- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 1849

Selfishness

The Damning Impact of a Toxic Philosophy on the World’s Humanity: The Tragedy of Ayn Rand, Trump and the Fall of Humanity and Civility

Ayn Rand: The Woman who regarded altruism, selflessness, empathy, compassion and the common good as incompatible with man's nature, with the creative requirements of his survival, and with a free society!

(One wonders if by man’s nature and free society, she was referring to Trump and his Great America!!)- See below for more.

Ayn Rand: The Virtue of Selfishness. Photo:Getty Images

"It has a fair claim to be the ugliest philosophy the postwar world has produced. Selfishness, it contends, is good, altruism evil, empathy and compassion are irrational and destructive. The poor deserve to die; the rich deserve unmediated power. It has already been tested, and has failed spectacularly and catastrophically.”

Rand was a Russian from a prosperous family who emigrated to the United States. Through her novels (such as Atlas Shrugged) and her nonfiction (such as The Virtue of Selfishness) she explained a philosophy she called Objectivism. This holds that the only moral course is pure self-interest. We owe nothing, she insists, to anyone, even to members of our own families. She described the poor and weak as "refuse" and "parasites", and excoriated anyone seeking to assist them. Apart from the police, the courts and the armed forces, there should be no role for the government: no social security, no public health or education, no public infrastructure or transport, no fire service, no regulations, no income tax."...Continue to read

And now, given the tragic consequences of this toxic, immoral, uncivil, inhuman, untrue philosophy, once again, this ugly belief system has become the central agenda of a man who has captured the White House, whilst becoming a role model for other demagogues around the world.

Trump's Brand Is Ayn Rand

'Libertarian philosopher and author Ayn Rand has had a pernicious impact on many over the decades,

but Donald Trump and his gang of reactionary corporatists have showed just how far they are willing to go.'-Photo:commondreams.org

‘This far-right philosophy is an affront to the idea that we're all in this thing together.’

Rand and Trump Have Destroyed the Common Good (Robert Reich)

‘If there is no common good, there is no society

‘...In other words, we have to understand who Ayn Rand is so we can reject her philosophy and dedicate ourselves to rebuilding the common good.

The idea of the common good was once widely understood and accepted in America. After all, the U.S. Constitution was designed for “We the people” seeking to “promote the general welfare” – not for “me the selfish jerk seeking as much wealth and power as possible.”

Yet today you find growing evidence of its loss – CEOs who gouge their customers, loot their corporations and defraud investors. Lawyers and accountants who look the other way when corporate clients play fast and loose, who even collude with them to skirt the law.

Wall Street bankers who defraud customers and investors. Film producers and publicists who choose not to see that a powerful movie mogul they depend on is sexually harassing and abusing young women.

Politicians who take donations (really, bribes) from wealthy donors and corporations to enact laws their patrons want, or shutter the government when they don’t get the partisan results they seek.

And a president of the United States who lies repeatedly about important issues, refuses to put his financial holdings into a blind trust and then personally profits off his office, and foments racial and ethnic conflict.

The common good consists of our shared values about what we owe one another as citizens who are bound together in the same society. A concern for the common good – keeping the common good in mind – is a moral attitude. It recognizes that we’re all in it together.

If there is no common good, there is no society.’-Robert Reich, Trump's Brand Is Ayn Rand

Kindness the Antidote to Selfishness

“In a world where you can be anything, be kind.”

In a time of panic, please don’t forget to be kind.

How can we measure what makes a country great?

Imaging a Better World: Moving forward with the real Adam Smith

Adam Smith and the Pursuit of Happiness

A Must Read Book about how Adam Smith can change your life for better

Ayn Rand and the Cruel Heart of Neoliberalism*

Photo:softpanorama.org

'Trump is in most ways a Rand villain—a businessman who relies on cronyism and manipulation of government. Yet he praises The Fountainhead: “It relates to business, beauty, life and inner emotions. The book relates to . . . everything.”

‘In 2018, tech writer Douglas Rushkoff met with a handful of hedge fund billionaires to talk about the future of technology. But they were actually most interested in enlisting his help in filling in the details for their vision of the dystopian future—or rather, for their own high-tech vision of a Galt’s Gulch–style escape from it. Writing in Medium, Rushkoff described their questions about future apocalypse:

The Event . . . was their euphemism for the environmental collapse, social unrest, nuclear explosion, unstoppable virus, or Mr. Robot hack that takes everything down. . . .

They knew armed guards would be required to protect their compounds from the angry mobs. But how would they pay the guards once money was worthless? What would stop the guards from choosing their own leader? The billionaires considered using special combination locks on the food supply that only they knew. Or making guards wear disciplinary collars of some kind in return for their survival. Or maybe building robots to serve as guards and workers—if that technology could be developed in time. . . .

They were preparing for a digital future that had a whole lot less to do with making the future a better place than it did with . . . insulating themselves from a very real and present danger of climate change, rising sea levels, mass migrations, global pandemics, nativist panic, and resource depletion. . . .

Asking these sorts of questions, while philosophically entertaining, is a poor substitute for wrestling with the real moral quandaries associated with unbridled technological development in the name of corporate capitalism.

These unnamed hedge fund honchos may have read Atlas Shrugged, but even those who hadn’t would likely have been familiar with John Galt and the producers’ utopia he created far from the collapsing world. By 2018 Ayn Rand and her novels had become widespread cultural reference points among wealthy bankers, CEOs, tech moguls, and right-wing politicians.

