- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 1125

‘I can’t believe that this world can go on beyond our generation and on down to succeeding generations with this kind of weapon on both sides poised at each other without someday some fool or some maniac or some accident triggering the kind of war that is the end of the line for all of us.’-President Ronald Reagan, May 16, 1983

‘We are in the era of the thermonuclear bomb that can obliterate cities and can be delivered across continents. With such weapons, war has become, not just tragic, but preposterous.’-Dwight D. Eisenhower, Republican National Convention, August 23, 1956.

A Syrian boy, an innocent soul, walks with his bicycle, wondering why and what has happened to his beloved family, home, city and country.

Photo: afp.com

Imagining a Better World

The Path to the Heart of True Human Possibilities

A Poetic and Spiritual Pilgrimage to Wisdom to Build a Better World for All

O You Who’ve gone on Pilgrimage

Come, Come, Whoever You Are, Come

Ours is not a caravan of despair.

Ours is a Journey of Hope

What You Seek Is Seeking You ~ Rumi

‘To my mind, there is no doubt that, we need all the wisdom we can receive, especially in relation to the dark thoughts, the shame and the malice from which no person is immune. We need hope, love, beauty and wisdom to guide us in all we do. We need to be agents of goodness and light, whilst projecting them onto others. Taking this path, I am sure the world would, in due course, be less fractured and in pain than it is today.’ Kamran Mofid, A Poetic Pilgrimage to Wisdom

Poetry, literature and spirituality: The Language of Dialogue and Diplomacy

An Investment of Heart and Spirit: Balancing Humility and Ambition

It is worth remembering the centuries-old and timeless wisdom of the Persian poet, Sa’di:

Human beings are like parts of a body

Created from the same essence.

When one part is hurt and in pain,

the others cannot remain in peace and be quiet.

If the misery of others leaves you indifferent and with no feelings of sorrow,

You cannot be called a human being.

Another of his poems is inscribed at the entrance of the Secretariat of the United Nations in New York:

The Children of Adam

Are limbs of one another,

In terms of Creation,

They're of the self-same Essence

Poetry and literature: The language of dialogue and diplomacy

It may sound strange and irrelevant at glance to connect poetry, literature and spirituality (PLS) with politics or foreign policy in this so called digitized and gadget-driven age. However, the more I look, the way I see it, (PLS) are the perfect allegories that one must understand in order to envision a foreign policy that is built on diplomacy and dialogue for the common good, rather than relying on bombs and weapons.

(PLS) embodies the good and evil that exists in each one of us, and how one must strive to achieve the goodness, wisdom and beauty in spite of having evil qualities. If only politicians and policy makers chose to follow the path of dialogue, many wars and conflicts can be avoided. It is in each one of us to choose the path of dialogue, take actions in the interest of the common good, and achieve a lasting peace, building a world of harmony and prosperity for all and not a few.

To press this point further, I wish to share with the reader, a Blog I wrote a few years back, celebrating the successful nuclear treaty between Iran and the P5+1, reflecting on the words and philosophy of the Persian sage and poet, Farid al-Din 'Attar.

The more I read Attar’s poetry and the more I discovered about his philosophy, the more I realised that his poetry and literature promote the language of dialogue and diplomacy, very relevant to today’s needs to address the multiple global crises. His words, ideas and poetry foster human potential and the art of building true relations, nurturing dialogue, understanding, empathy and compassion to cultivate peace and harmony throughout the world.

In our troubled and suffering world of continuing and deepening crisis, our political leaders that take actions in our names, must show and stand up for a greater vision and courage, projecting honesty, humility and trust and invest not in shiny, new, smart missiles and boast about them, but, make substantial investment in wisdom, beauty, heart and spirit.

In order to show them a way in which this might be achieved, I can do no better than share what I had put together in an article in 2006 (updated in 2013 and again in 2015).

