- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 5439

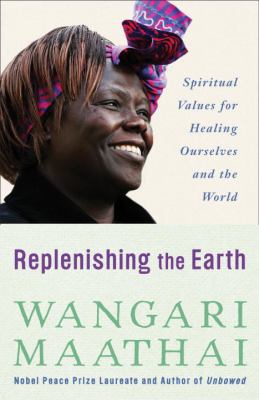

Remembering the Spirit of Nobel Laureate Wangari Maathai

Wangari Maathai (1940-2011) was born in Nyeri, Kenya, in 1940. She was the founder of the Green Belt Movement, which, through networks of rural women, has planted 40 million trees across Kenya since 1977. In 2002, she was elected to Kenya’s Parliament in the first free elections in a generation, and in 2003, she was appointed Deputy Minister for the Environment and Natural Resources, a post she held until 2007, when she left the government. The Nobel Peace Prize laureate of 2004, Matthai was honoured around the world for her work, including an appointment to the Legion d’Honneur by France and the Order of the Rising Sun by Japan. As well as her well known book- Replenishing the Earth: Spiritual Values for Healing Ourselves and the World- she was the author of two previous books: The Green Belt Movement and Unbowed, a memoir, and she regularly gave lectures to organizations around the world. Professor Maathai died on 25 September 2011 at the age of 71 after a battle with ovarian cancer

An impassioned call to heal the wounds of our planet and ourselves through the tenets of our spiritual traditions, from a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize

Replenishing the Earth: Spiritual Values for Healing Ourselves and the World

Photo: betterworldbooks.com

It is so easy, in our modern world, to feel disconnected from the physical earth. Despite dire warnings and escalating concern over the state of our planet, many people feel out of touch with the natural world. Wangari Maathai spent decades working with the Green Belt Movement to help women in rural Kenya plant—and sustain—millions of trees. With their hands in the dirt, these women often find themselves empowered and “at home” in a way they never did before. Maathai wanted to impart that feeling to everyone and believed that the key lies in traditional spiritual values: love for the environment, self-betterment, gratitude and respect, and a commitment to service. While educated in the Christian tradition, Maathai drew inspiration from many faiths, celebrating the Jewish mandate tikkun olam (“repair the world”) and renewing the Japanese term mottainai (“don’t waste”). Through rededication to these values, she believed that, we might finally bring about healing for ourselves and the earth.

"We've become detached from nature," Maathai once remarked. "And as you move away from nature, you become lost."

"I didn't think digging holes and mobilizing communities to protect or restore the trees, forests, watersheds, soil or habitat for wildlife that surrounded them was spiritual work," Maathai remaked.

But over time, her feelings changed. She found what was driving those who joined the Green Belt Movement — and in time, what was driving Maathai herself — wasn't just about fixing material needs. It was about meeting something intangible within people. The poisoning of the earth, the destruction of the forest — Maathai came to believe that human beings could feel these losses. "If we live in an environment that's wounded — where the water is polluted, the air is filled with soot and fumes, the food is contaminated with heavy metals and plastic residues, or the soil is practically dust — it hurts us, chipping away at our health and creating injuries at a physical, psychological and spiritual level," Maathai noted. "In degrading the environment, therefore, we degrade ourselves."

Maathai came to understand, however, that the opposite is true as well. As we work to heal the earth, we heal ourselves as well. There's even an emerging field of treatment behind this — "eco-therapists" have begun prescribing nature walks and time spent outdoors for the depressed. The challenge is that we're growing more and more divorced from nature. Today more than half of the world's population now lives in cities, and even Maathai's largely rural Africa is becoming more and more urbanized, and more and more industrialized. "In Africa, we're busy trying to catch up with the West and live the same kind of life that we see on TV," said Maathai. "But we end up destroying the environment to get the things that we perceive as development."