Rand’s philosophy had its roots in nineteenth-century classical liberalism and in her impassioned rejection of socialism and the welfare state in the twentieth century. Her anti-statist, pro–“free market” stances went on to shape the politics of what came to be called libertarianism, or sometimes anarcho-capitalism, during a period of rapid expansion in the 1970s. The rise of neoliberalism has a parallel history, and much overlap with libertarianism—but these formations nonetheless have distinct trajectories. Rand’s influence floats over all of them as a guiding spirit for the sense of energized aspiration and the advocacy of inequality and cruelty that shaped their worldviews. By the 2018 meeting with Rushkoff, however, the billionaires could no longer be called optimistic. Their plans differ from Galt’s intention to return to save the world; the contemporary billionaires are only hoping to escape and survive the ruin—in high-tech style.

Ayn Rand bitterly rejected libertarians as right-wing “hippies” in the 1970s, but her views and those of her Objectivist followers melded substantially with the emerging libertarian movement. Young enthusiasts were joining older libertarian warhorses to create new organizations, publications, and institutions. Libertarian “rads” split from conservative “trads” in Young Americans for Freedom in 1969 and went on to help found the new Libertarian Party in 1971. The New York Times Magazine featured a major story that January tracking these developments: “The New Right Credo—Libertarianism.”

During the 1970s, chapters of organizations like the Society for Individual Liberty proliferated along with popular publications such as Reason magazine. A yearly libertarian studies conference, the Center for Libertarian Studies, and the Journal of Libertarian Studies established a foothold in academic life. The influential Cato Institute was originally opened as the libertarian Charles Koch Foundation in 1974. The libertarians, who clashed on a wide range of issues, ranged from countercultural left libertarians, to pragmatic advocates of a minimal state (“minarchists”), to a fiery right wing of adamantly anti-state anarcho-capitalists. Objectivists were prominent in all of their activities; reading Rand’s novels became a rite of passage for many. Rand herself disapproved of the lack of philosophical discipline among the motley crew of young libertarians, however, announcing that “if such hippies hope to make me their Marcuse, it will not work.”

Rand just got crankier and crankier as the years went by. She continued giving a few public lectures and publishing short essays on current events. She was interviewed by Phil Donahue; she began work on a television script for Atlas Shrugged that was never produced. Her health began a long decline when her lifetime of heavy smoking resulted in a diagnosis of lung cancer in 1974 (though she denied the connection between smoking and cancer to the end). She alienated nearly all her friends and colleagues one by one over the years, leaving only her heir, philosopher Leonard Peikoff, and a few others at her death in 1982. Objectivism, meanwhile, lived on—both in the loyal band of followers associated with the Ayn Rand Institute (founded by Peikoff in 1985) and in those who split off, feeling freer to branch out into more heterodox formations after Rand’s death.

As libertarianism spread and Rand withdrew, a new political economic formation began to take center stage. Becoming organized in the late 1940s with the establishment of the Mont Pelerin Society (MPS), neoliberal thinkers accumulated power and influence over the decades, to the point of seizing state power by the 1980s. Hard to define and largely hidden from view in the early years (the term was first used in 1925), neoliberalism was just one thread in the wild and woolly fabric of right-wing politics in the United States and Europe. The founding of the MPS helped define it as a distinct tendency among the classical liberals, Burkean traditionalists, libertarians, anarcho-capitalists, religious conservatives, right-wing racial nationalists, and fascists. Organized primarily by economist Friedrich Hayek, the more than one thousand economists, journalists, policy makers, and other thinkers who eventually gathered under the MPS umbrella formed what Philip Mirowski has called a “Neoliberal Thought Collective”—an intellectual/political intervention that eventually defined a new era of capitalism.

Although neoliberalism was never monolithic, the neoliberal project was focused on the need to develop a “new liberalism” to replace the outmoded concepts of nineteenth-century classical liberalism. The primary goal—remaking the infrastructure of states and markets in the post–Great Depression and post–Second World War world—did not comport with the “laissez-faire” capitalism of an earlier era. The neoliberals set out to retool the state in relation to the market values of property rights and corporate hegemony. While their public propaganda efforts emphasized the keyword freedom and linked so-called free markets with free minds, they set out via activist interventions in state policy to create a decidedly planned version of “laissez-faire.”

This gap between the public face and the relatively hidden political planning of neoliberals has been described by David Harvey as a contrast between the utopian theory of neoliberal freedom and the practical class project of installing oligarchical elites at the center of economic and state power. Neoliberalism is often misunderstood through its utopian propaganda as an effort to shrink the state and free the natural operations of “the market.” But neoliberals redirect state efforts rather than diminish them. The “Neoliberal Thought Collective,” combined with the various allied political policy centers of neoliberal action, might be understood as a global anti-left social movement. Nancy MacLean has traced the planning of various neoliberal forces—through foundations, think tanks, research centers and private funders—to create new barriers to democratic decision-making, in the interests of corporate power. She describes how Charles Koch was introduced to the thinking of Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin by anarcho-capitalist Murray Rothbard. Always learning from the left, Koch drew from Lenin’s thinking to develop plans for well-trained cadres that could prevail over a majority in the political arena. (Today, Lenin’s adherents on the right include former Breitbart editor and Trump adviser Steve Bannon.)

Neoliberalism was initially centered in Europe and the United States, focused on attacking the influence of John Maynard Keynes and the welfare states his thinking helped establish. The point of neoliberal effort was to free capitalism from the “mixed economies” that emphasized limited forms of social security, financial regulation, empowerment of labor, social services, and public ownership. The slow-motion collapse of the Fordist economies of secure employment, with relatively high wages and benefits, opened the door to new macroeconomic, monetary, and fiscal policies advocated by the Neoliberal Thought Collective—including privatization of public services, re-regulation of corporate operations, and erosion of consumer and workplace protections.

Though this process of “neoliberalization” was represented as race blind, many of the ideas and policies evolved out of resistance to the civil rights movement in the United States, via what Nancy MacLean has called “property supremacy.” Opposition to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was often articulated as a defense of private property against government interference, rather than as racial animus. Claims were made for the freedom of private property owners to discriminate against anyone for any reason. During “massive resistance” to civil rights in the U.S. South, the creation of private “segregation academies” sometimes displaced support for public schools—a model for later neoliberal strategies for privatization of education. But the critique of government institutions did not extend to legislative efforts to suppress voting rights and “law and order” police suppression of political dissent. In those circumstances state action was required to defend property rights from democracy as well as disorder.

In 1980, neoliberal politicians Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher ascended to become heads of state in the United States and United Kingdom. In subsequent years, neoliberal politics and policies moved social democratic parties unevenly toward neoliberalism all across Europe. During the 1990s the neoliberal Washington Consensus took form, and the 1992 Maastricht Treaty founded the European Union on neoliberal principles.

But the neoliberal political project was pursued far beyond Europe and the United States. Fundamentally, neoliberalism was a global extension of European colonialism on the nonterritorial U.S. imperial model. During the mid–twentieth century, former colonies throughout the Global South declared independence. New postcolonial states in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and the Caribbean instituted a range of strategies to establish growth and autonomy: restrictions on foreign investment, replacement of imports with local production, the redistribution of land, and the launching of ambitious public projects and social supports. Global neoliberalism was engineered to erode those strategies.

Violence was a central method for the imposition of neoliberalism in the Global South. The 1973 coup in Chile and the 2003 invasion of Iraq were both followed by foreign investment, resource extraction, and privatization of public assets. But the primary means for reestablishing the economic exploitation and political domination that are key to racial capitalism was the trap of debt.

Through lending to impoverished postcolonial states, financial institutions based in the Global North (especially the International Monetary Fund) were able to impose “structural adjustment” requirements on debtor nations in the South. After the 1989 fall of the USSR, neoliberalism entwined with various forms of postsocialist governance in states of the former Russian empire. Neoliberal policies also reshaped late twentieth-century China. More recently, forms of authoritarian neoliberalism mixed with right-wing populism are in ascendance in India, the Philippines, and elsewhere.

Neoliberal influence has been culturally deep as well as geographically wide. Drawing on the work of Michel Foucault, a multidisciplinary group of scholars have described the reach of neoliberal modes of governance into the conduct of everyday life. To counter the solidarity economies and social cooperation of organized workers, public-spirited officials, and professionals, neoliberals have promoted the Entrepreneurial Self who competes in the Aspiration Society. Everyone invests in their own personal and familial human capital, and all are responsible for their own risk-taking and rewards, or the lack of them. According to these conceptions, the poor are not a class, but a collection of individual failures. The rich are not exploitive parasites on the labor of the majority, but the very source of wealth and a boon to society. Except that, as Margaret Thatcher noted, “society” as such does not exist. The social is the context for individual striving. It is also the scene of the Neoliberal Theater of Cruelty, through which feelings of resentment, fear, anger, and loathing are enacted against the weak, who are a drain on the worthy. Cracking down on welfare “cheats,” “illegal” immigrants, and homeless “vagrants” can become a form of public satisfaction.

But the everyday life of neoliberalism—a template for living as well as governance—is not always so dramatic. Neoliberal cultures are multiple, and include “soft” multicultural, inclusive, and self-help–infused versions. Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, Barack Obama and Angela Merkel represent a range of softer versions. They have steered clear of the open-air theater of cruelty approach, while also busying themselves with stripping away the social safety net and backing the investor class—Bill Clinton abolished “welfare as we know it,” and Obama put Wall Street bankers in charge of dealing with the economic crisis in 2008. Under both soft and hard versions, everyday life is infused with the nuts-and-bolts preoccupations of neoliberalism more than with the spectacular—arranging medical care, purchasing insurance, checking credit scores, going to the gym, paying student loans, worrying about housing costs, getting kids into schools. The reorganization of the infrastructure of political and economic life has reached deeply into daily living, erasing many of the boundaries between “the market” and the body, the family, emotional life. Everyday preoccupations in neoliberal times center on surviving a precarious employment landscape and investing in the skills and traits needed to keep moving—rather than on building the solidarity that might underwrite a broad remaking of political and economic infrastructure. As a bus stop advertisement for New York University recently put it, “I am the CEO of Me, Inc.”

Then in 2007 and 2008, it looked like it all might come tumbling down. The collapse of the subprime mortgage market in the United States reverberated through global financial institutions, then infected markets and industries well beyond banking and housing. Losses were deep and broad. Neoliberal strategies of privatization, deregulation (especially of finance), and minimization of social services lost support in the short run. But their supporters soon recovered their nerve and Zombie Neoliberalism stalked the land. As Fredric Jameson and others have argued, economics is a story more than a science. And the story the Neoliberal Thought Collective told in the wake of the 2008 economic crisis was: More and better neoliberalism is the cure for, not the cause of, economic crisis. More tax cuts, less regulation, intensified theaters of cruelty! In Philip Mirowski’s phrasing, more “everyday sadism.” Those losing their homes are to blame for their bad mortgages; immigrants are to blame for citizens’ job losses and precarity; everyone should be responsible for their own healthcare! And in an especially tricky twist, the groups calling for neoliberal remedies for neoliberal crises (like the Tea Party) posed as outsiders—Fight the Power! Identifying the power became the crux of the problem.

During the decade since the crisis of 2008, politics have increasingly polarized in volatile ways around the world. The “center” of neoliberal consensus seems to be progressively collapsing, despite the strenuous efforts and significant successes of the Zombies. Left activism and right-wing mobilization have expanded rapidly. In this polarized landscape, Ayn Rand pops up as a kind of avatar of capitalist “freedom.” From a figure admired largely on the margins of U.S. politics, she moved into the political center in the decades after 1980—or rather, the center moved toward her.

Ayn Rand’s popularity has had four significant high points: (1) from the publication of The Fountainhead to the appearance of Atlas Shrugged (1943–1957); (2) among newly ascendant neoliberals during the 1980s; (3) among the new tech tycoons of Silicon Valley during the 1990s and after; and (4) during and after the 2008 crash. The link between the first two periods can be traced through the career of Alan Greenspan.

Greenspan became a regular at Rand’s Collective meetings during the 1950s, accompanying his first wife, Joan Mitchell. At first quiet and circumspect, Greenspan slowly waded into debates with Rand—who called him the Undertaker. He was a math whiz, a logical positivist, a committed empiricist technocrat when he encountered Objectivism. But then, he explains in his memoir The Age of Turbulence, “Rand persuaded me to look at human beings, their values, how they work, what they do and why they do it, and how they think and why they think. This broadened my horizons far beyond the models of economics I’d learned. . . . She introduced me to a vast realm from which I’d shut myself off.”

His work and reputation as an economic consultant took off during the 1960s, when he delivered lectures at the Nathaniel Branden Institute and published in the Objectivist. In 1974, as neoliberal thinking began to move increasingly away from pure forms of libertarian philosophy and toward the project of reshaping state power, Greenspan moved into a new post on President Gerald Ford’s Council of Economic Advisors (Rand and Frank O’Connor accompanied him to the swearing in). In his new location at the center of administrative power, he abandoned his advocacy of the gold standard and opposition to central banks. In 1987, he was appointed by President Reagan to be chairman of the Federal Reserve. From there until his retirement in 2006, Greenspan presided over the deregulation of the U.S.-based financial system.

Alan Greenspan thus became one of the most important neoliberal policy makers in world history. His rise to this position required compromises and shifts from his earlier, purist Objectivist views. Rand herself clung tightly to her integrated, uncompromising philosophy. She was thus not exactly a neoliberal herself—she shunned the negotiations required to retool the economic and political infrastructure as neoliberals aspired to do. She remained a propagandist, an Objectivist purist, and a drama queen presiding over her fictional Theaters of Cruelty, providing templates, plot lines, and characters for the everyday fantasies of the neoliberal era. She promoted the Entrepreneurial Self, attacked solidarity and socialism, and posed as the ultimate rebel, the icon of capitalist freedom. In this, she stood alongside rather than within the neoliberal project. Her spirit certainly guided major neoliberal institutions and publications—including the Cato Institute (directed from 2012 to 2015 by Objectivist and Ayn Rand Institute board member John Allison) and Reason magazine (founded in 1968 to support the Randian project of “free minds and free markets”).

Rand acolytes were spread throughout the world of business during the 1980s and ’90s, but the tech gurus of Silicon Valley have been an especially rich source of Ayn Rand fandom. As Nick Bolton explains in a 2016 issue of Vanity Fair,

Perhaps the most influential figure in the industry, after all, isn’t Steve Jobs or Sheryl Sandberg, but rather Ayn Rand. Jobs’s co-founder, Steve Wozniak, has suggested that Atlas Shrugged was one of Jobs’s “guides in life.” For a time, [Uber founder Travis] Kalanick’s Twitter avatar featured the cover of The Fountainhead. [Paypal founder] Peter Thiel . . . is also a self-described Rand devotee.

At their core, Rand’s philosophies suggest that it’s O.K. to be selfish, greedy, and self-interested, especially in business, and that a win-at-all-costs mentality is just the price of changing the norms of society. As one start-up founder recently told me, “They should retitle her books It’s O.K. to Be a Sociopath!” And yet most tech entrepreneurs and engineers appear to live by one of Rand’s defining mantras: The question isn’t who is going to let me; it’s who is going to stop me.

The Randian ethos of the heroic individual entrepreneur as alpha white male (and sometimes female) genius fits the self-mythologizing self-image of Silicon Valley tech startups particularly well.

It might have been expected that the bursting of the 1990s dot.com bubble and the early twenty-first-century financial crisis would have pulled the plug on some of these hot-air balloons. Even Alan Greenspan admitted during a 2008 congressional hearing that, “Yes, I found a flaw” in the ideology underpinning his deregulating fervor as chair of the Federal Reserve. But Ayn Rand rose with the Zombies after 2008, with a big sales surge for Atlas Shrugged. Tea Partiers and others saw the financial collapse and economic crisis as following the plotline of that novel. John Galt to the rescue meant . . . time for more and better neoliberalism.

The election of Donald Trump in 2016 would seem on the surface to constitute a repudiation of Randism. Trump is in most ways a Rand villain—a businessman who relies on cronyism and manipulation of government, who advocates interference in so-called “free markets,” who bullies big companies to do his bidding, who doesn’t read. His personal and public corruption mirror her character sketches of sellouts and dirtbags. Trump draws from nationalism in his rhetoric and some of his policies, and panders to religious conservatives—both ideologies Rand found odious. Yet he praises The Fountainhead: “It relates to business, beauty, life and inner emotions. The book relates to . . . everything.” His cabinet and donor lists are full of Rand fans.

The question arises with the election of Trump and the success of far-right nationalism and populism around the world—are these still neoliberal times? Are the Zombies reinforcing their infrastructure and deepening their hold with policies like the U.S. tax cut bill, the appointment of neoliberal judges, the extended privatization of healthcare and education, the gutting of environmental regulations that businesses oppose? Or is neoliberalism collapsing? Are we seeing the rise of security states and fascist parties that might replace neoliberal hegemony with something new—something terrifying? Or might we see socialist organizing reach toward something more egalitarian and inclusive, something exciting? The reign of the cruel optimism of Mean Girl Ayn Rand is one barometer. Rand cannot be a presiding spirit for right-wing nationalism or for socialism. She is the avatar of capitalism, in its militant form as market liberalism. If neoliberalism crashes and burns in public acceptability, so does she.

What can we all do? Organize, of course, as so many on the global feminist, antiracist, anti-neoliberal left are now doing. But also, expose the cruelty at the heart of neoliberalism, and build on the social solidarity she worked so hard to discredit and destroy. Reject Ayn Rand. After all, she rejects you.’

*This article by Lisa Duggan was originally published in Dissent Magazine on May 20, 2019.

Read the Must-Read Book by Lisa Duggan

University of California Press, May 2019

Also See: Is Neoliberal Economics and Economists 'The Biggest Fraud Ever Perpetrated on the World?'

The Ultimate Selfishness of Randism and Trumpism

Photo: pinterest.co.uk

Super-rich jet off to disaster bunkers amid coronavirus outbreak

‘Self isolate’ for some of world’s richest means Covid-19 tests abroad, personal medics and subterranean hideouts

‘Like hundreds of thousands of people across the world, the super-rich are preparing to self-isolate in the face of an escalation in the coronavirus crisis. But their plans extend far beyond stocking up on hand sanitiser and TV boxsets.

The world’s richest people are chartering private jets to set off for holiday homes or specially prepared disaster bunkers in countries that, so far, appear to have avoided the worst of the Covid-19 outbreak.

Many are understood to be taking personal doctors or nurses on their flights to treat them and their families in the event that they become infected. The wealthy are also besieging doctors in private clinics in Harley Street, London, and across the world, demanding private coronavirus tests.’...Continue to read

..And now lest we forget:

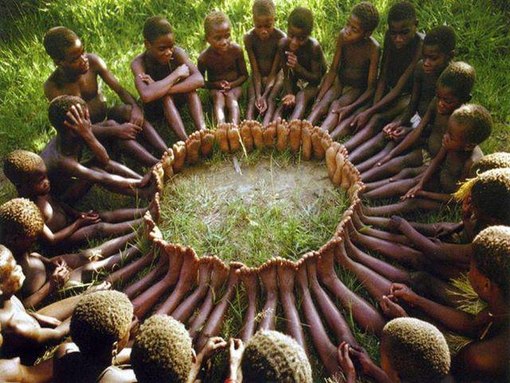

Rand, these are the true human beings, representing the true human values and what makes us all human, not you, Trump and others like you two.

Ubuntu : “I Am because We Are”

Photo:What is this life if…?

I would like to close with a story that illustrates “Generosity of Spirit of Selflessness” to perfection: An anthropologist proposed a game to children in an African tribe. He put a basket of fruit near a tree and told the children that whoever got there first would win the sweet fruits. When he told them to run, they all took each other’s hands and ran together, then sat together enjoying their treats. When he asked them why they had run like that, since one of them could have had all the fruits for himself, they said: “Ubuntu, how can one of us be happy if all the others are sad?”

Read more: Build a Better World: The Healing Power of Doing Good

Today is World Kindness Day: Embracing Kindness to Defeat the Political Economy of Hatred

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 1188

A study of beads made from ostrich eggshells, used to strengthen social networks, to ensure cooperation during tough times, suggests the humans of the Kalahari Desert region came together, founded ‘insurance policies’, and took actions in the interest of the common good, to help each other, as long as 30,000 years ago.

'Humans Have Been Taking Out Insurance Policies for at Least 30,000 Years'*

'Ostrich eggshell beads were exchanged between ancient hunter-gatherers living in distant, ecologically diverse regions of southern Africa, including deserts and high mountains.'

(Image courtesy of Brian A. Stewart, Yuchao Zhao, and the University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology/John Klausmeyer), Via Smithsonian Magazine

‘Foragers today who live in southern Africa's Kalahari Desert know that a drought or war can threaten their community's survival. To mitigate these risks, they enter into partnerships with kin in other territories, both near and far, so that if they have a bad year, they can head to another area to gather water and food.

"It's a really good adaptation to a desert environment like the Kalahari, which has huge spatial and temporal variability in resource distribution," says Brian Stewart, an archaeologist at the University of Michigan. "It can be very rainy in one season and in the next absolutely dry, or it can be very rainy in your area and then 10 kilometers away, it's just nothing." According to new archaeological research led by Stewart, this kind of partnership—which acts as a kind of insurance against one side of the partnership having a down year—has been happening for at least 30,000 years.

In the study, which was published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Stewart and his colleagues examined ostrich eggshell beads found during archaeological excavations at two high elevation rock-shelters in Lesotho, a country enclaved within South Africa. Since the 1970s and 1980s, archaeologists have been finding finished beads made from ostrich eggshells at prehistoric campsites in the area, Stewart says, even though ostriches are notably absent from the region. Based on this fact, and on anthropologists' comparisons with the systems used by modern hunter-gatherers, scientists assumed the ostrich beads to be part of the foragers’ long-distance insurance partnerships. That is, people from many miles away brought the beads and traded them to cement the social ties needed to ensure cooperation when one group of people endured tough times.

"Because of how effective this system is at shoring up risk, it's been used by a lot of archaeologists as a blanket explanation for why people exchange stuff," Stewart says. But, he adds, this idea hadn't really been tested for the archaeological record.

To figure out where the beads from Lesotho were created, Stewart and his colleagues examined their strontium isotope levels. Earth’s crust is abundant with a slightly radioactive isotope of rubidium that, over time, decays into strontium. As a result, different rock formations have different strontium signatures, and local animals can acquire those unique signatures via food and water. In this way, researchers can figure out where a 30,000-year-old ostrich came from.

"Now with globalization and our food moving all over the place—we can eat avocados in December in Boston, for instance—our strontium signatures are all messed up," Stewart says. "In the past, they would have been more pure to where we're actually from."

‘The natural instinct of human beings is towards cooperation and sharing. However, distorted by competition, personal ambition and nationalism, self-interest and greed have become pre-eminent motivating forces, distorting action and corrupting the policies of governments.

Competition is a pervasive element within all aspects of contemporary society, it is thought by many to be a positive and natural part of the human condition, and one that drives innovation and change. Loyal believers in competition assert that in the world of business it serves the consumer by driving down prices and creating virtually unlimited material choice, and will, some claim, be the driving force for environmental salvation. To be blessed with a competitive spirit, it is argued, strengthens an individual’s ability to succeed and overcome rivals; it stimulates “development” and advances in all areas — after all, if the urge to compete and achieve were negated, then what would motivate action?...

‘Cooperation is a fundamental quality of the time; it sits within a trinity of the age alongside unity and sharing. The expression of each of these galvanising principles strengthens and expands the manifestation of the other two; cooperation naturally evokes acts of sharing, which builds unity. Likewise, when we unite, cooperation and sharing occur. The introduction of these essential principles of change into all areas of contemporary life will lay a foundation of social harmony and allow the socio-economic structures to be re-imagined to meet the needs of all.’

Text and Photo: The need for cooperation and unity

The study showed that the majority of the beads from the Lesotho rock shelters were carved from the eggshells of ostriches that lived at least 60 miles (100 km) away. A few even came from about 190 miles (300 km) away, including the oldest bead, which was about 33,000 years old. "The really surprising thing was just how far they were coming in from, and how long that long distance behavior was going on," Stewart says.

"It's a really good adaptation to a desert environment like the Kalahari, which has huge spatial and temporal variability in resource distribution," says Brian Stewart, an archaeologist at the University of Michigan. "It can be very rainy in one season and in the next absolutely dry, or it can be very rainy in your area and then 10 kilometers away, it's just nothing." According to new archaeological research led by Stewart, this kind of partnership—which acts as a kind of insurance against one side of the partnership having a down year—has been happening for at least 30,000 years.

In the study, which was published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Stewart and his colleagues examined ostrich eggshell beads found during archaeological excavations at two high elevation rock-shelters in Lesotho, a country enclaved within South Africa. Since the 1970s and 1980s, archaeologists have been finding finished beads made from ostrich eggshells at prehistoric campsites in the area, Stewart says, even though ostriches are notably absent from the region. Based on this fact, and on anthropologists' comparisons with the systems used by modern hunter-gatherers, scientists assumed the ostrich beads to be part of the foragers’ long-distance insurance partnerships. That is, people from many miles away brought the beads and traded them to cement the social ties needed to ensure cooperation when one group of people endured tough times.

"Because of how effective this system is at shoring up risk, it's been used by a lot of archaeologists as a blanket explanation for why people exchange stuff," Stewart says. But, he adds, this idea hadn't really been tested for the archaeological record.

To figure out where the beads from Lesotho were created, Stewart and his colleagues examined their strontium isotope levels. Earth’s crust is abundant with a slightly radioactive isotope of rubidium that, over time, decays into strontium. As a result, different rock formations have different strontium signatures, and local animals can acquire those unique signatures via food and water. In this way, researchers can figure out where a 30,000-year-old ostrich came from.

"Now with globalization and our food moving all over the place—we can eat avocados in December in Boston, for instance—our strontium signatures are all messed up," Stewart says. "In the past, they would have been more pure to where we're actually from."

The study showed that the majority of the beads from the Lesotho rock shelters were carved from the eggshells of ostriches that lived at least 60 miles (100 km) away. A few even came from about 190 miles (300 km) away, including the oldest bead, which was about 33,000 years old. "The really surprising thing was just how far they were coming in from, and how long that long distance behavior was going on," Stewart says.

