- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 15718

Photo:pinterest

Those familiar with my writings will easily recall the following passage that I have often written about:

“The idea of an economics which is value-free is totally false. Nothing in life is morally neutral. In the end, economics cannot be separated from a vision of what it is to be a human being in society. In order to arrive at such understanding, my first recommendation is for us to begin a journey to wisdom, by embodying the core values of the Golden Rule (Ethic of Reciprocity): “Do unto others as you would have them to do to you”. This in turn will prompt us on a journey of discovery, giving life to what many consider to be the most consistent moral teaching throughout history. It should be noted that the Golden Rule can be found in many religions, ethical systems, spiritual traditions, indigenous cultures and secular philosophies.”

Now let me explore more and try to share with you more fully the significance and relevance of the Golden Rule tour daily lives. Here I am inspired by the writings of Fr. Harry J. Gensler, SJ, who notes the following:

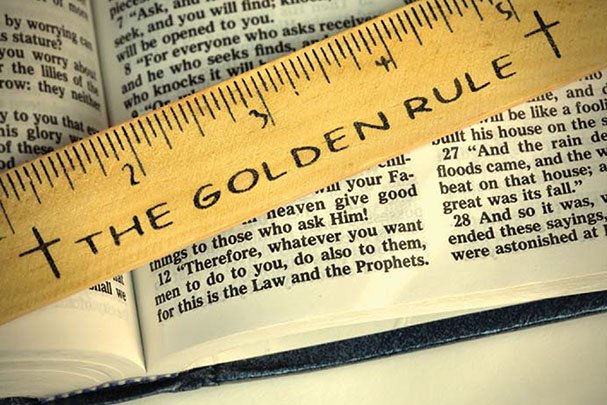

Treat others as you want to be treated

Golden-rule essay

The golden rule is endorsed by all the great world religions; Jesus, Hillel, and Confucius used it to summarize their ethical teachings. And for many centuries the idea has been influential among people of very diverse cultures. These facts suggest that the golden rule may be an important moral truth.

Let's consider an example of how the rule is used. President Kennedy in 1963 appealed to the golden rule in an anti-segregation speech at the time of the first black enrolment at the University of Alabama. He asked whites to consider what it would be like to be treated as second-class citizens because of skin color. Whites were to imagine themselves being black -- and being told that they couldn't vote, or go to the best public schools, or eat at most public restaurants, or sit in the front of the bus. Would whites be content to be treated that way? He was sure that they wouldn't -- and yet this is how they treated others. He said the "heart of the question is ... whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated."

The golden rule is best interpreted as saying: "Treat others only as you consent to being treated in the same situation." To apply it, you'd imagine yourself on the receiving end of the action in the exact place of the other person (which includes having the other person's likes and dislikes). If you act in a given way toward another, and yet are unwilling to be treated that way in the same circumstances, then you violate the rule.

To apply the golden rule adequately, we need knowledge and imagination. We need to know what effect our actions have on the lives of others. And we need to be able to imagine ourselves, vividly and accurately, in the other person's place on the receiving end of the action. With knowledge, imagination, and the golden rule, we can progress far in our moral thinking.

The golden rule is best seen as a consistency principle. It doesn't replace regular moral norms. It isn't an infallible guide on which actions are right or wrong; it doesn't give all the answers. It only prescribes consistency -- that we not have our actions (toward another) be out of harmony with our desires (toward a reversed situation action). It tests our moral coherence. If we violate the golden rule, then we're violating the spirit of fairness and concern that lie at the heart of morality.

The golden rule, with roots in a wide range of world cultures, is well suited to be a standard that different cultures can appeal to in resolving conflicts. As the world becomes more and more a single interacting global community, the need for such a common standard is becoming more urgent.

Golden Rule Chronology

(Based on an excellent study by Fr. Harry J. Gensler, SJ)

1,000,000 BC The fictional Fred Flintstone helps a stranger who was robbed and left to die. He says "I'd want him to help me." Golden rule thinking is born!

c. 1,000,000 BC to 10,000 BC Humans find that cooperative hunting works better. Small, genetically similar clans who use the golden rule to promote cooperation and sharing have a better chance to survive.

c. 1800 BC Egypt's "Eloquent peasant" story has been said to have the earliest known golden-rule saying: "Do to the doer to cause that he do." But the translation is disputed and it takes much stretching to see this as the golden rule. (See my §3.2e.)

c. 1450 BC to 450 BC The Jewish Bible has golden-rule like passages, including: "Don't oppress a foreigner, for you well know how it feels to be a foreigner, since you were foreigners yourselves in the land of Egypt" (Exodus 23:9) and "Love your neighbor as yourself" (Leviticus 19:18).

c. 700 BC In Homer's Odyssey, goddess Calypso tells Odysseus: "I'll be as careful for you as I'd be for myself in like need. I know what is fair and right."

c. 624-546 BC First philosopher Thales, when asked how to live virtuously, reportedly replies (according to the unreliable Diogenes Laertius c. 225 AD): "By never doing ourselves what we blame in others." A similar saying is attributed to Thales's contemporary, Pittacus of Mytilene.

c. 563-483 BC Buddha in India teaches compassion and shunning unhealthy desires. His golden rule says: "There is nothing dearer to man than himself; therefore, as it is the same thing that is dear to you and to others, hurt not others with what pains yourself" (Dhammapada, Northern Canon, 5:18).

c. 551-479 BC Confucius sums up his teaching as: "Don't do to others what you don't want them to do to you." (Analects 15:23)

c. 522 BC Maeandrius of Samos (in Greece), taking over from an evil tyrant, says (according to the historian Herodotus c. 440 BC, in his Histories 3.142): "What I condemn in another I will, if I may, avoid myself." Xerxes of Persia c. 485 BC said something similar (Histories 7.136).

c. 500 BC Jainism, a religion of India that promotes non-violence, compassion, and the sacredness of life, teaches the golden rule: "A monk should treat all beings as he himself would be treated." (Jaina Sutras, Sutrakritanga, bk. 1, 10:1-3)

c. 500 BC Taoist Laozi says: "To those who are good to me, I am good; and to those who are not good to me, I am also good; and thus all get to receive good." (Tao Te Ching 49) A later work says: "Regard your neighbor's gain as your gain and your neighbor's loss as your loss." (T'ai-Shang Kan-Ying P'ien)

c. 500 BC Zoroaster in Persia teaches the golden rule: "That character is best that doesn't do to another what isn't good for itself" and "Don't do to others what isn't good for you."

c. 479-438 BC Mo Tzu in China teaches the golden rule: "Universal love is to regard another's state as one's own. A person of universal love will take care of his friend as he does of himself, and take care of his friend's parents as his own. So when he finds his friend hungry he will feed him, and when he finds him cold he will clothe him." (Book of Mozi, ch. 4)

c. 440 BC Socrates (c. 470-399 BC) and later Plato (c. 428-347 BC) begin the classical era of Greek philosophy. The golden rule, while not prominent in their thinking, sometimes leaves a trace. As Socrates considers whether to escape from jail, he imagines himself in the place of the state, who would be harmed (Crito). And Plato says: "I'd have no one touch my property, if I can help it, or disturb it without consent on my part; if I'm a man of reason, I must treat the property of others the same way" (Laws). (Wattles 1996: 32-6)

c. 436-338 BC Isocrates in Greece teaches the golden rule as promoting self-interest (you do unto others so that they'll do unto you). He says: "Don't do to others what angers you when you experience it from others." The golden rule then becomes common, in positive and negative forms, in Greco-Roman culture, in Sextus, Demosthenes, Xenophon, Cassius Dio, Diogenes Laertius, Ovid, and others. The golden rule has less impact on Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and early Stoics. (Meier 2009: 553f)

c. 400 BC Hinduism has positive and negative golden rules: "One who regards all creatures as his own self, and behaves towards them as towards his own self attains happiness. One should never do to another what one regards as hurtful to one's own self. This, in brief, is the rule of righteousness. In happiness and misery, in the agreeable and the disagreeable, one should judge effects as if they came to one's own self." (Mahabharata bk. 13: Anusasana Parva, §113)

384-322 BC Aristotle says: "As the virtuous man is to himself, he is to his friend also, for his friend is another self" (Nicomachean Ethics 9:9). Diogenes Laertius (c. 225 AD) reports Aristotle as saying that we should behave to our friends as we wish our friends to behave to us.

c. 372-289 BC Mencius, Confucius's follower, says (Works bk. 7, A:4): "Try your best to treat others as you would wish to be treated yourself, and you will find that this is the shortest way to benevolence."

c. 300 BC Sextus the Pythagorean in his Sentences expresses the golden rule positively and negatively: "As you wish your neighbors to treat you, so treat them. What you censure, do not do." (Meier 2009: 554 & 628)

c. 150 BC Various Jewish sources have golden-rule sayings. Tobit 4:16 says "See that you never do to another what you'd hate to have done to yourself." Sirach 31:15 says "Judge the needs of your guest by your own." And the Letter of Aristeas (see Meier 2009: 553f) says "Insofar as you [the king] do not wish evils to come to you, but to partake of every blessing, [it would be wise] if you did this with your subjects."

c. 30 BC to 10 AD Rabbi Hillel, asked to explain the Torah while a Gentile stood on one foot, uses the golden rule: "What is hateful to yourself, don't do to another. That is the whole Torah. The rest is commentary. Go and learn." (Sanhedrin of the Babylonian Talmud 56a)

c. 20 BC to 50 AD Jewish thinker Philo of Alexandria, in speaking of unwritten customs and ordinances, mentions first "Don't do to another what you'd be unwilling to have done to you." (Hypothetica 7:6)

c. 4 BC to 27 AD Jesus proclaims love (of God and neighbor) and the golden rule to be the basis of how to live. Luke 6:31 gives the golden rule in the context of loving your enemies, later illustrated by the Good Samaritan parable. Matthew 7:12 says: "Treat others as you want to be treated, for this sums up the Law and the prophets."

c. 4 BC to 65 AD Roman Stoic Seneca teaches the golden rule: "Let us put ourselves in the place of the man with whom we are angry; we are often unwilling to bear what we would have been willing to inflict," "Let us give in the way we would like to receive - willingly, quickly, and without hesitation," and "Treat your inferiors as you would be treated by your betters." The golden rule fits well the ethics of the Stoics, who propose a natural moral law, accessible to everyone's reason, that directs us to be just and considerate toward everyone. (Wattles 1996: 39f)

c. 56 AD Paul's letter to the Romans 2:1-3 expresses a golden-rule like idea: "We condemn ourselves when we condemn another for doing what we do."

c. 65 AD The western text of the Acts of the Apostles 15:20 & 29 has a negative golden rule: "What you don't want done to yourself, don't do to others."

c. 70 AD "The Two Ways," a Dead Sea Scroll discovered in the 1940s, says: "The way of life is this: First, you shall love the Lord your maker, and secondly, your neighbor as yourself. And whatever you don't want to be done to you, don't do to anyone else." (Wattles 1996: 47)

c. 80 AD The Didache, summarizing early Christian teachings, begins: "There are two paths, one of life and one of death, and a great difference between them. The way of life is this. First, you shall love the God who made you. Second, you shall love your neighbor as yourself. And whatever you wouldn't have done to you, don't do to another."

c. 90 AD The ex-slave Stoic Epictetus writes: "What you shun enduring yourself, don't impose on others. You shun slavery - beware of enslaving others!"

c. 90 AD The apocryphal gospel of Thomas attributes a negative golden rule to Jesus (verse 6): "Don't do what you hate."

c. 120 AD Rabbi Akiba says: "This is the fundamental principle of the Law: Don't treat your neighbor how you hate to be treated yourself." (G. King 1928: 268) His students support the golden rule: Rabbi Eleazar ("Let another's honor be as dear to you as your own") and Rabbi Jose ("Let another's property be as dear to you as your own"). (Wattles 1996: 202)

c. 130 AD Aristides defends his fellow Christians, who "never do to others what they would not wish to happen to themselves," against persecution.

c. 150 AD The Ethiopian version of the apocryphal Book of Thekla ascribes a negative golden rule to Paul: "What you will not that men should do to you, you also shall not do to another."

c. 150-1600 Many Christians, seeing the golden rule's wide acceptance across religions and cultures, view the golden rule as the core of the natural moral law that Paul saw as written on everyone's heart (Romans 2:14f). The golden rule is proclaimed as the central norm of the natural moral law by Justin Martyr, Origen, Basil, Augustine, Gratian, Anselm of Canterbury, William of Champeaux, Peter Lombard, Hugh of St. Victor, John of Salisbury, Bonaventure, Duns Scotus, Luther, Calvin, and Erasmus. (Reiner 1983 and du Roy 2008)

222-235 Roman Emperor Alexander Severus adopts the golden rule as his motto, displays it on public buildings, and promotes peace among religions. Some say the golden rule is called golden because Severus wrote it on his wall in gold.

c. 263-339 Eusebius of Caesarea's golden-rule prayer begins: "May I be an enemy to no one and the friend of what abides eternally. May I never quarrel with those nearest me, and be reconciled quickly if I should. May I never plot evil against others, and if anyone plot evil against me, may I escape unharmed and without the need to hurt anyone else."

349-407 John Chrysostom teaches the golden rule: "Whatever you would that men should do to you, do to them. Let your own will be the law. Do you wish to receive kindness? Be kind to another. And again: Don't do to another what you hate. Do you hate to be insulted? Don't insult another. If we hold fast to these two precepts, we won't need any other instruction." (du Roy 2008: 91)

354-430 Augustine says that the golden rule is part of every nation's wisdom and leads us to love God and neighbor (since we want both to love us). He gives perhaps the first golden-rule objection: if we want bad things done to us (e.g., we want others to get us drunk), by the golden rule we'd have a duty to do these things to others. He in effect suggests taking the golden rule to mean "Whatever good things you want done to yourself, do to others." [Actually, he thought that willing, as opposed to desiring, is always for the good; so he formulated the golden rule in terms of willing.]

610 Muhammad receives the Qur'an, which instructs us to do good to all (4:36) and includes the golden-rule like saying: "Woe to those who cheat: they demand a fair measure from others but they do not give it themselves" (83:1-3). Several Hadiths (Bukhari 1:2:12, Muslim 1:72f, and An-Nawawi 13) attribute this golden rule to Muhammad: "None of you is a true believer unless he wishes for his brother what he wishes for himself."

c. 650 Imam Ali, Muhammad's relative, says: "What you prefer for yourself, prefer for others; what you find objectionable for yourself, treat as such for others. Don't wrong anyone, just as you would not like to be wronged; do good to others just as you would like others to do good to you; that which you consider immoral for others, consider immoral for yourself."

c. 700 Shintoism in Japan expresses the golden rule: "Be charitable to all beings, love is God's representative. Don't forget that the world is one great family. The heart of the person before you is a mirror; see there your own form."

c. 810 The Book of Kells, a gospel book lavishly illustrated by Irish monks, illustrates the golden rule as a dog extending a paw of friendship to a rabbit.

c. 890 King Arthur's Laws emphasizes the golden rule: "What you will that others not do to you, don't do to others. From this one law we can judge rightly."

c. 1060 Confucian philosopher Zhang Zai writes: "If one loves others just as one is disposed to love oneself, one realizes benevolence completely. This is illustrated by the words 'If something is done to you and you don't want it, then for your part don't do it to others.'" (Nivison 1996: 67)

c. 1093 Muslim Abu Hamid al-Ghazali in his Disciplining the Soul (the section on discovering faults) uses the golden rule: "Were all people only to renounce the things they dislike in others, they would not need anyone to discipline them."

1140 Gratian, the father of canon law, identifies natural law with the golden rule: "By natural law, each person is commanded to do to others what he wants done to himself and is prohibited from inflicting on others what he does not want done to himself. Natural law is common to all nations because it exists everywhere by natural instinct. It began with the appearance of rational creatures and does not change over time, but remains immutable." (Pennington 2008)

c. 1170 Moses Maimonides's Sefer Hamitzvoth (positive commandment 208) says: "Whatever I wish for myself, I am to wish for another; and whatever I do not wish for myself or for my friends, I am not to wish for another. This injunction is contained in His words: 'Love your neighbor as yourself.'"

c. 1200 Inca leader Manco Cápac in Peru teaches: "Each one should do unto others as he would have others do unto him." (Wattles 1996: 192)

c. 1200 The Tales of Sendebar, a popular romance in many languages, ends with words from the sage Sendebar to a king of India: "'My request is that you don't do to your neighbor what is hateful to you and that you love your neighbor as yourself.' The King did as Sendebar counseled him and was wiser than all the sages of India." (Epstein 1967: 297-9)

c. 1220 Francis of Assisi, who often invokes the golden rule, at least four times formulates it using a same-situation clause (the earliest such use that I'm aware of), as in "Blessed is the person who supports his neighbor in his weakness as he would want to be supported were he in a similar situation."

c. 1230 Muslim Sufi thinker Ibn Arabi sees the golden rule as applying to all creatures: "All the commandments are summed up in this, that whatever you would like the True One to do to you, that do to His creatures." (See my §3.1c.)

1259 Gulistan, by the Persian poet Sa'di, has these verses, which are now displayed at the entrance of the United Nations Hall of Nations: "Human beings are members of a whole, In creation of one essence and soul. If one member is afflicted with pain, Other members uneasy will remain. If you have no sympathy for human pain, The name of human you cannot retain."

1265-74 Thomas Aquinas's Summa Theologica (I-II, q. 94, a. 4) says the golden rule is common to the gospels and to human reason. He adds (I-II, q. 99, a. 1) that "when it is said, 'All things whatsoever you would that men should do to you, do you also to them,' this is an explanation of the rule of neighborly love contained implicitly in the words, 'You shall love your neighbor as yourself.'"

c. 1400 Hindu Songs of Kabir (65) teach the golden rule: "One who is kind and who practices righteousness, who considers all creatures on earth as his own self, attains the Immortal Being; the true God is ever with him."

c. 1400 Sikhism from India teaches: "Conquer your egotism. As you regard yourself, regard others as well." (Shri Guru Granth Sahib, Raag Aasaa 8:134)

1477 Earl Rivers's Dictes and Sayings of the Philosophers, the first book printed in England, has (p. 70): "Do to other as thou wouldst they should do to thee. And do to noon other but as thou wouldst be doon to."

NOTE: Http://eebo.chadwyck.com has Rivers's book and almost every book published in English from 1477 to 1700, including the British books mentioned here.

c. 1532 Martin Luther's commentary on the Sermon on the Mount says of the golden rule: "With these words Jesus now concludes his teaching, as if he said: 'Would you like to know what I have preached, and what Moses and all the prophets teach you? Then I will tell you in a very few words.' There is surely no one who would like to be robbed. Why don't you then conclude that you shouldn't rob another? See, there is your heart that tells you truly how you would like to be treated, and your conscience that concludes that you should also do thus to others." (Raunio 2001 is a whole book on the golden rule in Luther.)

1553 The Anglican Book of Common Prayer's catechism says: "What is your duty towards your neighbor? Answer: My duty towards my neighbor is, to love him as myself. And to do to all men as I would they should do unto me."

1558 John Calvin's commentary on Matthew, Mark, and Luke says: "Where our own advantage is concerned, there is not one of us who cannot explain minutely and ingeniously what ought to be done. Christ therefore shows that every man may be a rule of acting properly and justly towards his neighbors, if he do to others what he requires to be done to him."

1568 Humfrey Baker uses the term "golden rule" of the mathematical rule of three: if a/b = c/x then x = (b × c)/a. At this time, "golden rule" isn't yet applied to "Do unto others" but rather is used for key principles of any field. Many British writers of this time speak of "Do unto others" but don't call it the "golden rule" (these writers include John Ponet in 1554, Giovanni Battista Gelli in 1558, William Painter in 1567, Laurence Vaux in 1568, John Calvin in 1574, Everard Digby in 1590, and Olivier de La Marcha in 1592).

1568 Laurence Vaux's Catechism says that the last seven commandments are summed up in "Do unto others, as we would be done to ourselves."

1599 Edward Topsell writes that "Do unto others" serves well instead of other things that have been called golden rules.

1604 Charles Gibbon is perhaps the first author to explicitly call "Do unto others" the golden rule. At least 10 additional British authors before 1650 use golden rule to refer to "Do unto others": William Perkins in 1606, Thomas Taylor in 1612 & 1631, Robert Sanderson in 1627, John Mayo in 1630, Thomas Nash in 1633, John Clark in 1634, Simeon Ashe in 1643, John Ball in 1644, John Vicars in 1646, and Richard Farrar in 1648.

1616 Richard Eburne's The Royal Law discusses the golden rule. Several other writers called the golden rule the royal law (after James 2:8), but this usage didn't catch on.

1644 Rembrandt's Good Samaritan drawing depicts a golden-rule example.

1651 Thomas Hobbes sees humans as naturally egoistic and amoral. Morality comes from a social contract that humans, to further their interests and prevent social chaos, agree to. The golden rule sums up morality: "When you doubt the rightness of your action toward another, suppose yourself in the other's place. Then, when your self-love that weighs down one side of the scale be taken to the other side, it will be easy to see which way the balance turns." (Leviathan, ch. 15)

1660 Robert Sharrock attacks Hobbes and raises golden-rule objections, including the criminal example. (De Officiis secundum Naturae Jus, ch. 2, §11)

1671 Benjamin Camfield publishes a golden-rule book (A Profitable Enquiry Into That Comprehensive Rule of Righteousness, Do As You Would Be Done By) and uses a same-situation clause (p. 61): "We must suppose other men in our condition, rank, and place, and ourselves in theirs." Later golden-rule books by Boraston, Goodman, and Clarke use similar clauses.

1672 Samuel Pufendorf's On the Law of Nature and Nations (bk. 2, 3:13) sees the golden rule as implanted into our reason by God, answers Sharrock's objections, defends the golden rule by the idea that we ought to hold everyone equal to ourselves, and gives golden-rule quotes from various sources (including Hobbes, Aristotle, Seneca, Confucius, and the Peruvian Manco Cápac).

1677 Baruch Spinoza's Ethics (pt. 4, prop. 37) states: "The good which a virtuous person aims at for himself he will also desire for the rest of mankind."

1684 George Boraston publishes a short golden-rule book: The Royal Law, or the Golden Rule of Justice and Charity. He says (p. 4): "Our own regular and well-governed desires, what we are willing that other men should do, or not do to us, are a sufficient direction and admonition, what we in the like cases, ought to do or not to do to them."

1688 John Goodman publishes a golden-rule book: The Golden Rule, Or The Royal Law of Equity Explained. He sees the golden rule as universal across the globe, deals with objections, and puts the golden rule in a Christian context. The golden rule requires "That I both do, or refrain from doing (respectively) toward him, all that which (turning the tables and then consulting my own heart and conscience) I should think that neighbor of mine bound to do, or to refrain from doing toward me in the like case."

1688 Four Pennsylvania Quakers sign the first public protest against slavery in the American colonies, basing this on the golden rule: "There is a saying, that we shall do unto others as we would have them do unto us - making no difference in generation, descent, or color. What in the world would be worse to do to us, than to have men steal us away and sell us for slaves to strange countries, separating us from our wives and children? This is not doing to others as we would be done by; therefore we are against this slave traffic."

1690 John Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding contends that the human mind started as a blank slate and thus the golden rule can't be innate or self-evident (bk. 1, ch. 2, §4): "Should that most unshaken rule of morality, 'That one should do as he would be done unto,' be proposed to one who never heard of it, might he not without absurdity ask why? And then aren't we bound to give a reason? This plainly shows it not to be innate." (We can give a why for the golden rule - see my §§1.8 & 2.1d and ch. 12-13. But what is Locke's "No belief that can be questioned is innate or self-evident" premise based on? Is it innate or self-evident, or how is it proved?)

1693 Quaker George Keith, in an influential pamphlet, gives the first anti-slavery publication in the American colonies. He writes: "Christ commanded, All things whatsoever you would that men should do unto you, do you even so to them. Therefore as we and our children would not be kept in perpetual bondage and slavery against our consent, neither should we keep others in perpetual bondage and slavery against their consent."

1698 Quaker Robert Piles writes: "Some time ago, I was inclined to buy Negroes to help my family (which includes some small children). But there arose a question in me about the lawfulness of this under the gospel command of Christ Jesus: Do unto all men as you would have all men do unto you. We ourselves would not willingly be lifelong slaves."

1704 Gottfried Leibniz raises objection 12 (in my §14.3d), that the golden rule assumes antecedent moral norms: "The rule that we should do to others only what we are willing that they do to us requires not only proof but also elucidation. We would wish for more than our share if we had our way; so do we also owe to others more than their share? I will be told that the rule applies only to a just will. But then the rule, far from serving as a standard, will need a standard."

1706 Samuel Clarke's Discourse Concerning the Unchangeable Obligations of Natural Religion proposes: "Whatever I judge reasonable or unreasonable, for another to do for me, that, by the same judgment, I declare reasonable or unreasonable that I in the like case should do for him. And to deny this either in word or action, is as if a man should contend, that though two and three are equal to five, yet three and two are not so."

1715 John Hepburn's American Defense of the Golden Rule says: "Doing to others as we would not be done by is unlawful. But making slaves of Negroes is doing to others as we would not be done by. Therefore, making slaves of Negroes is unlawful."

1725 Jabez Fitch's "Sermon on the golden rule" defends the golden rule against objections and bases it on Christ's authority, abstract justice, and self-interest.

1739 David Hume's A Treatise of Human Nature, disputing those who see humans as essentially egoistic, argues that sympathy is the powerful source of morality (bk. 3, pt. 2, §1): "There is no human whose happiness or misery does not affect us when brought near to us and represented in lively colors."

1741 Isaac Watts's Improvement of the Mind, in discussing key principles in various fields, says: "Such is that golden principle of morality, which our blessed Lord has given us, Do that to others, which you think just and reasonable that others should do to you, which is almost sufficient in itself to solve all cases of conscience which relate to our neighbor."

1747 Methodism founder John Wesley says that the golden rule "commends itself, as soon as heard, to every man's conscience and understanding; no man can knowingly offend against it without carrying his condemnation in his own breast." (Sermon 30, on Mathew 7:1-12)

1754 John Wollman protests slavery on the basis of the golden rule: "Jesus has laid down the best criterion by which mankind ought to judge of their own conduct: Whatsoever you would that men should do unto you, do you even so to them. One man ought not to look upon another man, or society of men, as so far beneath him, but he should put himself in their place, in all his actions towards them, and bring all to this test: How should I approve of this conduct, were I in their circumstance and they in mine?"

1762 Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Émile (bk. 4) says: "The precept of doing unto others as we would have them do unto us has no foundation other than conscience and sentiment. When an expansive soul makes me identify myself with my fellow, and I feel that I am, so to speak, in him, it is in order not to suffer that I do not want him to suffer. I am interested in him for love of myself, and nature leads me to desire my well-being wherever I feel my existence."

1763 Voltaire, inspired by Confucian writings that Jesuits brought from China, says: "The single fundamental and immutable law for men is the following: 'Treat others as you would be treated.' This law is from nature itself: it cannot be torn from the heart of man." (du Roy 2008: 94)

1774 Caesar Sarter, a black ex-slave, writes: "Let that excellent rule given by our Savior, to do to others, as you would that they should do to you, have its due weight. Suppose that you were ensnared away - the husband from the dear wife of his bosom - or children from their fond parents. Suppose you were thus ravished from such a blissful situation, and plunged into miserable slavery, in a distant land. Now, are you willing that all this should befall you?"

1776 Humphrey Primatt's On the Duty of Mercy and Sin of Cruelty to Brute Animals uses the golden rule: "Do you that are a man so treat your horse, as you would be willing to be treated by your master, in case you were a horse."

1776 Thomas Jefferson writes the Declaration of Independence: "We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." But he owns hundreds of slaves. The poet Phillis Wheatley, a black ex-slave, complains about the inconsistency between American words and actions about freedom.

1777 New England Primer for children has this poem: "Be you to others kind and true, As you'd have others be to you; And neither do nor say to men, Whate'er you would not take again." Some added a retaliatory second verse: "But if men do and say to you, That which is neither kind nor true, Take a good stick, and say to men, 'Don't say or do that same again.'"

1785 Immanuel Kant's Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals has a footnote objecting to the "trivial" golden rule, that it doesn't cover duties to oneself or benevolence to others (since many would agree not to be helped by others if they could be excused from helping others) and would force a judge not to punish a criminal. Kant's objections (which I answer in §14.3c) lowered the golden rule's credibility for many. Yet Kant's larger ethical framework is golden-rule like. His "I ought never to act except in such a way that I can also will that my maxim should become a universal law" resembles Gold 7 of my §2.3. And his "Treat others as ends in themselves and not just as means" is perhaps well analyzed as "Treat others only as you're willing to be treated in the same situation."

1788 John Newton's Thoughts upon the African Slave Trade begins with the golden rule and condemns the trade. A former slave trader, Newton during a storm at sea converted to Christianity. He wrote the Amazing Grace hymn, which begins "Amazing grace, how sweet the sound, that saved a wretch like me!"

1791-1855 Liu Pao-nan's Textual Exegesis of Confucius's Analects says: "Don't do to others what you don't want them to do to you. Then by necessity we must do to others what we want them to do to us." (W. Chan 1955: 300)

1800s The Underground Railroad is a secret network of Americans who help black slaves escape into Canada. To raise funds, they sell anti-slavery tokens, imprinted with things like the golden rule or a crouching slave with the words "Am I not a man and a brother."

1812 The Grimm Brothers' "The old man and his grandson" tells how a grandson reminds his parents to follow the golden rule toward Grandpa (§§1.1 & 6.3).

1817-92 Bahá'u'lláh in Persia establishes the Bahá'í faith, which believes in one God and ultimately just one religion. God revealed himself through prophets that include Abraham, Moses, Krishna, Buddha, Zoroaster, Christ, Muhammad, and Bahá'u'lláh. Humanity is one family and needs to live together in love and fellowship. The Bahá'í golden rule says: "One should wish for one's brother that which one wishes for oneself."

1818 Sir Walter Scott's Rob Roy novel says: "'Francis understands the principle of all moral accounting, the great ethic rule of three. Let A do to B, as he would have B do to him; the product will give the conduct required.' My father smiled at this reduction of the golden rule to arithmetical form."

1818 The Presbyterian General Assembly uses the golden rule to condemn slavery.

1826 Joseph Butler, in a sermon on self-deceit, says: "Substitute another for yourself, consider yourself as the person affected by such a behavior, or toward whom such an action is done: and then you would not only see, but likewise feel, the reasonableness or unreasonableness of such an action."

1827 Joseph Smith receives the Book of Mormon, which has the golden rule: "Therefore, all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them, for this is the law and the prophets" (3 Nephi 14:12).

1828 The Methodist Christian Advocate uses the golden rule to protest America's treatment of Indians.

1836 Angelina Grimké's Appeal to the Christian Women of the South asks: "Are you willing to enslave your children? You start back with horror at such a question. But why, if slavery is no wrong to those upon whom it is imposed? Why if, as has often been said, slaves are happier than their masters, free from the cares of providing for themselves? Do you not perceive that as soon as this golden rule of action is applied to yourselves that you shrink from the test?"

1840 Arthur Schopenhauer's On the Basis of Morality puts compassion at the center: an action has moral worth just if its ultimate motive is the happiness or misery of another (and not our own). Here I directly desire the happiness (or misery-avoidance) of another as if it were my one.

1841 Sarah Griffin's Familiar Tales for Children has a poem: "To do to others as I would, That they should do to me, Will make me gentle, kind, and good, As children ought to be." Some add: "The golden rule, the golden rule, Ah, that's the rule for me, To do to others as I wish, That they should do to me."

1850 Rev. James Thornwell criticizes anti-slavery arguments by attacking the golden rule, using Kant's 1785 criminal example.

1850 President Millard Fillmore, in his State of the Union Address, says: "The great law of morality ought to have a national as well as a personal and individual application. We should act toward other nations as we wish them to act toward us, and justice and conscience should form the rule of conduct."

1851 Mormon Brigham Young, asked about law in Utah, says: "We have a common law which is written upon the tablets of the heart; one of its golden precepts is 'Do unto others as you would they should do unto you.'"

1852 Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin explains slave life and gets people to imagine themselves in slave shoes. One episode features two ministers. One quotes "Cursed be Canaan" from the Bible and explains that God intends Africans to be kept in low condition as servants. A second repeats the golden rule. As a slave "John, aged thirty" is separated from his wife and dragged off the boat with much sorrow, the second minister tells a slave trader: "How dare you carry on a trade like this? Look at these poor creatures!" Stowe's novel became, after the Bible, the best-selling book of the 19th century.

1853 Abraham Lincoln appeals to consistency: "You say A is white and B black, and so A can enslave B. It is color, then, the lighter having the right to enslave the darker? By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet with a fairer skin than yours. You do not mean color exactly? You mean whites are intellectually superior to blacks, and therefore have the right to enslave them? By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet with an intellect superior to yours."

1854 Charles Dickens's Hard Times novel protests poverty caused by greed. Sissy Jupe, asked to give political economy's first principle, is scolded for her answer, "To do unto others as I would that they should do unto me."

1854 Abraham Lincoln quips: "Although volume upon volume is written to prove slavery a very good thing, we never hear of the man who wishes to take the good of it, by being a slave himself."

1855 Frederick Douglass, a black ex-slave, writes: "I love the religion of our blessed Savior. I love that religion that is based upon the glorious principle, of love to God and love to man; which makes its followers do unto others as they themselves would be done by. If you demand liberty to yourself, it says, grant it to your neighbors. If you claim a right to think for yourself, allow your neighbors the same right. It is because I love this religion that I hate the slaveholding, the woman-whipping, the mind-darkening, the soul-destroying religion that exists in the southern states of America."

1858 Abraham Lincoln gives this golden-rule evaluation of slavery: "As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master." The next year, he says: "He who would be no slave, must consent to have no slave."

1860 Rev. John Dagg defends slavery. He says blacks are incapable of exercising civil liberty (so being freed would hurt them), masters ought to care for their slaves (but their occasional cruelty doesn't show that slavery is wrong), the Bible by not condemning slavery implicitly teaches that it's permissible, and the abolitionist the golden rule is flawed (using Kant's 1785 criminal example). (My §8.5 has a rebuttal.)

1861 John Stuart Mill's Utilitarianism argues that our duty is to do whatever maximizes the sum-total of everyone's good (measured by pleasure and pain). He states: "In the golden rule of Jesus, we read the complete spirit of the ethics of utility. To do as you would be done by, and to love your neighbor as yourself, constitute the ideal perfection of utilitarian morality."

1865 Abraham Lincoln quips: "I have always thought that all men should be free; but if any should be slaves, it should be first those who desire it for themselves, and secondly, those who desire it for others. When I hear anyone arguing for slavery, I feel a strong impulse to see it tried on him personally."

1867 Matilda Mackarness's The Golden Rule: Stories Illustrative of the Ten Commandments helps British children learn right from wrong. This was published by Routledge, as is this present book.

1867 Rev. Robert Dabney uses Kant's 1785 criminal example to ridicule the abolitionist use of the golden rule to condemn slavery.

1870 Felix Adler's "The freedom of ethical fellowship" says the golden rule "may be defended on various grounds. The egoist may advise us so to act on grounds of enlightened self-interest. The universalist may exhort us to carry out the rule in the interest of the general happiness. The evolutionist may recommend it as the indispensable condition of social order and progress. The Kantian may enforce it because it bears the test of universality and necessity. The follower of Schopenhauer may concur on grounds of sympathy. Is it not evident that the rule itself is more certain than any of the principles from which it may be deduced? With respect to them, men have differed and will differ. With respect to the rule itself, there is practical unanimity."

1871 Charles Darwin's Descent of Man talks about ethics and evolution. He argues that animals with social instincts naturally develop a moral sense as their intellectual powers develop. Human morality evolves from a limited tribal concern to a higher, universal concern that's summed up in the golden rule.

1874 David Swing's Truths for Today says: "The golden rule underlies our public and private justice, our society, our charity, our education, our religion; and the sorrows of bad government, of famine, of war, of caste, of slavery, have come from contempt of this principle."

1874 Henry Sidgwick's Methods of Ethics says: "The golden rule, 'Do to others as you would have them do to you,' is imprecise in statement; for one might wish for another's co-operation in sin. Nor is it true to say that we ought to do to others only what we think it right for them to do to us; for there may be differences in circumstances which make it wrong for A to treat B in the way it is right for B to treat A. The rule strictly stated must take some form as this: 'It cannot be right for A to treat B in a manner in which it would be wrong for B to treat A, unless we can find reasonable ground for difference of treatment.' Such a principle does not give complete guidance; but its truth is self-evident and common sense has recognized its practical importance." (My §2.1b sees this proposed rule as impartiality, not as the golden rule.)

1879 McGuffey's Fourth Eclectic Reader has a story about a little girl Susan who learns the golden rule from her mother and then returns money she was given by mistake. McGuffey Readers were widely used in American grade schools, had a high golden-rule moral content, and sold 120 million copies between 1836 and 1960.

1885 Mary Baker Eddy's Science and Health puts the golden rule as one of six tenets of Christian Science, which she founded: "We promise to watch and pray for that mind to be in us which was also in Christ Jesus; to do unto others as we would have them do unto us; and to be merciful, just, and pure."

1886 Josiah Royce's Religious Aspects of Philosophy suggests (my paraphrase): Treat others as if you were both yourself and the other, with the experiences of both included in one life.

NOTE: I here begin to paraphrase central ideas of several moral thinkers in golden-rule like ways. I thus emphasize a common theme, but without denying wide disagreements on other points.

1886 Friedrich Nietzsche's Beyond Good and Evil despises "Love your neighbor" as suited only for slaves; he praises the will to power and domination. Exploiting others and dominating the weak is part of our nature; compassion frustrates how we're built. (Nietzsche is the philosopher whose ideas most oppose the golden rule; ch. 7 on egoism discusses his objections.)

1893 The first Parliament of the World's Religions, which meets with the Chicago World's Fair, is the first formal, global meeting of the religions of the world. The golden rule is prominent. (Wattles 1996: 91f)

1897 Edward Bellamy's Equality novel describes the utopian 21st-century Republic of the Golden Rule, characterized by love toward all.

1897-1904 Samuel "Golden Rule" Jones is mayor of Toledo, Ohio and tries to run the city on golden-rule terms. He had run an oil company on the golden rule. His workers were paid fairly, worked hard, and felt like they shared a common enterprise. When he had trouble with workers, he'd try to understand their situation, imagine himself in their place, and then decide what to do using the golden rule. Jones put the golden rule as: "Do unto others as if you were the others."

1898 Mark Twain, a critic of discrimination, in "Concerning the Jews" writes: "What has become of the golden rule? It exists, it continues to sparkle, and is well taken care of. It is Exhibit A in the Church's assets, and we pull it out every Sunday and give it an airing. It has never intruded into business; and Jewish persecution is not a religious passion, it is a business passion."

1899 American poet Edwin Markham in "The Man With the Hoe" describes a poor man who was crushed by the greed of others. When asked how to deal with this problem, he answers: "I have but one solution - that is the application of the golden rule. We have committed the golden rule to heart; now let us commit it to life." (Jones 1899: 194, 397)

c. 1900? From the Yoruba people in Nigeria comes this golden rule: "One who is going to take a pointed stick to pinch a baby bird should first try it on himself to feel how it hurts."

1900 Wu Ting-Fang, a diplomat from China to the U.S., writes an open letter about how both countries need to be fair and honest in cooperating for mutual economic advantage. He appeals to the golden rule, which he sees as part of his Confucian tradition and as the basis for morality.

1902 J.C. Penney in Kemmerer, Wyoming opens the Golden Rule Store, so called (http://www.jcpenney.net/about-us.aspx) because he founded his company on the idea of treating customers the way he wanted to be treated. In 1950, he published a book called Fifty Years with the Golden Rule.

1903 Jack London's People of the Abyss novel denounces urban poverty: "The golden rule determines that East London is an unfit place to live. Where you would not have your own babe live is not a fit place for the babes of other men. It is a simple thing, this golden rule. What is not good enough for you is not good enough for other men."

1903 George Bernard Shaw quips against the literal golden rule: "Do not do unto others as you would that they should do unto you. Their tastes may not be the same." He adds: "The golden rule is that there are no golden rules."

1905 Helen Thompson's "Ethics in private practice" applies the golden rule to nursing: "Would you be in sympathy with your patient? Would you win her confidence? Then regard this poor sufferer in the light of someone dear to you; put her in that other's stead. Someone has said, 'In ethics, you cannot better the golden rule.' Suppose you render it, 'Do unto others as you would they should do unto yours.' This is your mother; this your sister; this your child."

1906 Edward Westermarck's Origin and Development of the Moral Ideas emphasizes moral diversity but claims that all nations agree on the golden rule.

1907 The School Days song mentions the golden rule in the curriculum: "School days, school days, Dear old golden rule days, Readin' and 'ritin' and 'rithmetic, Taught to the tune of the hickory stick."

1908 John Dewey's Ethics suggests (my paraphrase): Treat others in a way that considers their needs on the same basis as your own.

1911 The first Boy Scout Handbook has this quote from Theodore Roosevelt: "No man is a good citizen unless he so acts as to show that he actually uses the Ten Commandments and translates the golden rule into his life conduct."

1912 Arthur Cadoux's "The implications of the golden rule," besides defending the golden rule from Kant's criticisms, argues that the golden rule seeks the fullness of individual and communal life through harmonizing desires.

1914 Mason leader Joseph Newton ends The Builders by saying: "High above all dogmas that divide, all bigotries that blind, will be written the simple words of the one eternal religion - the Fatherhood of God, the brotherhood of man, the moral law, the golden rule, and the hope of a life everlasting!"

1915-8 The Golden Rule Books, based on a U.S. series with the same name, are published to help teach morality to public-school students in Ontario.

1916 C.D. Broad's "False hypotheses in ethics" says: "Suppose Smith were in my circumstances and did the action I propose to do, what should I think of that? If we strongly condemn it, we may be fairly sure that our proposed action is wrong and that our tendency to approve it is due to personal prejudice."

1920 Francis Walters's Principles of Health Control suggests: "As we want others to protect us from their germs, so we should protect them from ours."

1920 W.E.B. du Bois's Darkwater protests America's treatment of blacks: "How could America condemn in Germany that which she commits within her own borders? A true and worthy ideal frees and uplifts a people; a false ideal imprisons and lowers. Say to men, earnestly and repeatedly: 'Honesty is best, knowledge is power; do unto others as you would be done by.' Say this and act it and the nation must move toward it. But say to a people: 'The one virtue is to be white,' and the people rush to the conclusion, 'Kill the n*****!'"

1921 President Warren Harding's inauguration speech says: "I would rejoice to acclaim the era of the golden rule and crown it with the autocracy of service." But scandals plague his administration.

1922 Hazrat Khan's "Ten Sufi Thoughts" says "Although different religions, in teaching man to act harmoniously and peacefully, have different laws, they all meet in one truth: do unto others as you would they should do unto you."

1923 Charles Vickrey creates Golden Rule Sunday, celebrated in the U.S. on the first Sunday of December. Families eat a modest dinner and give the money saved to hunger relief. This later becomes International Golden Rule Sunday.

1923 Arthur Nash's Golden Rule in Business explains how applying the golden rule in his clothing business, besides being right, leads to contented employees who work hard and to contented customers who return.

1923 Annette Fiske's "Psychology" applies the golden rule to nursing: "Some people say every nurse should herself have had a serious illness in order that she may get the patient's point of view. There are few people, however, who do not know the meaning of pain and who do not have sufficient imagination, if they care to exert it, to realize what it means to lie in bed helpless. What is needed is that they should stop to consider these facts, that they should give thought to their patients' feelings as well as to their symptoms and the means to relieve them."

1925 The Coca Cola Company distributes gold-colored golden-rule rulers to school children in the U.S. and Canada.

1929 Leonidas Philippidis writes a German dissertation on the golden rule in world religions: Die "Goldene Regel" religionswissenschaftlich Untersucht.

1930 Sigmund Freud's Civilization and Its Discontents gives a psychological approach unfriendly to the golden rule: "What decides the purpose of life is the pleasure principle. It aims at absence of pain and experiencing of pleasure. There is no golden rule which applies to everyone. 'Love your neighbor as yourself' is an excellent example of the unpsychological proceedings of the cultural super-ego. The commandment is impossible to fulfill." (See my ch. 7.)

c. 1930s Henry Ford, suggesting the role of the golden rule in business, says: "If there is any one secret of success, it lies in the ability to get the other person's point of view and see things from that person's angle as well as from your own."

1932 Leonard Nelson's System of Ethics suggests (my paraphrase): Treat others as if a natural law would turn your way of acting on you.

1934 Joyce Hertzler's "On golden rules" discusses the golden rule from a sociological perspective: the golden rule exists in almost all societies and is a simple and effective means of social control that works from within instead of imposing external rules.

1935 Edwin Embree's "Rebirth of religion in Russia" states: "The central teachings of Jesus were brotherly love without regard to race or caste, the golden rule of doing to others what we would have them do to us, peace, humility, communal sharing of goods and services, the abrogation of worldly treasure. These are directly opposed to just those things which the Christian nations have built their power upon: capitalism, armaments, individualism, disregard of a neighbor of a different race, material wealth."

1936 Dale Carnegie's How to Win Friends and Influence People, a self-help book that sold 15 million copies, is based on the golden rule: "Philosophers have been speculating on the rules of human relationships for thousands of years, and there has evolved only one important precept. Zoroaster taught it to his followers in Persia twenty-five hundred years ago. Confucius preached it in China. Lao-tse, the founder of Taoism, taught it to his disciples. Buddha preached it on the bank of the Ganges. The sacred books of Hinduism taught it a thousand years before that. Jesus summed it up in one thought - probably the most important rule in the world: 'Do unto others as you would have others do unto you.' You want a feeling that you are important in your little world. You don't want to listen to cheap, insincere flattery, but you do crave sincere appreciation. All of us want that. So let's obey the golden rule, and give unto others what we would have others give unto us."

1936 George Herbert Mead's "The problem of society" asks: "If you are going to have a society in which everyone is going to recognize the interests of everybody else - for example, in which the golden rule is to be the rule of conduct - how can that goal be reached?"

1939-45 Nazi genocide kills six million Jews, in one of the greatest moral atrocities ever. What has led to the deterioration of golden-rule thinking?

1940 Michael Rooney founds the Golden Rule Insurance Company. If you search the Web for "golden rule," you'll find golden-rule restaurants, travel agencies, contractors, and tattoo parlors. And you'll find many groups with the golden rule in their motto or mission.

1941 Paul Weiss's "The golden rule" argues that the golden rule works only if we know what we want, what we want is what we ought to desire, and what is good for us is also good for others. He thinks these conditions are usually satisfied.

1942 Ralph Perry suggests (my paraphrase): Treat others in a way that an impartial observer would see as best satisfying all claims.

1943 C.S. Lewis's Mere Christianity (p. 82) says: "The golden rule sums up of what everyone had always known to be right. Really great moral teachers never introduce new moralities: it is quacks and cranks who do that."

1944 A young Martin Luther King wins a high-school speech contest about civil rights. He says "We cannot be truly Christian people so long as we flaunt the central teachings of Jesus: brotherly love and the golden rule."

1946 Jean-Paul Sartre's Existentialism and Human Emotions suggests (my paraphrase): Treat others as if everyone were going to follow your example (and so treat you the same way).

1948 Jean Piaget's Moral Judgment of the Child explains how interacting children move to a higher morality. Young children think revenge is fair: if someone hits you, it's right to hit back. Older children, seeing that this leads to endless revenge, value forgiveness over revenge. Mutual respect grows and expresses itself in the golden rule.

1948 The United Nations Declaration of Human Rights, supported by most nations of the world, begins with a golden-rule like idea: "All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood."

1948 Hans Reiner's "Die Goldene Regel" revives a German discussion on the golden rule that had stalled since Kant's objection (1785). Reiner distinguishes various golden-rule interpretations and tries to answer the objections of Kant and Leibniz.

1948 A high-school teacher in Los Angeles conducts an experiment. Seniors agree to follow the golden rule with their families, without telling them, for 10 days. The results are dramatic. Students find that they get along much better with their families and like living this way, even though their families are perplexed. Many vow to live this way forever. (See my §6.3.)

1950 C.D. Broad's "Imperatives, Categorical and Hypothetical" says "A person ought never to treat others in a way he would not be willing to be treated by others."

1950 Albert Tucker creates the prisoner's dilemma, a game-theory story where two prisoners can do better for themselves if they cooperate instead of following their individual interests. Many discuss how this relates to the golden rule.

1955 C.I. Lewis's Ground and Nature of the Right gives the basic rational imperative as "Be consistent in thought and action." This involves the idea that no way of thinking or acting is valid for anyone unless it's be valid for everyone else in the same circumstances. He gives golden-rule like norms: "Act toward others as if the effects of your actions were to be realized with the poignancy of the immediate - hence, in your own person" and "Act as if you were to live out in sequence your life and the lives of those affected by your actions."

1956 Ullin Leavell introduces the Golden Rule Series of books for moral teaching in public grade schools.

1956 Erich Fromm's Art of Loving says we distort the golden rule if we see it as having us respect the rights of others while caring little about their interests. Instead, the golden rule calls us to oneness and brotherly love.

1957 Leon Festinger's theory of cognitive dissonance explains that we're distressed when we find that we're inconsistent, and so we try to rearrange our beliefs, desires, and actions so that they all fit together. This can be applied to golden-rule consistency: we're distressed when our action (toward another) clashes with our desire about how we'd be treated in a similar situation.

1957 Damon Knight's novel Rule Golden describes a reversed golden rule enforced by aliens, whereby we receive the same treatment that we give to others. This makes it in our interest to follow the golden rule.

1957 Chuck Berry's School Days song mentions the golden rule in the curriculum: "Up in the mornin' and out to school, The teacher is teachin' the golden rule, American history and practical math, You study 'em hard and hopin' to pass."

1958 The Golden Rule ship travels into the Pacific to disrupt and protest the American nuclear atmospheric testing program (which was later stopped).

1958 Kurt Baier's Moral Point of View suggests (my paraphrase): Treat others only as you find acceptable whether you're on the "giving" or the "receiving" end.

1959 Dagobert Runes's Pictorial History of Philosophy begins with a sidebar listing golden-rule sayings in nine world religions. Many similar lists would follow.

1960 Alan Gewirth's "Ethics and normative science" says: "There is good evidence that ideals like the golden rule have seemed no less cogent ethically than non-contradiction and experimentalism have seemed in science."

1961 Monk Thomas Merton's New Seeds of Contemplation (p. 71) explains God's will as requiring that we unite with one another in love: "You can call this the basic tenet of the Natural Law, which is that we should treat others as we would like them to treat us, that we should not do to another what we would not want another to do to us."

1961 Norman Rockwell's Golden Rule painting (showing the golden rule and people from many religions, races, and nations) appears on the cover of the popular Saturday Evening Post magazine. The United Nations wasn't interested when Rockwell wanted to paint it for them as a large mural. But the UN in 1985 put up a mosaic version and today you can buy several other versions of it at http://www.un.org/en (which has hundreds of golden-rule references).

1962 Albrecht Dihle's Die goldene Regel studies the golden rule in ancient Greece and sees it as about self-interest (you do for me and I'll do for you) and retaliation.

1963 Marcus Singer writes that the golden rule has had little philosophical discussion, despite its importance and almost universal acceptance. He discusses absurdities that the usual formulas lead to (e.g., "If I love to hear tom-toms in the middle of the night, does the golden rule tell me to inflict this on others?"). He suggests that we apply the golden rule only to general actions (like treating someone with kindness) and not specific ones (like playing tom-toms). (But we still get absurdities like "If you want people to hate you (as you might do), then hate them.")

1963 R.M. Hare's Freedom and Reason argues that the logic of "ought" supports the golden rule: You're inconsistent if you think you ought to do A to X but don't desire that A be done to you in an imagined reversed situation. Rational moral thinking requires understanding the facts, imagining ourselves in a vivid and accurate way in the other person's place, and seeing if we can hold our moral beliefs consistently (which involves the golden rule). (My book builds on Hare.)

1963 Aldous Huxley writes: "In light of what we know about the relationships of living things to one another and to their inorganic environment - and what we know about overpopulation, ruinous farming, senseless forestry, water pollution, and air pollution - it has become clear that the golden rule applies not only to the dealings of human individuals and societies with one another, but also to their dealings with other living creatures and the planet."

1963 President John Kennedy appeals to the golden rule in calling for an end to racism and segregation. He is assassinated later that year. In 1965, the U.S. government passes a Civil Rights Act; Senator Hubert Humphrey, in the act's closing defense, began by quoting the golden rule.

1964 William Hamilton's "The genetic evolution of social behavior" looks at evolution as the survival of the fittest genes; this leads to sociobiology and discussions about kin altruism, reciprocal altruism, and the golden rule's genetic basis.

1964 Erik Erikson's "The golden rule in the light of new insight" suggests (my paraphrase): Treat others in ways that strengthen and develop you and also strengthen and develop them.

1966 Bruce Alton at Stanford writes one of only two philosophy doctoral dissertations ever written on the golden rule. He proposes this golden rule: "If A is rational about rule R, then if there are reasons for A to think R applies to others' conduct toward A, and A is similar to those others in relevant respects, then there are reasons for A to think R applies to A's conduct toward others."

1966 C.I. Lewis's Values and Imperatives says: "Suppose there are three persons involved in the situation: A, B, and C. Then nothing can be, for you, the right thing to do unless it should still be acceptable to you whether you should stand in the place of A, B, or C."

1966 Senator Robert Kennedy, in a speech in South Africa against racism, appeals to the golden rule: "The golden rule is not sentimentality but practical wisdom. Cruelty is contagious. Where men can be deprived because their skin is black, others will be deprived because their skin is white. If men can suffer because they hold one belief, others may suffer for holding other beliefs. Our liberty can grow only when the liberties of all are secure."

1968 On December 6, R.M. Hare gives a golden-rule talk at Wayne State University in Detroit. On this day, I (Gensler) become a golden-rule junkie, with a love-hate relationship to Hare's golden-rule approach.

1970 Thomas Nagel's Possibility of Altruism says (p. 82): "The rational altruism which I defend can be intuitively represented by the familiar argument, 'How would you like it if someone did that to you?' It is an argument to which we are all in some degree susceptible; but how it works, how it can be persuasive, is a matter of controversy."

1971 John Rawls's A Theory of Justice suggests (my paraphrase): Treat others only in ways that you'd support if you were informed and clear-headed but didn't know your place in the situation.

1971 Robert Trivers's "The evolution of reciprocal altruism" argues that organisms that mutually benefit each other will tend to develop an altruistic concern for each other. This is important for the golden rule's genetic basis.

1977 Harry Gensler at Michigan writes one of only two philosophy doctoral dissertations ever written on the golden rule. He proposes this (like Gold 1): "Don't act to treat another in a given way without consenting to yourself being treated that way in the reversed situation."

1978 Alan Gewirth's "The golden rule rationalized" points out absurdities that common golden-rule sayings lead to and suggests instead (my paraphrase): Treat others only as it's rational for you to want others to treat you - and hence in a way that respects the right to freedom and well-being.

1979 Dr. Bernard Nathanson, who had fought to legalize abortion and later directed the world's largest abortion clinic, now appeals to the golden rule against abortion. His Aborting America (p. 227) rejects his former view as falling "so short of the most profound tenet of human morality: 'Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.'"

1979 Milton Bennett attacks the (literal) golden rule as wrongly assuming that people have the same likes and dislikes. He proposes instead the platinum rule: "Treat others as they want to be treated." (See my §14.1.)

1981 Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard publishes The Path to Happiness. Two chapters discuss easier-to-follow golden rules: "Try not to do things to others that you would not like them to do to you" and "Try to treat others as you would want them to treat you."

1981-4 Lawrence Kohlberg's Essays on Moral Development, based on empirical data, claims that people of all cultures develop moral thinking through six stages. The golden rule appears at every stage, but with higher clarity and motivation at higher stages. We treat others as we want to be treated because this helps us escape punishment (stage 1), encourages others to treat us better (2), wins Mommy's and Daddy's approval (3), is socially approved (4), is a socially useful practice (5), or treats others with dignity and respect (6). We can best teach children the golden rule by discussing moral dilemmas with them and appealing to a stage just higher than what they use in their own thinking.

1983 Germain Grisez's Christian Moral Principles (q. 7-G) sees the golden rule as about how to promote good and respect integral human fulfillment in an impartial way that doesn't unduly favor one person over another.

1983 Hans Reiner's "The golden rule and the natural law" sees the golden rule as about autonomy. The golden rule takes the standards I use in evaluating others and applies them to myself. The golden rule, which all cultures recognize, is the basis for natural law. This suggests (my paraphrase): Treat others following the norms you use to evaluate their actions toward you.

1983 Jürgen Habermas's Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action suggests (my paraphrase): Treat others following norms that all affected parties could ideally accept.

1984 Robert Axelrod has game-theory experts propose strategies for playing matches made up of many prisoner-dilemma episodes. Strategies play against each other on a computer. The winner is TIT FOR TAT, which cooperates on the first move and then mimics what the other party did on the previous move (following "Treat others as they treat you").

1986 H.T.D. Rost, a Bahá'í, publishes The Golden Rule: A Universal Ethic, about the golden rule in world religions.

1986 Pope John Paul II, speaking to world-religion leaders, says: "Jesus Christ reminded us of the golden rule: 'Treat others as you would like them to treat you.' Your various religious creeds may have a similar injunction. The observance of this golden rule is an excellent foundation of peace."

1987 Jeff Wattles's "Levels of meaning in the golden rule" proposes six levels, starting with sensual self-interest ("Do to others as you want them to gratify you") and ending with taking God's love for us as the model of how to love others ("Do to others as God wants you to do to them").

1990 Paul Ricoeur's Oneself as Another connects our self-identity with our narratives about ourselves, where we see ourselves as if we were another. The golden-rule heart of morality is the opposite, to see another as ourself, to feel the pain of another is if it were our own, to act from love.

1990 Paul Ricoeur's "The golden rule," in talking about the golden rule in Luke's gospel, argues that the context rules out a self-interested interpretation (we treat others well just so they'll treat us well), that "Love your enemies" is more demanding than the golden rule but less useful as a general guide, and that the proper motivation for these norms is gratitude for God's love.

1992 Armand Volkas, a drama therapist whose parents were Holocaust survivors, conducts workshops that bring together children of Nazis and children of Holocaust victims. The participants role play, taking the other side's place. Volkas says: "If you can stand in somebody's shoes, you cannot dehumanize that person." (Wattles 1996: 117f)

1992 Harry Handlin's "The company built upon the golden rule: Lincoln Electric" says: "If, as managers, we treat our employees the way that we would like to be treated, we are rewarded with a dedicated, talented, and loyal work force that will consistently meet the needs of the marketplace."

1992 Donald Evans's Spirituality and Human Nature (p. 36) warns against a prideful misuse of the golden rule: I follow the golden rule toward others but don't let others help me.

1993 Mark Johnson's Moral Imagination says (p. 199): "Unless we can put ourselves in the place of another, enlarge our perspective through an imaginative encounter with others, and let our values be called into question from various points of view, we cannot be morally sensitive."

1993 The second Parliament of the World's Religions, led by theologian Hans Küng, overwhelmingly supports a "Declaration for a global ethic" that calls the golden rule "the irrevocable, unconditional norm for all areas of life." For the first time, representatives of the world's religions formally agree on a global ethic.

1993 The Catechism of the Catholic Church says three rules always apply in conscience formation: "One may never do evil so that good may result; the golden rule; and charity always respects one's neighbor and his conscience."

1993 Stephen Holoviak's Golden Rule Management: Give Respect, Get Results explains how to use the golden rule in business.

1994 Neil Cooper's "The intellectual virtues" says: "The readiness to cooperate critically in humility and honesty for the advancement of knowledge is an intellectual virtue required by our goals. We should treat others in argument as we would have them treat us. This is the golden rule of the ethic of inquiry."

1994 Nicholas Rescher's American Philosophy Today proposes this golden rule (p. 72): "In interpreting the discussions of a philosopher, do all you reasonably can to render them coherent and systematic. The operative principle is charity: do unto another as you would ideally do for yourself."

1995 Dan Bruce's Thru-Hiker's Handbook for the AT (Appalachian Trail, a 2000-mile Georgia-to-Maine footpath that I completed in 1979) commends the golden rule as "a good standard to live by on the AT (as in the rest of life), and the relatively few problems that develop among hikers could be eliminated if this simple rule were observed by everyone. It requires that you value and respect your fellow hikers in the same way you expect them to value and respect you."

1996 Jeff Wattles's The Golden Rule, the first scholarly book in English on the golden rule since the 17th century, gives an historical, religious, psychological, and philosophical analysis of the golden rule.

1996 Harry Gensler's Formal Ethics studies moral consistency principles, emphasizing the golden rule.

1996 Confucian scholar David Nivison calls the golden rule "the ground of community, without which no morality could develop: it is the attitude that the other person is not just a physical object, that I might use or manipulate, but a person like myself, whom I should treat accordingly."

1996 Tony Alessandra and Michael O'Connor's The Platinum Rule proposes that, instead of treating others as we want to be treated, we treat others as they want to be treated. (See my §14.1.)

1996 Amitai Etzioni's The New Golden Rule dismisses the golden rule in two brief sentences and gives as the "new golden rule" a norm to balance shared values with individual freedoms: "Respect and uphold society's moral order as you would have society respect and uphold your autonomy." (See my §11.1 Q14.)

1997 Nancy Ammerman's "Golden rule Christians" gives a sociological analysis of liberal Christians who emphasize doing good more than orthodoxy.

2000 Paul McKenna, an interfaith golden-rule activist with Scarboro Missions in Toronto, creates a poster that teaches the golden rule's global importance and presence in the world's religions. The poster has sold 100,000 copies across the globe, with copies in different languages and many prominent places.

2000 Richard Kinnier's "A short list of universal moral values" summarizes research into which values are common to nearly all societies. The golden rule is seen as the clearest and most impressive universal value.

2000s DUO ("Do unto others" - connecting the golden rule with volunteer work to help the larger community) and TEAM ("Treat everyone as me" - emphasizing people helping each other within a given school, sports team, company, or military unit) become popular models for implementing the golden rule.

2001 Tom Carson's "Deception and withholding information in sales" uses the golden rule to determine the duties of salespeople. Carson has us look at proposed practices from the standpoint of the salesperson (who must earn a living), the customer (who wants a good product for a reasonable price), and the employer (who needs to sell products). Any action we propose as permissible must be something we'd consent to in the place of any of the three parties.

2001-9 Republican President George W. Bush in at least eighteen speeches uses some variation of this distinctive golden-rule phrasing: "Love your neighbor just like you'd like to be loved yourself."

2001 Terrorists on 11 September crash hijacked planes into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, killing 3,000 people. A key challenge of the 21st century arises: How can diverse religions live together in peace? This same day, Leslie Mezei is to interview Paul McKenna about his interfaith golden-rule poster (see http://www.interfaithunity.ca/essays/goldenruleposter.htm).

2002 Pam Evans, a world-religions teacher in Wales, is distressed at the bullying of her Muslim students. She designs a Peace Mala interfaith golden-rule bracelet (http://www.peacemala.org.uk), as a symbol of golden rule commitment.

2002 Don Eberly, at the end of his Soul of Civil Society, describes how societies suffer from moral decay and confusion about values. He proposes that we turn to the golden rule, which appeals to people, is rooted in diverse cultures and religions, and gives a solid practical guide for moral living.

2002 Richard Toenjes's "Why be moral in business?" says: "The widespread appeal of the golden rule can be seen as an expression of the desire to justify our actions to others in terms they could not reasonably reject."

2003 John Maxwell's There's No Such Thing as "Business" Ethics claims that the same golden rule covers both personal life and business.

2004 Howard (Q.C.) Terry's Golden Rules and Silver Rules of Humanity in seeking a universal wisdom uncovers a great variety of golden-rule like formulas.

2005 A British television station surveys 44,000 people to create a new "ten commandments." The golden rule was by far the most popular commandment: "Treat others as you want to be treated." (Spier 2005)

2005 Izzy Kalman's Bullies to Buddies describes a golden-rule anti-bullying program. He suggests that victims be calm and treat bullies not as enemies (treating them as they treat you) but as friends (treating them as you want to be treated).

2005 Ken Binmore and others explore the golden rule's role in our hunter-and-gatherer phase. Small, genetically similar clans that use the golden rule to promote cooperative hunting and sharing have a better chance to survive.

2005 Singer Helen Reddy's The Woman I Am (p. 112) recalls her daughter asking, "Mummy, when you're not with me, how can I tell if something is right or wrong?" Reddy answered, "Ask yourself, is this what I'd want someone to do to me? Think about how you'd feel if you were the other person."