Maathai was right when she pointed out that we can't forgo the natural connection that we feel for nature, even if we are becoming an urban animal. "A certain tree, forest or mountain itself may not be holy, [but] the life-sustaining services it provides — the oxygen we breathe, the water we drink — are what make existence possible," she wrote. "The environment becomes sacred, because to destroy what is essential to life is to destroy life itself."

Wangari Maathai passed away on 25 September 2011, at the Nairobi hospital, after a prolonged and bravely borne struggle with cancer. She left us too soon. But her legacy is the light that guides our path to build a better world for generations to come.

Her tireless work for a better and sustainable world could be the "simple solution" of faith, strength, wisdom and persistence needed to surmount the escalating challenges of super storms, droughts and other natural disasters of our ever-changing world.

As we mourn the loss of such an important African heroine, let us also celebrate her life and her contributions as we remember five quotes she left behind as seeds for change:

“My heart is in the land and women I came from.”

“African women in general need to know that it’s okay for them to be the way they are – to see the way they are as a strength, and to be liberated from fear and from silence.”

“We can work together for a better world with men and women of goodwill, those who radiate the intrinsic goodness of humankind.” “All of us have a God in us, and that God is the spirit that unites all life, everything that is on this planet. It must be this voice that is telling me to do something, and I am sure it’s the same voice that is speaking to everybody on this planet – at least everybody who seems to be concerned about the fate of the world, the fate of this planet.”

“Today we are faced with a challenge that calls for a shift in our thinking, so that humanity stops threatening its life-support system. We are called to assist the Earth to heal her wounds and in the process heal our own.”

The Passing of a Humming Bird – A Tribute To Prof. Wangari Muta Maathai by the Kenyan poet Mburu Kamau

The bird hummed where eagles feared,

Sang the taboo words,

Tuned to the emancipation of masses,

With an ecstatic difference.

She walked where angels feared,

Talked the language of the voiceless,

When the breeze blew against all odds

And put on a brave march.

As the dawn for our liberation – the Second Birth,

She stood for the truth, with fearless attitude,

And earned a viper’s wrath.

The bird lifted the land high above,

When she held the coveted prize,

For the quest in restoring our dignity,

And we all shouted in her praise.

She fought for you, me and us,

And made us proud,

Our future was restored,

At last, as it ignites our heritage.

Then the wind blew so hard,

That it was too difficult to steer,

Or perch on the nearest tree.

The wing could not move further,

And the sun finally rested on her,

Before, just before the dawn.

The daughter of the African cause,

The tigress that pounces,

The mother of restoring our dashed hope,

The fertility of the land,

The peace beacon of Kenya, Africa, the earth.

Rest in peace,

Prof. Wangari Muta Maathai

Sources consulted for this Blog:

Our History | The Green Belt Movement

Wangari Maathai: Spiritual Environmentalism—Healing Ourselves by Replenishing the Earth

Watch the video:

PRINCE CHARLES HONOURS WANGARI MAATHAI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZT6RmcRPlOE

Read more:

