Alec to do Prime Minister.” Where is that element now? A few do still enter politics, in part out of a sense of duty, but where is the vision of an Edmund Burke, perhaps the politician with the most deeply rooted and consistent moral sense in our history, who could legitimately be claimed by Conservatives as much as progressives?

Politics has always been about representing interests. It will be even more so after the election with the Scottish Nationalists, Plaid Cymru, the Greens and Ukip making it clear that they will expect a major quid pro quo for any role in supporting a minority government. This is a proper part of democratic politics. But if this is all that a party offers it cannot help but come across as thin and diminished. For with all our grievous failings we human beings remain moral beings. There is an altruistic side to the most selfish person, a charitable element in the most cut-throat capitalist. A party that wants to come across as more than a coalition of narrow interests must communicate a sense that it is working for the benefit of society as a whole. The British may not like overt appeals to religion but there remains a deep-seated sense of fairness in the population. We see this in the outrage at the way bankers can fail and still get their bonuses. We see it in the almost hopeless anger at the way our society seems to be in the grip of an international financial elite – and those who tuck into its slipstream – who can shift their cash to tax havens at will.

Labour starts from the opposite position. Drawing its strength from Methodist lay preachers and Roman Catholic trade unionists, as well as secular intellectuals; it has been a moral crusade or nothing. But there is a danger in moral visions. One is that powerful rhetoric can cover up a lack of thought-through policies. The other is to claim the high moral ground with the assumption that the other parties are driven only by self-interest. The British don’t like people who assume that only they have a moral position. The danger is very obvious in the case of religion, as we see in the contrast between the United States and Britain. In America, since the creation of a civic religion by Eisenhower and Truman, appealing to God is part of the rhetoric of any politician. Indeed there was a recent discussion about whether it would be possible for an atheist to be president. But in Britain the attitude was well summed up by Tony Blair, himself a religious man. When later asked why he did not bring religion more into the open when he was in power he replied that people would have thought him “a nutter”. The British do not like the assumption that God is only on one side of a debate, nor the assumption that morality belongs to one side only.

There is something fundamentally askew in our public life today, as shown by the lack of trust in politicians and the alienation, particularly of young people, from the political system. This needs addressing first at the personal level by all those standing for public office. Surveys show that despite the terrible loss of trust in politicians in the past decade the public still expects the seven fundamental standards of public life to be observed.

Personal integrity is valued above rubies, while any party wanting to govern must believe, and convey the belief, that its policies are morally based; that they are for the benefit not just of a sectional interest but the common good. And they must do this without appearing sanctimonious.

Lord Harries of Pentregarth is former Bishop of Oxford. His book 'Faith in Politics? Rediscovering the Christian Roots of our Political Values' (DLT) has been reissued with a new introduction for the election

The above article was first published in The Independent on Sunday 5 April 2015

Faith in politics may be taboo, but we still crave a bit of morality - Voices - The Independent

*Lord Harries in his article has referred to "seven fundamental standards of public life". What are they:

The 7 principles of public life

Committee on Standards in Public Life

Published 31 May 1995

1- Selflessness

Holders of public office should act solely in terms of the public interest.

2- Integrity

Holders of public office must avoid placing themselves under any obligation to people or organisations that might try inappropriately to influence them in their work. They should not act or take decisions in order to gain financial or other material benefits for themselves, their family, or their friends. They must declare and resolve any interests and relationships.

3- Objectivity

Holders of public office must act and take decisions impartially, fairly and on merit, using the best evidence and without discrimination or bias.

4-Accountability

Holders of public office are accountable to the public for their decisions and actions and must submit themselves to the scrutiny necessary to ensure this.

5- Openness

Holders of public office should act and take decisions in an open and transparent manner. Information should not be withheld from the public unless there are clear and lawful reasons for so doing.

6- Honesty

Holders of public office should be truthful.

7- Leadership

Holders of public office should exhibit these principles in their own behaviour. They should actively promote and robustly support the principles and be willing to challenge poor behaviour wherever it occurs.

See further:

The 7 principles of public life - GOV.UK

Further reading: