- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 2800

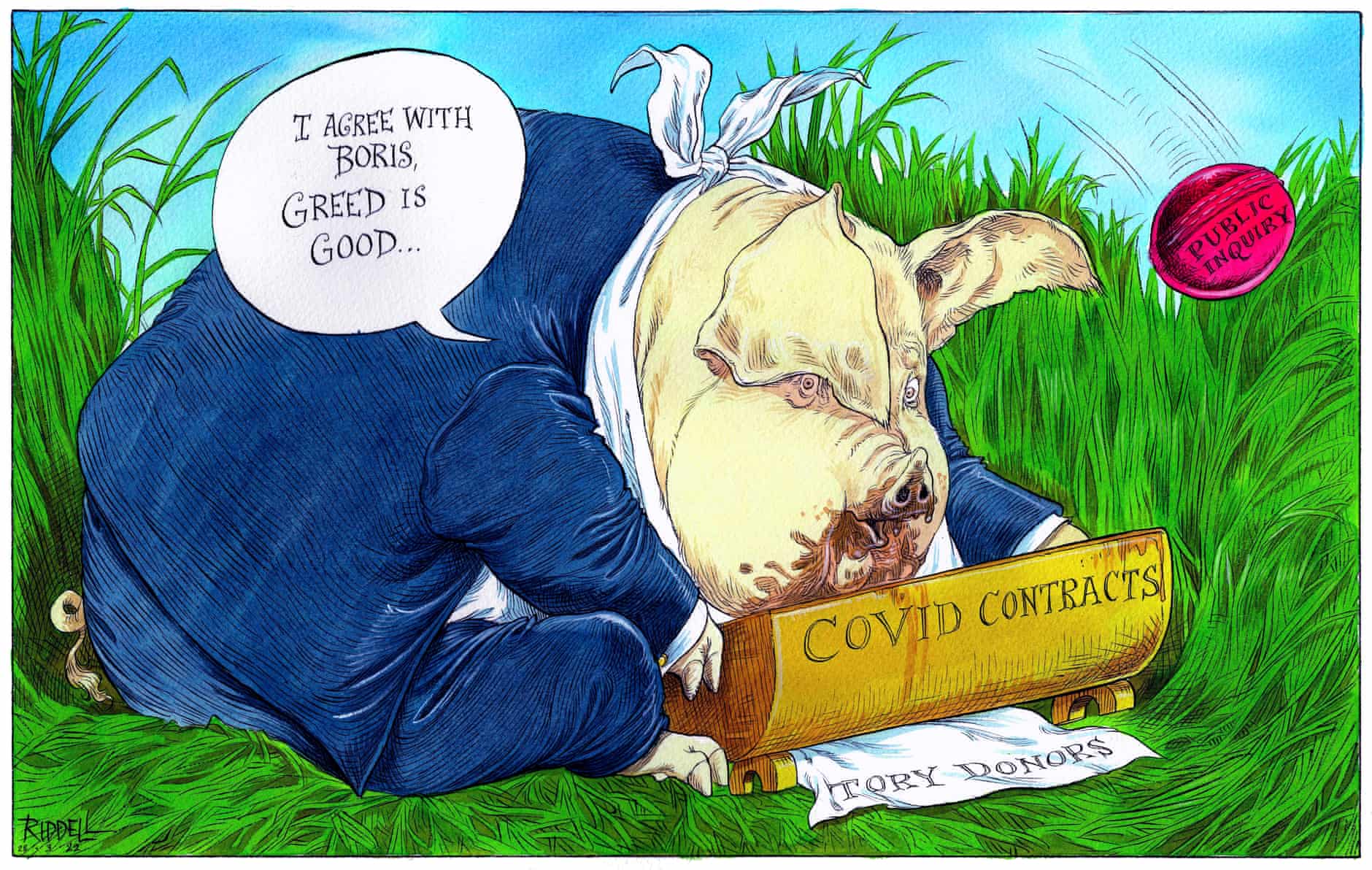

Eton mess and the Rise of Kleptocracy

The people who know the price of everything and value of nothing.

Photo: Peter Macdiarmid/ Getty Images

Paraphrasing the timeless and prophetic words of Socrates, Oh dear Eton Posh Boys why do you care so much about laying up the greatest amount of money and honour and reputation, and so little about wisdom and truth and the greatest improvement of the soul, which you never regard or heed at all? Are you not ashamed of this? For I go about doing nothing else than urging you, young and old, not to care for your persons or your property more than for the perfection of your souls, or even so much; and I tell you that virtue does not come from money, but from virtue comes money and all other good things to man, both the individual and to the state.

‘Part of the English disease is our readiness to ascribe our national disasters to questions of personal character. But the vanities of posh men and their habit of dragging us into catastrophe have much deeper roots. They centre on an ancient system that trains a narrow caste of people to run our affairs, but also ensures they have almost none of the attributes actually required. If this country is to belatedly move into the 21st century, this is what we will finally have to confront: a great tower of failings that, to use a very topical word, are truly institutional.’- John Harris, ‘Britain’s overgrown Eton schoolboys have turned the country into their playground’

‘Boys don’t learn shamelessness at Eton, it is where they perfect it’

Illustration: Chris Riddell/The Guardian

The Posh Boys’ Britain of today and the Collapse of Checks and Balances:

Endless Pursuit of Greed and the disappearance of Moral Compass

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 974

Boris Johnson with Max Hastings in 2002. Photo: Nigel Howard/ANL/Rex Features, via The Guardian

‘The Tory party is about to foist a tasteless joke upon the British people. He cares for nothing but his own fame and gratification’

‘He would not recognise the truth, whether about his private or political life, if confronted by it in an identity parade.’

‘Six years ago, the Cambridge historian Christopher Clark published a study of the outbreak of the first world war, titled The Sleepwalkers. Though Clark is a fine scholar, I was unconvinced by his title, which suggested that the great powers stumbled mindlessly to disaster. On the contrary, the maddest aspect of 1914 was that each belligerent government convinced itself that it was acting rationally.

It would be fanciful to liken the ascent of Boris Johnson to the outbreak of global war, but similar forces are in play. There is room for debate about whether he is a scoundrel or mere rogue, but not much about his moral bankruptcy, rooted in a contempt for truth. Nonetheless, even before the Conservative national membership cheers him in as our prime minister – denied the option of Nigel Farage, whom some polls suggest they would prefer – Tory MPs have thronged to do just that.

I have known Johnson since the 1980s, when I edited the Daily Telegraph and he was our flamboyant Brussels correspondent. I have argued for a decade that, while he is a brilliant entertainer who made a popular maître d’ for London as its mayor, he is unfit for national office, because it seems he cares for no interest save his own fame and gratification.

Tory MPs have launched this country upon an experiment in celebrity government, matching that taking place in Ukraine and the US, and it is unlikely to be derailed by the latest headlines. The Washington Post columnist George Will observes that Donald Trump does what his political base wants “by breaking all the china”. We can’t predict what a Johnson government will do, because its prospective leader has not got around to thinking about this. But his premiership will almost certainly reveal a contempt for rules, precedent, order and stability.

A few admirers assert that, in office, Johnson will reveal an accession of wisdom and responsibility that have hitherto eluded him, not least as foreign secretary. This seems unlikely, as the weekend’s stories emphasised. Dignity still matters in public office, and Johnson will never have it. Yet his graver vice is cowardice, reflected in a willingness to tell any audience, whatever he thinks most likely to please, heedless of the inevitability of its contradiction an hour later.

Like many showy personalities, he is of weak character. I recently suggested to a radio audience that he supposes himself to be Winston Churchill, while in reality being closer to Alan Partridge. Churchill, for all his wit, was a profoundly serious human being. Far from perceiving anything glorious about standing alone in 1940, he knew that all difficult issues must be addressed with allies and partners.

Churchill’s self-obsession was tempered by a huge compassion for humanity, or at least white humanity, which Johnson confines to himself. He has long been considered a bully, prone to making cheap threats. My old friend Christopher Bland, when chairman of the BBC, once described to me how he received an angry phone call from Johnson, denouncing the corporation’s “gross intrusion upon my personal life” for its coverage of one of his love affairs.

“We know plenty about your personal life that you would not like to read in the Spectator,” the then editor of the magazine told the BBC’s chairman, while demanding he order the broadcaster to lay off his own dalliances.

Bland told me he replied: “Boris, think about what you have just said. There is a word for it, and it is not a pretty one.”

He said Johnson blustered into retreat, but in my own files I have handwritten notes from our possible next prime minister, threatening dire consequences in print if I continued to criticise him.

Johnson would not recognise truth, whether about his private or political life, if confronted by it in an identity parade. In a commonplace book the other day, I came across an observation made in 1750 by a contemporary savant, Bishop Berkeley: “It is impossible that a man who is false to his friends and neighbours should be true to the public.” Almost the only people who think Johnson a nice guy are those who do not know him.

There is, of course, a symmetry between himself and Jeremy Corbyn. Corbyn is far more honest, but harbours his own extravagant delusions. He may yet prove to be the only possible Labour leader whom Johnson can defeat in a general election. If the opposition was led by anybody else, the Tories would be deservedly doomed, because we would all vote for it. As it is, the Johnson premiership could survive for three or four years, shambling from one embarrassment and debacle to another, of which Brexit may prove the least.

For many of us, his elevation will signal Britain’s abandonment of any claim to be a serious country. It can be claimed that few people realised what a poor prime minister Theresa May would prove until they saw her in Downing Street. With Boris, however, what you see now is almost assuredly what we shall get from him as ruler of Britain.

We can scarcely strip the emperor’s clothes from a man who has built a career, or at least a lurid love life, out of strutting without them. The weekend stories of his domestic affairs are only an aperitif for his future as Britain’s leader. I have a hunch that Johnson will come to regret securing the prize for which he has struggled so long, because the experience of the premiership will lay bare his absolute unfitness for it.

If the Johnson family had stuck to show business like the Osmonds, Marx Brothers or von Trapp family, the world would be a better place. Yet the Tories, in their terror, have elevated a cavorting charlatan to the steps of Downing Street, and they should expect to pay a full forfeit when voters get the message. If the price of Johnson proves to be Corbyn, blame will rest with the Conservative party, which is about to foist a tasteless joke upon the British people – who will not find it funny for long.’

*Max Hastings is a former editor of the Daily Telegraph and the London Evening Standard

For more information see: A look at the biggest casualty of Boris Johnson’s COVID-19 Britain, without which life becomes meaningless

......

Photo: Financial Times

And then after he got his Brexit done, It only took just 12 months

for Boris Johnson to create a government of sleaze

Boris Johnson the architect of Brexit is the modern-day Enoch Powell

The Most Compelling Story of Boris Johnson’s Madness and his Nonsensical Brexit

Britain Has Become a Sinking Ship of Systemic Corruption, Cronyism and Chumocracy

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 993

Good business isn’t just making money, loads of profit and greed – it’s also about doing good.

There’s a way to it, if we do it for the common good.

Lest We Forget

Why do we need an Economy for the Common Good, and what might it look like?

A Businessman and an Economist in Dialogue for the Common Good

This is How to Balance Purpose and Profit to become a Force for Good

Can Jamie Dimon Make Finance and Banking to Act in the Interest of the Common Good?

In 2020 Jamie Dimon, CEO, JPMorgan Chase

Called for Business and Government to Act in the Interest of the Common Good

Photo:facebook.com

This year, in 2021, he has some big ideas on how to fix America* (see below for more)

A Human Approach to Leadership

‘COVID-19 has proved to be a powerful catalyst for change. Amongst all the tragedy there is a hope that the corporate world will emerge from the dark days of 2020 having learned some fundamental lessons about the human race. Faced with our vulnerability to a silent killer we have had to think about what is important in life.

‘We are living through an exciting and challenging time in the development of leadership. It’s taken a virus to knock us out of our complacency and force us to rethink many assumptions that govern the world of work. COVID-19 has accelerated the rate of social and economic change and leaders cannot afford to be left behind.’- Eric Cornuel, President, EFMD Global

Finance, Banking, Business and the Common Good?*

Photo: The New York Times

‘Many of our citizens are unsettled, and the fault line for all this discord is a fraying American dream – the enormous wealth of our country is accruing to the very few. In other words, the fault line is inequality. And its cause is staring us in the face: our own failure to move beyond our differences and self-interest and act for the greater good. The good news is that this is fixable.’- Jamie Dimon, CEO, JPMorgan Chase, annual letter to shareholders, 7 April 2021

‘Jamie Dimon has a lot to say about how to fix America. In his annual letter to shareholders, the JPMorgan Chase CEO discussed the economic recovery after Covid-19, his thoughts on leadership and the purpose of companies, and US public policy. The document is 66 pages long—three times longer than last year’s letter—and a full 22 pages are devoted to Dimon’s prescriptions for rebuilding America and addressing what he sees as the world’s biggest problems: climate change, poverty, economic development, and racial inequality. It’s a banker’s manifesto for a more progressive form of capitalism, masquerading as a corporate report.

Dimon’s missive followed a week in which dozens of prominent CEOs spoke out with varying degrees of conviction against a new Georgia law limiting voting access in ways that will disproportionately affect Black Americans. Most of these corporate defenses of democracy were brief, belated (many came after the vote and under activist pressure), and carefully lofty. “The right to vote is the essence of a democratic society, and the voice of every voter should be heard,” wrote the Business Roundtable, representing nearly 200 CEOs. That shouldn’t be a controversial point of view, but in America in 2021, it is.

Microsoft president Brad Smith’s approach was more in the Jamie Dimon mould. In a blog post, Smith took on each of the law’s major provisions and urged “the business community to be principled, substantive, and concrete in explaining its concerns.”

When enough corporate leaders band together to oppose legislation, politicians listen. Even the most anodyne statements can have an effect. But CEOs serious about corporate responsibility will have to grapple with the issues in a lot more detail. They’ll need to explain how social and political questions are connected to economic and corporate ones, be clear about their companies’ responsibilities and interests, admit their own complicity, and define the society they want to help build. For that, even 66 pages won’t be enough'. — Excerpts by Katherine Bell, editor in chief, Quartz Daily Brief, 10 April 2021

*Jamie Dimon, CEO, JPMorgan Chase, annual letter to shareholders, 7 April 2021

......

Read more similar articles from the GCGI Archive:

Dear Mr. Johnson, your Covid-19 survival must become a force for good

Responsible Leadership in Action, Geneva, June 2015

Detaching Nature from Economics is ‘Burning the Library of Life’

Good Riddance to Trump: A Disgraced Man who Never Cultivated Goodness and Humanity

Can President Biden Heal and Build a Better America, where Goodness is Valued above Greatness?

This is why every country needs a Jacinda Ardern to discover What it Means to be Human and Great

Ten Steps to Build a World in the Interest of the Common Good

Photo:twitter.com

- Education to Make us Human: What’s Kindness, Love, Compassion, or Beauty Got to Do With Teaching and Education?

- Some of the biggest questions ever asked on Being without Believing

- My poem of the Month: Springing back in April with a Renewed Sense of Hope and Optimism

- Happy Nowruz-Eide Shoma Mobarak: The Joy of Spring and Celebration of our Common Humanity

- Our Heros, the Nasty Party and What it Means to be Human