Mother Earth is Crying: A Path to Spiritual Ecology and Sustainability

Visions of a New Earth: Responding to the Ecological Challenge- The Report

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 5953

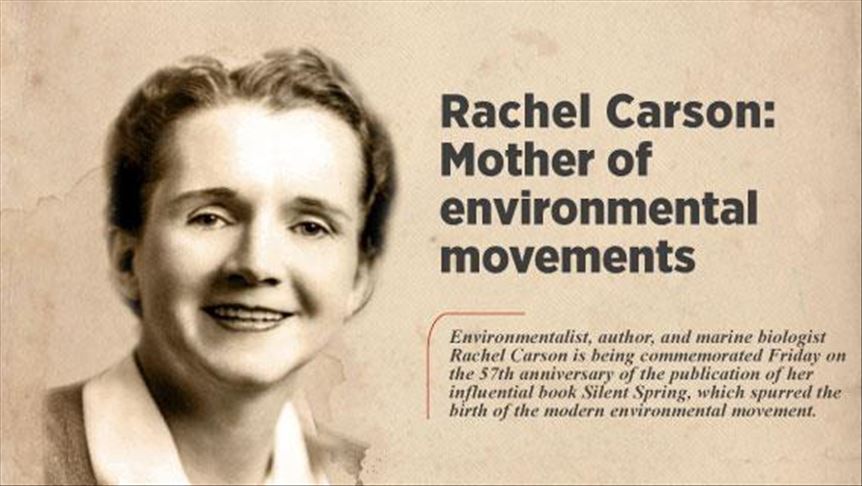

Photo: Facebook

By Steve Szeghi PhD (ECON), Professor of Economics, Wilmington College, Wilmington, Ohio, USA; Co-Author Right Relationship: Building A Whole Earth Economy, and a GCGI Senior Ambassador

‘Let us remember Rachel Carson this April 14th, 2014, fifty years since her death. May her memory enliven our hearts and give us the endurance and passion to fight the battles we need to fight in order to be able to pass on to our children and our grandchildren a beautiful world teeming with the diversity and abundance of life.’

IN MEMORY OF RACHEL CARSON

Photo: Rachel Carson, In Memoriam

Rachel Louise Carson (May 27, 1907 – April 14, 1964)

By Steve Szeghi

'For all of the harm we have caused the natural world since the time of Rachel Carson, at least the springtime is not as yet silent. We are faced though with the prospect of serious climate change, compromised eco-systems, habitat loss, over hunting, over fishing and a multitude of invasive species, all occasioned by human economic activity, greed, and a refusal to modify even in small ways, our lifestyles. But with the coming of the blossoms of spring today; we can still relish the songs of countless aviary species. Spring has not been rendered silent.'

Photo:ytimg.com

'What a fate that would have been! How the world would have been impoverished had it occurred. DDT and many other pesticides have since been strictly regulated. And we have Rachel Carson to thank. With the publication of Silent Spring in 1962, which occurred after the extinction of the Passenger Pigeon, Rachel Carson played a crucial role in getting the world to take seriously numerous environmental threats, among them the threat to birds from the unrestricted use of pesticides. A species so numerous that very few ever contemplated could go extinct, the Passenger Pigeon, had gone extinct and rather quickly in the early 1900’s. The public could easily imagine what spring would be like without the songs of birds. And the public didn’t care much for such a thought. Rachel Carson thus paved the way for the environmental movement, for the Wilderness Act, for the creation of the EPA, along with stricter controls on pesticides.

'We are now at a critical juncture. The environmental movement has stalled, even as climate change intensifies, polar bears face disruption and even extinction, as do the few remaining wild elephants, lions, tigers, gorillas, and grizzlies. In addition many species of birds remain threatened, so much so that unless human beings choose to vastly constrain and modify their actions we may in the foreseeable future face the resurgent threat of a far too real silent spring.

'The very magic and meaning of human life is at stake. The quality of human life depends upon our linkages and connections to the natural world. The very real prospect of massive specie loss fills my heart and soul with an incredible sadness. Human beings may well continue to exist physically for quite some time, for thousands of years even, on a plundered planet without wilderness, and without an abundance of other species and biodiversity. But a world without wild lions, without elephants and polar bears, without gorillas in the wild, and cougars in the mountains, just as readily as a spring without song, will be an impoverished world where human joy and happiness are in short supply.

'What kind of world do we desire to pass on to our children and to our grandchildren? The greatest gift, the greatest inheritance, that we can pass on to posterity is a rich natural world abundantly filled with biodiversity, harmony, and the beauty of this earth. There is treasure in the roar of a lion, in the howl of a wolf, and in the caw of a raven. There is majesty in the flight of an eagle, in a whale breaking the water’s surface taking a breath, and a ram scaling a cliff. There is a marvel in the gaze of a grizzly, in the race of a gazelle, and the gate of a bison.

