- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 967

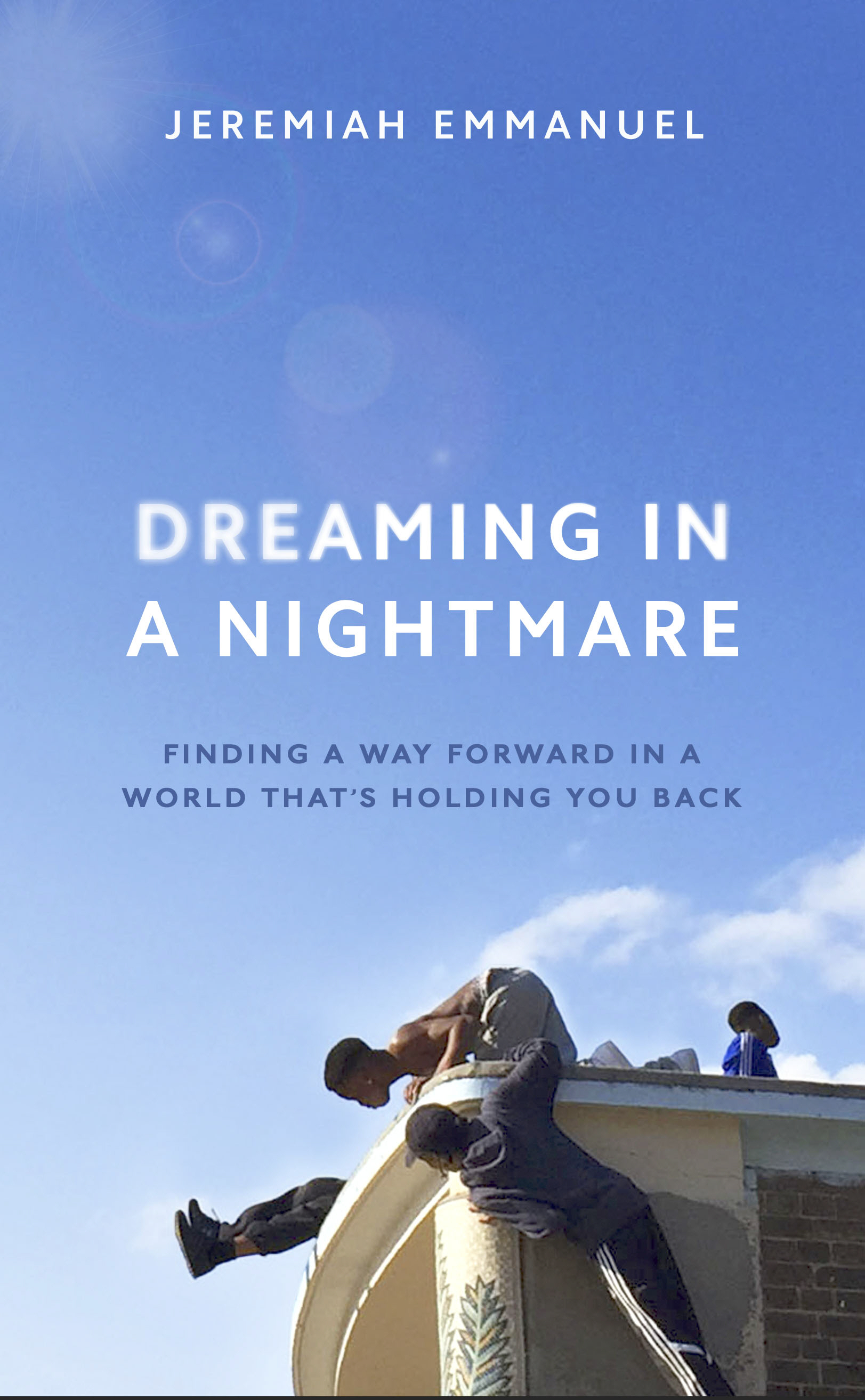

Jeremiah Emmanuel in Conversation and Dialogue with Kieran Yates, The Guardian, on the occasion of the publication of his book: Dreaming in a Nightmare: Finding a Way Forward in a World That’s Holding You Back. *

Jeremiah Emmanuel: 'I hope my book gives people the courage to dream'

'A member of youth parliament at 11, deputy young mayor at 13, Brixton-raised youth activist Jeremiah Emmanuel is now being published by Stormzy'

‘Your definition of success isn’t going to be the same as someone who’s gone to Eton where they’ve been

prepared to be future prime ministers.'-Photo: The Guardian

‘To this day, Jeremiah Emmanuel remembers the first time he caught the 345 bus from Brixton, when he was eight years old. “The last stop said South Kensington – I had never heard of this area before. So I’m looking out the window, and it looks really different. By the time you got to Chelsea, the floor looked the same colour as the day it was paved,” he says, now 21. “I felt like there were so many communities who were so close together and so far away living on parallel lines. Why is there so much inequality in the country?”

The shifts seen out the window of the 345 embody the question at the heart of Emmanuel’s debut book, 'Dreaming in a Nightmare: Finding a Way Forward in a World That’s Holding You Back.' What separated the world at the other end of that bus trip from where it began, next to his favourite haunts: Creams, a dessert cafe where he and his friends would congregate and eat Oreo waffles after, he says, “youth services in Lambeth got decimated”; or the Brixton McDonald’s, also known as “Brikky McD’s”.

For me, it was just the norm. I would hang out in McDonald’s for hours, run over to Lambeth town hall to do my youth politics, then run back to be with my friends again.”

When we meet, we’re near his new home in Vauxhall, just north of Brixton. He proudly holds his book, with his BEM (British Empire Medal), which he received for his services to young people in 2017, on the table in front of him. These are just two of a striking roll call of achievements; a member of the UK Youth Parliament at 11, former deputy young mayor of Lambeth at 13, a former army cadet. He now works with the Gates Foundation and describes himself as a “youth activist and social entrepreneur”.

On the face of it, all this can be seen as a far cry from the trauma in his early life that he describes in the book: being frequently homeless with his mother and siblings until he was seven; being aggressively stopped and searched by police when he was 15 – in the same week as visiting Downing Street to collect an award for his community work; and performing first aid at a house party on a boy who had been stabbed.

“A major way that I got over my trauma was by forgetting,” he says. “My father passed away, being homeless, the brief stint in the care system, when my mum got ill – I lost my memory. It was all just impressions … The writing process brought it back.”

The title, Dreaming in a Nightmare, he is keen to clarify, relates not to Brixton specifically, but to any environment that actively disempowers its citizens. Billed as a memoir, he also calls it a toolkit for empowering young people, to lay out the methods he has used to find success. Like persistence and self-belief, both seen in the email (printed in the book to be used as a practical template) that he sent to the chief executive of Rolls-Royce, aged 17, offering to help the company connect with young people: “Last year, I founded the BBC Radio 1/1Xtra Youth Council … I think Rolls-Royce would benefit from the advice of a similar group.” Rolls-Royce then hired Emmanuel to help it attract more job applicants from young people.

“You can only see what is in front of you,” he says now. “So your definition of success isn’t going to be the same as someone who’s gone to Eton where they’ve been prepared to be a future prime minister or the CEO of Fortune 500 companies. We need to see it.”

While the memoir of a 21-year-old must operate differently from a memoir that comes with more lived experience, reading Dreaming in a Nightmare gives the sense of how bearing the brunt of austerity Britain ages a person. The impact of the 2008-09 recession, the student debt that he was once scared of, the need to work for a charity to plug the gaps of government – all reflect the prospects and challenges facing Gen-Z. Emmanuel includes interviews with his peers to bolster his points, such as Kayla, a close friend and unofficial news broadcaster who will call if there is bad news; or Nathan John-Baptiste, AKA “the Wolf of Walthamstow”, who made more than £25,000 selling snacks from his school toilets back in 2017. Emmanuelwas lacking in his own entrepreneurial approach as a one-time muffin magnate at school. As he humbly acknowledges: “The first business lesson I learned was an important one: never eat your own product.”

Dreaming in a Nightmare was his first foray into professional writing, after the musician Stormzy met Emmanuel through his youth work, and forwarded the manuscript to his Penguin imprint Merky Books. Nine drafts and 12 months later, Emmanuel had a book, written while listening to the soundtrack from his childhood: gospel singers Kirk Franklin and Donnie McClurkin, Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti and Nigerian rapper Burna Boy, as a way to bring him closer to his ancestry.

Writing the book meant sitting down with his mother, Esther, to talk about her life in Nigeria for the first time, he says: “There was a lot I didn’t know, and it was emotional. Like, she was the victim of an armed robbery in Nigeria by people brandishing machetes. When I heard about it, I was angry. For the first time we really connected on a deeper level. So yeah … find out about your family.”

When he quizzes his mother about growing up in Nigeria, he doesn’t dwell on the exoticised abstractions of a mystic land, but takes a very Gen-Z approach to learning about his ancestry, by immediately going to Google Street View to find the exact house on Biaduo Street in Ikoyi, Lagos, where she grew up. It is how a new generation can experience ancestral homelands, bringing these stories of the past into the present in new ways.

Despite new approaches, few things have changed for his generation, still at the mercy of crippling austerity, especially in black, inner-city communities whose members are substantially more likely to be unemployed, live in precarious housing, and be at risk of Covid-19 than their white counterparts. When he repeats old adages, such as “working twice as hard to get half as far”, it is wisdom that could be passed down to any immigrant child in Britain at any time in history.

Emmanuel’s overall position – that we can work with structures like the police and corporate brands – may feel disappointingly safe to some, especially when more and more young people are calling for abolitionist approaches and reimagining new structures, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, or even the recent A-level results debacle, which has amplified fury at UK academic elitism. That is not to say that Emmanuel is without challenge; in one powerful example in the book, he files a complaint to what was then called the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) after a stop and search in Brixton – which then redirected his complaint to Brixton police station. With hindsight, he patiently explains his reaction, and the failures of this system: “The idea behind creating the IPCC was a good one … I have no interest in attacking the police for doing their jobs, but new channels of communication and a new dialogue are desperately needed.”

Though he evades questions directly relating to party politics (“I don’t delve into the political system a lot because of my charitable work”), you get the sense that what Emmanuel is really advocating is to broaden imaginative horizons that are compressed by social deprivation. The fact remains that, for a generation facing unmeasurable challenges, there is immediate work to be done. For Emmanuel, power comes in his ability to look beyond the limitations of a broken world to reimagine a life beyond it. His mission, to empower young people, uses businesses, organisations and projects as examples, with a heady dose of corporate-speak – but he also allows himself the occasional poetic moment. “We all have a dream,” he tells me. “I’m not dreaming all the time but I now know how to do it. I hope the book gives people the courage to do the same.”- *This interview was first published in The Guardian on 20 August 2020

Photo: Penguin Books

A moving and powerful account of the problems faced by a new generation, from crime to poverty to an increasingly divided society, from an extraordinarily accomplished young activist and entrepreneur.

'My name is Jeremiah Emmanuel. I’m twenty years old. I’m an activist, an entrepreneur, a former deputy young mayor of Lambeth and member of the UK Youth Parliament. I wanted to change the world, but the world I was born into changed me first.

Raised in south London, I lived in an area where crime and poverty were everywhere and opportunities to escape were rare. Violence was accepted, prison was expected. Your best friend might vanish overnight, never to be seen again. That was the world I knew; the only one I thought was possible for people like me.

But somehow, as I got older, I found my way to a different world: a place where people listened to you, where opinions were heard, where doors were opened, where there were opportunities around every corner. Everything had stayed the same and everything had changed.

This is the story of how I did it, the people who helped me get there, and the huge hurdles I – and my entire generation – have to learn to face and overcome. It’s the story of how to move forward in a world that’s holding you back.'- Buy the book HERE

A selected readings on similar topics and issues from our archive

The scar on the conscience of Britain: The neglect of its children, youth, students and more

The Broken Economic Model and the Inhumanity of the Lost Decade of Austerity

Austerity driven Homeless children put up in Shipping Containers in ‘Great Britain’

Austerity and its Consequences: No Hope for the Youth

Life, death and economics: Austerity is a killer

Recession, Austerity, Mental, Emotional and Physical Illness

Crisis after crisis and the crucial voices of hope

Is Neoliberal Economics and Economists 'The Biggest Fraud Ever Perpetrated on the World?'

World Transformation and the Youth: Youth to Make the World Great Again

Do you have an eye for justice and sense of duty? Then, these questions are for you.

The Youth of Wales Message of Hope to the World at the Time of the Coronavirus Crisis

GCGI Celebrating Activism and Hope with British VOGUE

In Search of a Better Tomorrow: Reasons for Hope In Times of Uncertainty

This is How to Make the World Great Again: The Compassion Project

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 745

Andrew Marvell 'died of an overdose after spurning Catholic malaria cure'*

Academic finds evidence that Puritan poet took opiate-based remedy

that instead caused him a lethal seizure

Andrew Marvell (1621-1678) was initially believed to have been poisoned by his political enemies.

Photo: The Poetry Foundation

Nota bene

Reading about Andrew Marvell’s fate, reminds me of

Trump and his thoughts on the healing powers of BLEACH to cure COVID-19!!

‘President Donald Trump during an April 23 White House briefing in which he suggested — without evidence —

that both ultraviolet light and disinfectant could be used to treat the coronavirus in humans.’-Caption and photo: Business Insider

And now reverting back to Andrew Marvell and his opiate-based malaria remedy!!

He famously begged his mistress not to be “coy”, warning her: “The grave’s a fine and private place/But none, I think, do there embrace.”

Now new evidence uncovered in a 350-year-old manuscript suggests that Andrew Marvell went to his own grave prematurely, after he accidentally overdosed on an opiate intended to treat his malaria.

Since 1678, the circumstances surrounding the metaphysical poet’s sudden death at the age of 57 have been shrouded in mystery. At the time, there were rumours that the Hull MP, an outspoken Protestant and staunch supporter of Oliver Cromwell, had been poisoned in London by his political or religious enemies.

Nearly 200 years later, a medical account attributing his demise to an attack of malaria was found – and this is the cause of death that has been accepted ever since.

But an academic at the University of Hull has discovered that Marvell had in his possession a handwritten recipe for the remedy mithridate, which suggests the poet was using potentially lethal opiates to treat the fevers caused by his malaria.

The recipe, touted as a remedy “for the plague, fevers, smallpox and surfeits”, is scribbled in a collection of sermons that was formerly assumed to have belonged to Marvell’s father, the Reverend Andrew Marvell, and is held in Hull History Centre. “I noticed that the recipe couldn’t have been from Marvell’s father’s lifetime [Marvell senior died in 1661], because it says it was “made use of” during the great plague [of 1665],” said Dr Stewart Mottram, a senior lecturer in English at Hull. “That threw up a whole series of questions.”

After unearthing evidence that suggested this “very fragile” collection, which includes many of Marvell’s father’s sermons, was actually once owned by Marvell himself, Mottram revisited contemporary accounts of the poet’s death. His paper about his discovery will be published later this year. “People have assumed that Marvell died of malaria because he wasn’t given quinine, a treatment still used today. What I’m suggesting was he died with malaria, because of the drug he took. It was the drug itself – the mithridate – that killed him.”

At the time, opium was a popular painkiller and, as Marvell’s recipe demonstrates, was also viewed as a cure for a wide range of medical problems. “You could take it for anything,” said Mottram. “It had this reputation for being universally beneficial.” It was even perceived as a poison antidote.

Then some doctors began observing that taking mithridate could cause “apoplexies” – strokes – that could be fatal. “And that’s actually what the cause of Marvell’s death was. Literally days after his death, letters were written saying he’d died of an apoplexy.” If Marvell hadn’t overdosed on opium, Mottram believes, he would have survived infection with the strain of malaria that was prevalent in England at the time. It is rarely fatal in human populations. “Malaria was common in 17th-century England, particularly in estuary areas of eastern England like London and Hull. But it was a fairly benign disease.”

Even during Marvell’s lifetime, some English doctors had learned that quinine was a better treatment than mithridate for the fevers caused by malaria. But the drug was viewed with suspicion by Protestants, because it came from South America, which was ruled by Catholic Spain.

“Quinine as a drug was associated with Catholics and Jesuits, and therefore it had a bad reputation in Protestant England,” said Mottram. “If Marvell is known for anything, it’s for his Puritan views and the fact that he supported Oliver Cromwell during the Commonwealth. He’s unlikely to have wanted to take a drug that had a reputation for being something that passed through Catholic hands.”

This prejudice towards mithridate and against quinine may account for the high mortality rates in malarial areas of England at the time. “Marvell offers us a case study, a window into why people who had malaria were dying.”

The fact that Marvell owned a manuscript containing a recipe for mithridate also shines a light on the poet’s wider interests in medicine throughout his life. “There are little-known poems he wrote about disease, including two in Latin about smallpox, and another, also in Latin, which prefaced a translated medical book called Popular Errors in 1651. This book berated the public for doing precisely what Marvell ends up doing – taking too-strong and too-frequent doses of opium. So Marvell writes a poem commending a work that attacks people for overusing opium – then dies from overdosing on opium.”

The English translator of Popular Errors, Robert Witty, was Marvell’s friend and may have been the very doctor who mixed the dose of mithridate that led to his untimely death. “We know that Marvell summoned a doctor, and that Dr Witty, his friend, was with Marvell in Hull in the days before he died.”

Another irony, Mottram points out, is that for nearly two centuries, historians believed Marvell was poisoned. “Actually, what he was poisoned with was a poison antidote.”

*This article by Donna Ferguson was first published in The Observer on 16 August 2020

Read more on similar stories:

Don’t listen to these crackpot coronavirus myths

How Ancient Cure-Alls Paved the Way for Drug Regulation

Mithridates’ Poison Elixir: Fact or Fiction?

Bat soup, dodgy cures and 'diseasology': the spread of coronavirus misinformation

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 952

Sir Paul Nurse FRS, Director, Francis Crick Institute

'Paul Nurse is a geneticist and cell biologist who has worked on how the eukaryotic cell cycle is controlled. His major work has been on the cyclin dependent protein kinases and how they regulate cell reproduction. He is Director of the Francis Crick Institute in London, and has served as President of the Royal Society, Chief Executive of Cancer Research UK and President of Rockefeller University.

He shared the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine and has received the Albert Lasker Award, the Gairdner Award, the Louis Jeantet Prize and the Royal Society's Royal and Copley Medals. He was knighted in 1999, received the Legion d'honneur in 2003 from France, and the Order of the Rising Sun in 2018 from Japan. He served for 15 years on the Council of Science and Technology, advising the Prime Minister and Cabinet, and is presently a Chief Scientific Advisor for the European Union and a trustee of the British Museum'.-Photo: The Francis Crick Institute

Sir Paul in conversation with Andrew Anthony , The Observer*

The Nobel prize-winning scientist on Covid-19, the burden of Brexit, his astonishing upbringing and terrible failures at French

Your book is a reminder of the fundamental importance of cells. Do you think cells have been overshadowed by genes in the public imagination?

I’m a geneticist, so I’ve lived through molecular genetics and molecular biology and that has focused a lot on genes. I do think cells have not caught the attention of the world in perhaps the way they should have done, because it’s the fundamental unit of life. I sometimes use this analogy: it’s like biology’s atom. It’s not the gene, it’s the cell.

During the Covid-19 crisis, you’ve been critical of ministers and advisers, comparing them to blancmange. Do you think we need to rethink that relationship between politicians and advisers?

Yes, I do. I’m particularly concerned about the attempt to convey communication through one-liners such as “we’re following the science”. It’s a sort of populist tendency and that reduces complex situations to an almost meaningless sentence. I also think we need more clarity about how decisions are made. For example, testing for coronavirus was absolutely critical. What they decided to do was produce very big labs to do it, not thinking that this would take many months to get it to work efficiently. Whereas they could have developed it locally and contributed something immediately. All the testing capacity basically did nothing during the big infection phase. That was very bad policy and implemented badly, but we didn’t see the discussions behind those decisions.

Another area of concern for you is the effect of Brexit on the science community. Do you see any cause for optimism there?

Not really. There are three major science blocs in the world, which are North America, China and the far east and Europe. Britain is actually good at science and had a lot of influence in European science. And so we have lost power and influence. That’s a political thing. The psychological thing is that I meet scientific colleagues around the world and they just think that the UK has turned away from collaborative science by looking back on an imperial history that no longer exists. It’s just very sentimental. And we’ve taken a leap several decades into the past.

You mention an extraordinary personal story in the book: that you found out that your sister was actually your mother. How has it affected your sense of identity?

I was in my late 50s when I found out. I was living in New York and I was president of a research university called Rockefeller University. I applied for a green card and was turned down, which was a bit of a surprise because I had a Nobel prize, I was president of a university and I was knighted. It was because they didn’t like my birth certificate, which didn’t name my parents. So I applied for a full birth certificate and discovered the truth. I’m astonished that my parents, who were my grandparents, managed to keep this all quiet. As my actual mother and grandparents were dead, I had no recourse to find out exactly what happened. I would like to know who my father is. I mean, I’m a geneticist. I’m actually quite a good geneticist. And I lived for half a century not knowing my own genetics. I hope I find out before I eventually die.

Your main area of research is in yeast, but you became head of Cancer Research UK. How far away do you think science is from gaining some cellular grip on cancer?

Our understanding of cancer has really dramatically improved. We understand the cellular basis of it, the genetic origins of it, the ways in which it’s caused, the way in which the regulatory circuits get altered in cancer cell tissue, which is immensely complicated and one reason it’s so difficult to develop therapies. Our treatment of it is still lagging but in my view we will be able to get cancer under significantly more control in a matter of decades, though we’ll never be able to eliminate it.

You famously failed your French O-level six times. What are your linguistic skills like these days?

They are absolutely appallingly bad. It’s a matter of great distress to me because I travel a great deal. I even got a Légion d’honneur, believe it or not. I had to give the speech in French! You needed a foreign language to get into university, so they let me sit French six times. I didn’t pass so I worked as a technician for a year. And then eventually I was let into Birmingham University.

What did it mean to you to win the Nobel prize?

The Nobel prize is the prize that everybody knows. I was fortunate that I got it on the 100th anniversary of the Nobel, so it was a great occasion. The fact is that I do talk more to the public and journalists now and it’s mainly because of the Nobel prize. Suddenly you become a public figure. You have to be careful you don’t say anything too stupid. In some countries such as India or China it’s a huge distinction, even in Germany and France. In the UK, we don’t tend to see it like that so much. In some ways, I think that’s a good thing.

- What Is Life? by Sir Paul Nurse is published on 3 September by David Fickling Books (£9.99). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Free UK p&p over £15

* See the original interview HERE

See also: Sir Paul Nurse: 'I looked at my birth certificate. That was not my mother's name'

“What is Life?” with Sir Paul Nurse: Watch the Video

On the 250th Birthday of William Wordsworth Let Nature be our Wisest Teacher

A Sure Path to build a Better World: How nature helps us feel good and do good

- A timeless story: ‘The poet and the world’

- Reflecting on Life: My Childhood in Iran where the love of poetry was instilled in me

- Poetry is the Education that Nourishes the Heart and Nurtures the Soul

- The Emperors with no clothes: The Madness of King Donald- A Modern Day King John

- GCGI Celebrating Activism and Hope with British VOGUE