Iran and the US: A Mystic and Poetic Path to Conflict Resolution and Peacemaking

Kamran Mofid 6 May 2006

Dialogue: Our mystic Journey to Build a Better World

Kindness, love, compassion and forgiveness can unlock the door to peace in oneself, peace in others and then peace in the world

Life is a Journey of Transformative Dialogues of Self-Discovery of Knowing you, Knowing me

Photo:centerforpersonalevolution.com

As the Founder of the Globalisation for the Common Good Initiative, and as a person who has embraced spiritual economics, I always thought that there must be a better way, a more just path, to reconcile the West (US) and Iran. I felt that they must move away from concentrating mainly on the material aspect of their relationship to a more spiritual appreciation of who they are, what they believe in, what they share and what they have in common.

I strongly felt that this must be the first step, moving back from “All options are on the table”, and “Death to America - The Great Satan”, to a more meaningful dialogue for the Common Good: A Dialogue of Civilisations, the Dialogue of Discovery and Hope, celebrating our common humanity, kindness, trust, dignity, mutual respect and love.

But, the question was how this may happen, how it may begin? The answer, I believe, rests in Spiritual Diplomacy for the Common Good, choosing love which is the path to world peace with responsibility.

In a simplistic sense, as it has been noted, the idea is to see spirituality, universal human themes, religion and God as part of the solution to conflicts, as opposed to part of the problem. The tools and mechanisms that emerge from centuries of spiritual quests may provide a basis for communication, understanding and ultimate agreement.’ ... Continue to read

Photo:bing.com

Iran Nuclear Deal is truly the Triumph of Dialogue, Humility, Courage, Wisdom, Diplomacy, Hope and a Visionary Leadership; over Foolishness, Arrogance, Selfishness, Weakness, Fear, Extremism, Warmongering, and Short-sighted leadership. This has been a gift to the world. Long may it be so.

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 2369

Photo: bbc.co.uk

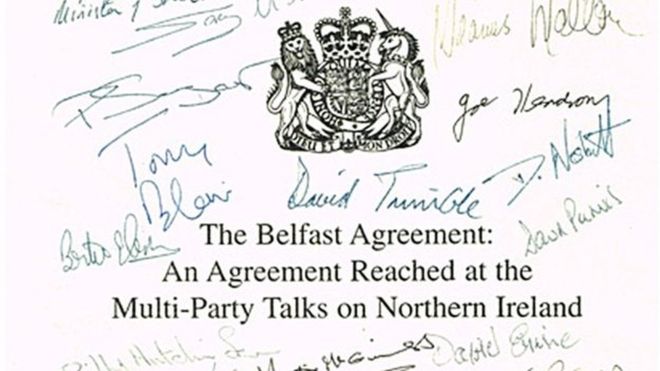

Today, Tuesday 10 April 2018, marks 20 years since the Good Friday Agreement (also known as The Belfast Agreement), which set in place terms that would bring peace to Northern Ireland.

The historic deal has brought Britain and Ireland closer than ever. However, today, Brexit has put the Agreement under a huge amount of stress and uncertainty.

In the words of former US secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, writing in today’s Guardian “We cannot allow Brexit to undermine the peace that people voted, fought and even died for. Reinstating the border would be an enormous setback, returning to the ‘bad old days’ when communities would once again be set apart.”

Clinton adapts a famous Blair quote from the time of the original Belfast agreement to warn: “If short-term interests take precedent over solving the long-term challenges that still exist in Northern Ireland, then, it is clear that the hand of history will be both heavy and unforgiving.”

To neglect the peace process now is a grave mistake

What, then, is the answer?

HOPE, I say

Hope for the region lies in the transformative power of forgiveness and reconciliation, lest we forget

Courage and good-heartedness to take action in the interest of the common good to build a lasting peace

It may sound strange to talk about ‘Hope’ in these challenging times in Northern Ireland. Despite a period of relative stability, peacebuilding and economic development, a sense of hopelessness and despair has taken over people’s life and sentiments about the peace process, togetherness, communities and neighbourly relationships.