'Yet there is little that any of us can do to stem the tide of ecological destruction as individuals. There is little we can do alone to pass on to future generations the beauty of the natural world. Voluntary efforts, except as they give encouragement for ultimate collective action, will not be sufficient. We as both national and global communities need to devise bolder incentive structures which safeguard the environment. So very much needs to be done and on so many different levels, global, national, and local. What comes foremost to mind, particularly for the sake of guarding against a potential future silent spring?

'A greater amount of public lands with wilderness designation and enhanced protection is absolutely essential in order to maintain, safeguard, and expand critical habitat for wildlife. Agencies charged with protecting wildlife from poachers and other threats, with safeguarding our air, water, and soil, and with eradicating invasive species need expanded enforcement powers, increased staff and budgets, as well as better state of the art technology. Penalties for environmental and wildlife infractions need to be dramatically increased. Regulatory mandates must sunset particularly troublesome production methods and products. And an assortment of fines, taxes, and penalties must be used to discourage fossil fuel consumption even as subsidies and other incentives are combined to encourage the development of clean energy solution.

'As a child I remember going to the Cincinnati Zoo in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, close to my home, and looking at the memorial to the Passenger Pigeon there. The last known Passenger Pigeon died at the Cincinnati Zoo on September 1, 1914. Her name was Martha. I remember thinking then what would it be like to be the last of one’s species still alive, awaiting death? It struck me as such an utter tragedy as a child. At risk of exposing my childhood sentiments, I could imagine the loneliness Martha might have felt before her death, such a tragedy it seemed to me then. Yet it is a tragedy that we are likely to repeat again and again even as we have already repeated it many times since. Unless we human beings find ways to restructure our economic systems and our lifestyles many species will follow Martha into extinction even as many others flounder far from flourishing, so close to extinctions door.

'Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring was published shortly after my ninth birthday. My parents gave me a copy of Silent Spring for Christmas 1962. I made the connection to the fate of the passenger pigeon. It was quite easy for me as a child to envision what a spring time without song birds would sound like. I could hear in my mind the soulless soundless lack of joy and happiness filling the air. I think I became an environmentalist that Christmas of 1962 and I have my parents and Rachel Carson to thank.

'Let us remember Rachel Carson this April 14th, 2014, fifty years since her death. May her memory enliven our hearts and give us the endurance and passion to fight the battles we need to fight in order to be able to pass on to our children and our grandchildren a beautiful world teeming with the diversity and abundance of life.'

See Also: My Guest Blogger Steve Szeghi: Fifty Years After Silent Spring

KAMRAN MOFID’s GUEST BLOG: Here on The Guest Blog you’ll find commentary, analysis, insight and at times provocation from some of the world’s influential and spiritual thought leaders as they weigh in on critical questions about the state of the world, the emerging societal issues, the dominant economic logic, globalisation, money, markets, sustainability, environment, media, the youth, the purpose of business and economic life, the crucial role of leadership, and the challenges facing economic, business and management education, and more.

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 3345

'Can economics really describe love? Well, it starts with greed…' Image sourced from www.shutterstock.com/

ECONOMICS is “not a ‘gay science,” wrote Thomas Carlyle in 1849. No, it is “a dreary, desolate, and indeed quite abject and distressing one; what we might call, by way of eminence, the dismal science.”

But, happily today, more and more economists are discovering that their discipline is not really a “dismal science”, but a subject of beauty, elegance and relevance, if it was to return to its original roots. More economists are realising that the focus of economics should be on the benefit and the bounty that the economy produces, on how to let this bounty increase, and how to share the benefits justly among the people for the common good, removing the evils that hinder this process. Moreover, they are noticing that economic investigation should be accompanied by research into subjects such as anthropology, philosophy, politics, ethics and spirituality, to give insight into our own mystery, as no economic theory or no economist can say who we are, where have we come from or where we are going to. Humankind must be respected as the centre of creation and not relegated by more short term economic interests.

Two such economists are Professors Paul Frijters and Gigi Foster, whom have recently published a very interesting book on 'humanising economics'. Their book: An Economic Theory of Greed, Love, Groups, and Networks is a compelling reading, where concepts of love, friendship, loyalty, power, coalitions, ideals, joy and compassion are all explored, and are used to temper, leaven and expand the insights of self-interested maximisation.

This is how they explain it:

“Economists understand greed very well; after all, the urge to get rich is our discipline’s main explanation for human actions. Economists further recognise that greed can be good. When our greedy urges are constrained by institutions, so that we compete with each other by means of specialisation in production rather than by killing or cheating one another, our economies produce growth.

But the phenomenon of love has flummoxed us economists. We have followed much of the rest of society in seeing love as something that is a cosmic accident: neither predictable nor manipulable, love has been thought to arise mysteriously. Once finding himself by chance in love, a person suddenly cares about more than just himself. It is allegedly by happy accident that people love their children, their spouses, the constitution of their country, and many other people and constructs.

In our new book, An Economic Theory of Greed, Love, Groups, and Networks, we behold and treat love in an entirely different way. It would be fair to say that we take the stance of aliens looking at humans as just another species, with love merely one behavioural strategy available to that species. Blasphemous as this may sound, our goal is to apply the scientific method to the realm of the heart.

At the most basic level, we contend that love is a submission strategy aimed at producing an implicit exchange. Someone who starts to love begins by desiring something from some outside entity. This entity can be a potential sexual partner, a parent, “society”, a god, or any other person or abstract notion.

From a position of relative weakness, the loving person tries to gain control over this entity by incorporating the entity into his own sense of self. Of many examples, that of the child is perhaps easiest to see in this framework: a weak infant starts to love the parents who provide for his needs, and starts to see himself as part of the family. We contend that the same fundamental process explains why men and women start to love their partners, their countries, their jobs, and their gods.

The consequences of this basic mechanism are immense for any human organisation. Without it, there could be no families, no religions, no science, and no countries, because the loyalty of those who love is part of what keeps families together, soldiers loyal, scientists truth-seekers, and the religious faithful.

Naturally, within any group, not everyone loves to the same degree, and in fact many members of groups do not love at all and instead merely pretend to share the group ideal. But without any real love, created when lovers are weak and needy, human organisations would fall apart and our economies would cease to function.

There is much more to say about love: how it conferred an individual evolutionary advantage long ago; how the neural mechanisms responsible for it relate to our cognitive and non-cognitive development throughout life; how to define weakness and how to describe human desires; how “love” relates to other difficult concepts that economists have long struggled with, such as “power” and “networks”; and, most excitingly, what steps lead from this essentially individual mechanism to the highly organised societal structures we see today. We explore all of these paths in our book. We argue that love is a vital element in almost everything that is important to economists and social science, from why people by and large pay their taxes to why they are able to work happily together in teams.

Why did we decide that love had to have something to do with economics? Because reality forced us into acknowledging the importance of love. If you want to understand yourself and your society but are prepared to make no mental space for love in your explanations, then all we can say is good luck. We hope you have more success than we did. For more than 10 years, we independently worked on understanding society without an explicit role for love, and we basically got stuck. It took us another 10 years to develop our best guess for how love relates to greed and to all of the complexities of humans and their societies.

Finally, why do we see the discipline of economics as the natural home for our theory of love’s genesis and consequences? Because economics offers an extensive discourse on the other crucial ingredient propelling human action – greed – and also because economics is a science whose nature and ideal is to offer simple stories to capture social complexity. By combining love and greed to construct a simple, tractable model of our social world, we hope to have advanced the discovery of what humans and their societies are all about.”

This article was originally published in The Conversation. Read the original article

Buy the book:

Read more:

Calling all academic economists: What are you teaching your students?

Economics and Economists Engulfed By Crises: What Do We Tell the Students?

A comment on a Financial Times editorial (November 12, 2013)

My Guest Blogger Anthony Werner: Ethical Economics