Archaeologists have documented, in the Kalahari and elsewhere, the deep history of long-distance movements of utilitarian items such as stone tools and ochre pigment, which can be used as a sunscreen or a way to preserve hides. In East Africa, researchers have recorded instances of obsidian tools being carried more than 100 miles (160 km) as early as 200,000 years ago.

"When you have stone or ochre, you don't really know that this exchange is representing social ties," says Polly Wiessner, the anthropologist who first documented the exchange partnerships among the Ju/’hoãnsi people in the Kalahari Desert in the 1970s. "However, these beads are symbolic. This is one of our only sources for such early times to understand social relations."

Wiessner suspects that the closer-range ties—the ones around 60 miles—that Stewart and his colleagues found indeed represent people who pooled risk and shared resources. However, she says, it’s possible that the few examples of beads that came from further away could have been acquired through trade networks.

"Often at the edge of risk-sharing systems, feeder routes extend to bring in goods from other areas by trade or barter and so the recipient does not know people at the source," says Wiessner, who wasn't involved in Stewart’s study but reviewed it for the journal. "It doesn't mean people had face-to-face contact from that far away."

Wiessner points out that people living 30,000 years ago were anatomically modern humans, so she would expect them to have large social networks. Similarly, Lyn Wadley, an archaeologist with the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, says, "I think that gift exchange is likely to have a much earlier origin." Wadley, who has studied the social organization of Stone Age hunter-gatherers but wasn't involved in the new study, also found the results convincing.

The new study suggests that the exchange network would have spanned at least eight bioregions, from arid scrubland to subtropical coastal forests. Stewart and his colleagues speculate that the system may have arisen during a period of climate instability, when access to a diversity of resources would have been crucial.

"This is just another piece in the puzzle of the incredible flexibility of our species," Stewart says. "We are able to innovate technologies that just make us so good at adapting very quickly to different environmental scenarios."

*This article by Megan Gannon was first published in Smithsonian Magazine on 9 March 2020.

Related reading:

In a time of panic, please don’t forget to be kind.

“In a world where you can be anything, be kind.”

...And Now Lest We Forget

Why We are Living Through an Epidemic of Selfishness and Greed

Photo:eand.co

The Age of Inhumanity: Selfishness, Competition, Digitalisation, Virtuvalisation and Neoliberalisation, Creating a Zombie World!

The shaming of a bunch of demagogue political, economic and educational leaders that have fooled the world, pushing a SELFISH and Parasitic ideology and philosophy on the world, with tragic outcomes and consequences.

The Damning Impact of a Toxic Philosophy: The Tragedy of Ayn Rand

The Damning Impact of a Toxic Ideology: Neoliberal Legacy of Thatcher and Reagan

The Damning Impact of a Toxic Ideology: Neoliberal Legacy of Koch Brothers

Is Neoliberal Economics and Economists 'The Biggest Fraud Ever Perpetrated on the World?'

Neoliberalism destroys human potential and devastates values-led education

Brexit, Trump and the failure of our universities to pursue wisdom

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 1151

This is the plea of a mother of a two-year-old son with cystic fibrosis, a chronic health condition that makes him particularly vulnerable to respiratory viruses.

Panic-buying and hoarding has major consequences on the weak and vulnerable in our society.

Food banks run out of milk and other staples as shoppers panic-buy

'Some shelves are empty in supermarkets in Sydney after panic buying.'-Photo:news.sky.com

As coronavirus spreads, I am terrified that Australia's fear and greed could cost my son his life*

'Stockpiling essential supplies and ignoring quarantine advice can have deadly consequences for the most vulnerable among us.'

‘In a time of panic, please don’t forget to be kind.

Before you roll your eyes at this worthy statement, know it doesn’t come from a place of virtue. It comes from the mother of Harry, my two-year-old son with cystic fibrosis, a chronic health condition that makes him particularly vulnerable to respiratory viruses.

I write this from a place of deep anxiety, stemming from the familiarity I have with the smells of fear and tears accompanying an intensive care unit in a children’s hospital. A year ago, I watched as my son was sedated and put on oxygen because of complications arising from rhinovirus – the common cold – combined with two other respiratory viruses. I shudder to think what Covid-19 could do to his already compromised lungs.

But I am more worried about the human reaction to the virus in the weeks to come than I am about the actual virus. And the virus is terrifying. I predict we will witness, as we have already started to, the worst of humanity, including people fighting over toilet paper in a supermarket, people hoarding supplies meaning that others miss out, people going to work when they’re sick or letting their kids out of the house when they should be quarantined. Two weeks is a long time to spend at home to limit the spread of the virus, but I am urging people to please abide by the rules, because doing so will protect the vulnerable. Doing so will protect Harry.

Sally Killoran’s son Harry.-Photo: The Guardian

Because of Covid-19’s infancy, we are yet to fully understand how it will affect people with cystic fibrosis, or the many others with compromised immune systems. However, with the death toll rising it is obvious there is cause for serious concern. According to Centers for Disease Control data collated by John Hopkins University, the virus has claimed more than 3400 lives globally, with more than 100,000 cases reported. Reading about the acceleration of cases in Australia in the last week, including the evacuation of Epping Boys High, the words horse and bolted come to mind when talking about containment.

Which is why I am urging you to resist your fear-driven greedy impulses and please remain kind. As our leaders scramble to get ahead of the virus, and amidst media and celebrity-endorsed obfuscation around stockpiling goods, it’s up to us as a nation to control how we personally respond. I ask that you do this with compassion.

As the mother of Harry, I am begging you to think of the flow-on effect your actions have on the vulnerable. Reports of a man who ignored advice to self-quarantine in Hobart yesterday meant he made the inadvertent – but preventable – decision to put many people at risk, and this act may cause the vulnerable to pay the utmost price.

I am asking that on the day you waver over whether or not to send your child into public with flu-like symptoms (fever, sore throat, shortness of breath, cough) please think of Harry, whose life could be limited if this virus takes hold of his already fragile lungs. While this new strain of flu has only been seen to have mild symptoms in children, think of how your child could pass it on to their friend’s father who is fighting cancer, or another friend’s mother with a newborn at home, or a child who regularly visits their elderly grandparents in their nursing home. Think of your child’s friend whose baby sister has spinal muscular atrophy, think of the child in hospital fighting acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, or with another autoimmune disease that Covid-19 could decimate.

I am asking people to be kind, and not to panic in a time when everyone seems scared, because the ridiculous run on toilet paper last week highlighted the fact people are not thinking of others. And while toilet paper isn’t going to save Harry’s life, other goods like hand sanitiser and face masks could help keep him, and his friends with auto-immune problems, safe.

The Department of Health has very clearly said that face masks are not to be used by the healthy. It states: “Masks are not currently recommended for use by healthy members of the public for the prevention of infections like coronavirus. Instead, face masks should be used by people who are experiencing flu-like symptoms so they can protect others from spreading the virus.”

Yet last week I visited at least eight pharmacies and could not buy a face mask for my son to wear when he visits hospital next week for his regular CF clinic. In fact, I have resorted to hassling the kind doctors at the Sydney Children’s Hospital in Randwick to send me face masks so that he can wear them to avoid people coughing on him while he is walking through the hospital. The fact I am wasting the precious time of under-resourced doctors and nurses is appalling, and something I am ashamed of, yet I have been driven to do this because others have hoarded them in case of emergency and I cannot physically buy any in stores.

If we all panic, and are governed by fear-driven greed to take more than we need, who is going to protect the most vulnerable? Yesterday I was dismayed when I saw a social media post from the mum of Harper, who has leukaemia, who couldn’t buy any tissues at her local shop. What has Australia come to when a mum can’t buy tissues for her daughter with leukaemia, on her way home from hospital?

I am asking people, please be kind and don’t take more than what you need. Anyone who enters our house needs to wash their hands with hand sanitiser before they’re welcome, to protect Harry. I know soap and water also do a good job at killing viruses but hand sanitiser is quick and easy and when dealing with children it does the desired job of killing germs, and fast. Yet I can no longer buy hand sanitiser from a shop nearby, and ordering it online will take weeks. Which makes me wonder, where has it all gone? If you have a stockpile at home, please don’t let is gather dust: use it or donate some to your neighbours, because everyone has the same right as you to protect themselves. Now is the time to be using it and buying it, not hoarding it in case you need it later. The crisis is upon us, and it will do no good to hoard supplies for years when we need to use them now.

Last week my husband had an accident and ended up with five stitches in his finger, requiring surgery. I drove around to four different chemists and supermarkets trying to buy him paracetamol. He needed it. In the end, I resorted to asking a woman in the queue in front of me whether she would mind if she gave me one of the five packets of Panadol Rapid she had in her basket, because my husband needed them for pain management that minute. She obliged, and admitted she didn’t actually need Panadol, but they were the only ones left in the store so she thought she should buy them all in case she couldn’t get them again. I get it! It’s a scary time, but if everyone reacts like this, who is going to buy paracetamol for the pensioners when they need it, or for Aunty Beryl who is in chronic pain, or for Harry when he has a fever?

Before you panic, be kind, and think of the vulnerable, and how your actions can affect them.’

*This article by Sally Killoran was first published in The Guardian on 9 March 2020.

...And this was another cry, another plea for KINDNESS...

“In a world where you can be anything, be kind.”

"In a world where you can be anything, be kind," Caroline Flack wrote on Instagram in December 2019.

...And Now Lest We Forget

Why We are Living Through an Epidemic of Selfishness and Greed

Photo:eand.co

The Age of Inhumanity: Selfishness, Competition, Digitalisation, Virtuvalisation and Neoliberalisation, Creating a Zombie World!

The shaming of a bunch of demagogue political, economic and educational leaders that have fooled the world, pushing a SELFISH and Parasitic ideology and philosophy on the world, with tragic outcomes and consequences.

The Damning Impact of a Toxic Philosophy: The Tragedy of Ayn Rand

The Damning Impact of a Toxic Ideology: Neoliberal Legacy of Thatcher and Reagan

The Damning Impact of a Toxic Ideology: Neoliberal Legacy of Koch Brothers

Is Neoliberal Economics and Economists 'The Biggest Fraud Ever Perpetrated on the World?'

Neoliberalism destroys human potential and devastates values-led education

Brexit, Trump and the failure of our universities to pursue wisdom

- “In a world where you can be anything, be kind.”

- Crisis after crisis and the crucial voices of hope

- Is Neoliberal Economics and Economists 'The Biggest Fraud Ever Perpetrated on the World?'

- The Broken Economic Model and the Inhumanity of the Lost Decade of Austerity

- Cortona Week 2020- A Week of Fulfilment, Joy and Friendship