At the time of writing, the Northern Ireland Assembly has not sat in Stormont since January 2017, amid a renewable heating scandal, and unionists and nationalists seem unable to resolve issues ranging from same sex marriage to the use of the Irish language in the region. Furthermore, issues related to Brexit and the Conservative Government's power sharing agreement with the Democratic Unionist Party is said to have threatened the peace brought by the Good Friday Agreement those 20 years ago.

To cut a very long and complicated story short, for me, reflecting back, looking at Northern Ireland today, I feel that, a great deal of political hopes have been realised beyond expectations and dreams. However, the current uncertainty calls for an urgent need for a deeper understanding and healing. The boil and the pains of bitterness, hurt and sectarianism has not yet been fully lanced. This has to change if the peace of the last 20 years is to continue.

Paraphrasing many comments that have been made already, it appears that, the underlying issues, affecting the Good Friday Agreement, are constitutional, as well as the need for forgiveness, repentance, truth, justice, as well as the core issues of identity – Irishness and Britishness.

In short, people need to ask of themselves: How do we live well as neighbours, and who is our neighbour?

This relational aspect of reconciliation is necessary for true healing to take place, not only in Northern Ireland, but, also in all places of conflict, wars, injustice and destruction.

No Future Without Forgiveness: ‘Forgive and forget’ will not do. ‘Remember and forgive’ is the Hopeful Path to Reconcile and Build Peace with Justice

The Good Friday Agreement anniversary is a chance to redouble the focus on duty to reach full reconciliation

To suggest a hopeful path for a better understanding of forgiveness, reconciliation, healing the wounds of the past, peace and justice, I can do no better that offer you the excellent and timeless address by former President of Ireland, Mrs. Mary Robinson, given at the launch of the Coventry Centre for the Study of Forgiveness and Reconciliation, delivered at Coventry Cathedral on Monday 11 March 1996.

'Forgiveness & Reconciliation'

Mary Robinson

The President of Ireland

(3 December 1990 – 12 September 1997)

Forgiveness & Reconciliation Mary Robinson

“I am deeply honoured to have been invited to inaugurate your Centre for the Study of Forgiveness and Reconciliation with this lecture, and to act as the Centre’s Patron.” -Mary Robinson, President of Ireland

Related Links:

Coventry and I: The story of a boy from Iran who became a man in Coventry

Former President F.W. de Klerk’s Address at Coventry Cathedral, 2 September 1997

Centre for the Study of Forgiveness and Reconciliation

Forgiveness and Reconciliation in Pursuit of the Global Common Good

‘Father Forgive’: Coventry Cathedral and my life's journey of discovery

What is the Good Friday Agreement that brought peace to Northern Ireland?

Listen to people of all ages reading aloud from the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement

‘The Belfast or Good Friday Agreement is now in its 20th year. We at times forget how important it was that the people of both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland voted for a future together.

In 1998 we witnessed the courage of people who crossed the constitutional divide when seeking accommodation and recognition of the need to build inclusive partnerships and values of tolerance and mutual respect. The Agreement has not been perfect and we have witnessed a range of political fallouts and disagreements but we have also witnessed a sustained decline in violence and new relationships that have formed across the sectarian divide.

We must never forget that the Agreement was the people’s process. It was the people who voted for it and they who sustained it through their commitment to creating a better society that one day will be released from the agonising grip of fear, intimidation and ultimately cultural and political futility.

Our obligation is not to merely remember the Agreement but to remind ourselves of one very central and important question.

What is my civic duty?

Let’s remind ourselves that 20 years after the Agreement that we must strive to build reconciliation, promote trust and most of all dedicate ourselves to a non-sectarian future.’

Prof. Peter Shirlow (FacSS), Director, Institute of Irish Studies, University of Liverpool

Watch the Video:

Listen to people of all ages reading aloud from the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 2795

Photo: tvokids.com

On 28 October 2014, I had posted an article In Praise of Kindness on the gcgi.info website. Let me quote you the introductory passage from that article, very relevant to what I am going to post below, continuing our thinking, reflection and pondering further on these hugely important questions: ‘What does it mean to be kind? What is Kindness?’

‘The reason we are losing our values is that we are failing to nourish them and hold on to them. It is a collective meanness of spirit.'

‘The Dalai Lama was once asked what surprised him most. He replied: "Man, because he sacrifices his health in order to make money. Then he sacrifices money to recuperate his health. And then he is so anxious about the future that he does not enjoy the present; the result being that he does not live in the present or the future. He lives as if he is never going to die, and then dies having never really lived."

Now let me share with you the words and sentiments of a young executive, a CEO, earning a lot of money, with bonuses, power, and more: “Now it's all about Productivity, Pay, Performance and Profit - the four Ps – which are fuelled by the three Fs: Fear, Frustration and Failure. Just sometimes I wish that in the midst of these Ps (& Fs), there was some time left for another set of four Fs: Families, Friends, Festivals and Fun.”

You see ladies and gentlemen, we need values, we need love, friendship, kindness, generosity, sympathy, empathy, and compassion to be the guiding principles of all we do. Otherwise, no amount of money, capital, technology, IT, theories and policies, can save us from our own mistakes, the crises of our own making.’ Kamran Mofid, “A Better Path”, School of Economic Science, Saturday 8 February 2014

Today, I wish to continue this reflection by sharing with you a very interesting and relevant article that I have recently read about issues related to a better understanding of ‘KINDNESS’. So, let me begin:

The Cult of Being Kind*

By Eve Wiseman, Via The Observer, Sunday 1 April 2018

Photo: lee-lo.co.uk/

“One cold morning in Bristol, a man named Gavyn Emery tied a scarf to a lamppost, and on a cardboard tag wrote: “I am not lost.” It was 2016, and rough sleeping in Bristol had risen by more than 800% in seven years. As temperatures plummeted, more people were inspired to do the same, wrapping trees in coats, sticking hats on bollards, warmth for anybody who needed it. Scarves started appearing in Cornwall, Glasgow, London, Cambridge; across the UK through this very long winter it was possible to see a blossoming compassion, visible in wool.

How a Random Act of Kindness in Bristol Became a National Movement to Help the Homeless

Photo: bristolpost.co.uk

What is Kindness?

Kindness is not new. It’s old, pretty old. Aristotle said: “It is the characteristic of the magnanimous man to ask no favour but to be ready to do kindness to others.” Kindness is mankind’s “greatest delight,” said Roman philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius. And yet, for a long time it has been seen as sort of… suspicious. As religion’s hold on our culture has weakened, and with it the insistence upon loving thy neighbour, a certain selfishness has come to be expected. To be kind is also to be weak, unfocused on achievement. Unsuccessful. Kindness is seen as a nostalgic throwback to simpler times, or worse, a con. A man who throws his coat over the puddle is a man who onlookers suspect must be protecting something valuable in the mud. To go out of one’s way to be kind suggests an ulterior motive – who has time to look up from their phone, let alone expose themselves to the discomfort of empathising with a stranger?

When Britain had just voted to leave the EU, the author Rachel Cusk wrote an essay about rudeness which she felt was “rampant”. “People treat one another with a contempt that they do not trouble to conceal,” she said. At the airport, she noticed strangers looking “suspiciously at one another, not sure what to expect of this new, unscripted reality, wondering which side the other person is on”. But as our new “reality” has bedded in, something is changing. Today, kindness is not only fashionable, appearing in a flood of news stories about everyday heroism, but it’s profitable.

Online, hashtags highlight small acts of kindness witnessed in public, and GoFundMe campaigns raise thousands for people in need. The publishing industry is calling the trend for kindness “up lit” – as in, illuminated from below, to expose one’s best angles. After a year of dark thrillers, today they’re investing in feelgood stories of empathy and care. Christie Watson’s The Language of Kindness comes out in May. A memoir about her career as a nurse, it sparked a 14-way bidding war and is being turned into a TV drama by the producers of Poldark. “If the way we treat our most vulnerable is a measure of our society,” she writes, “then the act of nursing itself is a measure of our humanity.” Through stories about her experiences with patients, she reminds readers that we will all, eventually, come to rely on the kindness of strangers.

Ahead of the launch of Jaime Thurston’s book, Kindness: The Little Thing That Matters Most, HarperCollins ran a campaign encouraging acts of kindness because, said Carolyn Thorne, editorial director: “Kindness is not just a book we are publishing but a chance to change cultural attitudes... When kindness is shared, it grows.” It grows. Literary agent Juliet Mushens, whose business partner Robert Caskie just sold debut author Libby Page’s novel The Lido for a fortune, twice – a story about a community, where a young woman befriends an 86-year-old widow to save a swimming pool – welcomes this move towards hopeful stories. “My feeling is that given the constant depressing news cycle, people are looking for a way to escape into fiction, and into more hopeful narratives.” She adds: “I would argue that these stories can be political in their own way. They can inspire the audience to fight for change on a personal level, and remind us that the individual choices we make can have a wider impact.”

‘When we are kind it doesn’t just help that person, it improves our own health’

Doing Good for the Common Good is Good for Us: A Proven Fact Now

Photo:bing.com

When Piers Wenger became the controller of BBC drama commissioning in 2016, he announced his intention to bring a lightness back to entertainment. “I think there is an awful lot of very dark drama across all channels and I’d love to see some more inspiring stories,” he explained. “I would love a Sunday night show which examines heroism and what it means to be a hero.” Note the preface “super” is missing. To be a hero today is simply to be a person who leans into the vulnerability that comes with seeing other people’s problems. It is to tie a scarf around a tree. Being a hero today requires no expert skills, no powers of flying or invisibility – in fact, one of the things that has helped devalue kindness over the past 30 or so years is the fact that we all know how to do it, we have done since we were children, but as a mark of our power and importance, choose not to. Being a hero today is to not look away.

Heroic storytelling extends to the news media, too. Open the New York Times and, since December, you will have found a column called The Week in Good News, right there on page two. A supercolony of penguins found near Antarctica, a SpongeBob musical, drugs that could delay prostate cancer… “The intention,” explains columnist Des Shoe, “is to provide an antidote to what can seem like an endlessly heavy news cycle.” Her column presents a curated selection of good news, including regular stories about “average people doing good work for others”. “I think people are yearning for good news because in the age of push notifications, the crush of stories about tragic things happening in the world can seem overwhelming.” We want a reminder that, despite the swamp of death and poverty we scroll through, all is not lost. This “yearning” means there’s a market for more. “People want good news. They spend time on good news, they seek it out and they look for more. Our readers have asked for much more of this type of coverage.” And stories of kindness lead to clicks.

Build a Better World: The Healing Power of Doing Good

The move towards kindness mirrors the rise of “happiness” pursuits earlier this decade, when a political interest in the value of happiness coincided with academic studies, a self-help movement towards joy, and the relentless counting of one’s blessings. In his book The Happiness Industry, William Davies reported that a growing number of corporations were employing chief happiness officers, while Google had its own “jolly good fellow”. Soon, happiness as a movement began to be questioned. It was pointed out that the political push for happiness grew as cuts in benefits and healthcare deepened. It coincided with a huge rise in prescribed antidepressants. Notions of happiness relied on a fuzzy vagueness: there was the suggestion that this noisy push for happiness was a way to displace attention from the causes of unhappiness itself.

But while happiness and kindness are undoubtedly linked, the difference is that happiness is passive, while kindness is active. At Springwell, for instance, a special school in Barnsley, where many students have suffered abuse, neglect or poverty, teachers have vowed to approach every child with what they call “unconditional positive regard” – or, as the principal Dave Whitaker says, they “batter the children with kindness”, and it seems to be working. Like happiness, kindness is difficult to quantify – we have no way of knowing whether people are becoming kinder, no apps to mine for data, few scarves to photograph – but we can count the stories of kindness that proliferate, often in tandem with those of the effects of austerity. A class of kids singing Happy Birthday to a stranger on the train; the ‘Pay it Forward’ movement; the “book fairies” hiding novels around Cornwall.

In the US this month, in the wake of teachers reporting higher anxiety in the classroom, a survey aimed to discover what children thought about kindness in the era of Trump. Only 14% “strongly agreed” their nation’s leaders “model how to treat people with kindness”. But researchers also noted an upward trend in social and emotional skills. While almost two-thirds said they had been bullied at some time, 8 in 10 said they’d gone out of their way to do something kind for another child, and nearly half said they have done so “many times”. Which is cheering, really, in the same way that Bristol’s scarves are – cheering with the lemon sourness of melancholy. Cheering, in that times have got so dark, with so many people in trouble, that we are finding new reservoirs of kindness and a new appetite for generosity. The concern is that children, with their easy kindness, still wet with lessons about “how to be nice”, soon grow up.

Kindness – “not sexuality, not violence, not money – has become our forbidden pleasure”, historian Barbara Taylor and psychoanalyst Adam Phillips wrote in their 2009 essay On Kindness. “Kindness is not just camouflaged egoism,” they insist. “To this old suspicion, modern post-Freudian society has added two more: that kindness is a disguised form of sexuality, and that kindness is a disguised form of aggression – both of which again reduce kindness to a covert selfishness.” They make the case that, due to these suspicions, we are all battling against our innate kindness.

It was 2013 and Jaime Thurston was scrolling through a second-hand furniture website when she came across a wanted ad: a single mother looking for a rug to cover her broken floor so her children wouldn’t cut their feet. Thurston, sensing desperation, called her and learned more about the situation she’d fled. It led to her starting a charity called 52 Lives, where people nominate “someone in need of kindness”. “We are living in a strange world,” she says, “a virtual world, full of comparison and isolation. We spend so long staring at our phones and avoiding real contact with people, and it ultimately makes us unhappier and lonelier. So I think people are searching for something fulfilling. I think kindness unlocks something deep within people.”

Does reading about kindness perform a similar function? Or, today are we seeking out stories of kindness in order to practise the action in our head before performing it – seeing these people in need, stretching the muscle memory required to offer a hand? By all accounts, we have got to this point through desperation. It was no longer viable to walk on by. “Kindness has so many benefits,” insists Thurston. “When we are kind to someone, it doesn’t just help that person, it is scientifically proven to improve our own physical and mental health as well. So at a time when rates of depression and anxiety seem to be skyrocketing, kindness could be a very simple but powerful antidote.”

In June, psychotherapist Padraig O’Morain publishes Kindfulness. He’s found that: “People who practise self-compassion, which is kindness towards oneself, are good at taking on challenges… It is often our own condemnation that we most fear.” Rather than random acts of kindness to others, O’Morain focuses on an inward-looking kindness. “It’s saying, ‘Look, even though you’ll never run a marathon before you go to work every day, or polish off your entire to-do list to universal applause by 11am, or become a tech billionaire before you’re 25, you’re OK, you’re fine, relax.’” Kindness then, to service the self.

Perhaps this is the key to the new wave of kindness. We perform kindnesses in response to darkness and, in turn, our lives are improved. Which means that rather than old-fashioned or altruistic, kindness is as modern as it gets. Is it rising not just because in cold times we’re compelled to offer scarves to those shivering, but because taking part makes us feel more successful? Well. Small steps, gently.”

*This excellent article by Eva Wiseman was first published in The Observer on Sunday 1 April 2018. See and read the original article.

- A Reflection on Monet’s timeless harrowing pleas for humanity to build a better world

- 14th GCGI International Conference and the 4th Joint GCGI-SES Forum, Lucca, 2018: Final Programme

- Book of Abstracts: 4th GCGI-SES Joint Conference 2018

- Easter is a declaration of hope, love, and renewal in a troubled world

- Water is Life and a Global Common Good: The Privatisation and financialisation of Water is a Crime Against Humanity