- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 4831

Photo: virtuesforlife.com

On 16 June 2015 I posted a Blog Calling all academic economists: Calling all academic economists: What are you teaching your students? Soon after this I had a very nice email from a young academic economist, at the beginning of his academic journey, full of enthusiasm, commitment and dreams.

He told me that he was very inspired and moved by my Blog. He, too, like me, he noted, sees teaching as a vocation and he had opted to become a university lecturer, believing that it is his mission in life to engage with students with life’s bigger questions, not just teaching them a bit of economics here and there with huge amount of mathematics, statistics and IT.

He then told me that he wishes to prepare a different module for his first year students, something that will make them stop and think about more important questions and aspects of life.

He then asked me if I can shed some light on this, sharing a bit more of what I think is important to teach and perhaps suggest a course that I, myself, would have liked to teach my own first year students, if I was still teaching.

I was so excited and happy to hear from him. What an honourable young man.

I began my research, composing my thoughts and getting things together. I then came across a Blog “Ubuntu Education: Nelson Mandela’s Lasting Legacy” which I had written on 31 December 2013. There I had suggested a possible inspiring economics module.

I then emailed back the young academic. He was very appreciative and excited about the possibility of offering such a module, hoping that the majority of “orthodox” forces at his school would not put a spanner in his works, a fact that I remember very clearly myself, looking back all those years ago.

I hope he will succeed. I wish him and other “heterodox” academic economists well.

Below I have noted my suggested ECON 101 for all those who are thinking along the same lines.

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 5186

To all those imagining a real economics, a wise economist and a just economy:

Why Economists Fail?

In the last couple of weeks I have posted a number of Blogs concerning economics, economy, globalisation, and the common good. I have been humbled by the warmth and positivity of the so many emails I have received, the comments and suggestions.

See the Blogs:

Economics, Globalisation and the Common Good: A Lecture at London School of Economics

Sustainable Development Goals: Where is the Common Good?

Open Letter to Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England

Values, Ethics, and the Common Good in MBA rankings: Where are they?

Calling all academic economists: What are you teaching your students?

Today I received an email from a friend drawing my attention to a very interesting, informative article, “Why Economists Fail?” which is very much related to the Blogs I have been writing.

I very much enjoyed reading it and I now wish to share it with you. I hope my honest and conscientious fellow academic economists and other readers will be sufficiently inspired and thus, we can all come together and demand a better, more relevant, truthful and honest economics teaching.

Why Economists Fail?

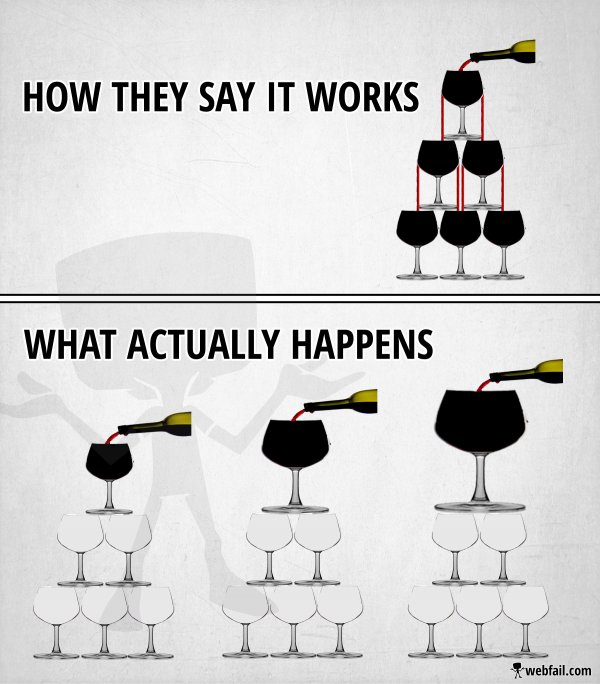

“…Yet there’s a case to be made for discussing economics from a standpoint distinct from that of today’s economists – in fact, from nearly any imaginable standpoint other than that of today’s economists. That case could draw its initial arguments from many points, but the most obvious one just now has to be the near-total failure of contemporary economic thought to provide meaningful guidance to the macroeconomic challenges of our time.

This may seem like an extreme statement, but the facts back it up. Consider the way that economists responded – or, rather, failed to respond – to the late housing boom. This was as close to a perfect textbook example of a speculative bubble as you’ll find in recent history. The very extensive literature on speculative bubbles, going back all the way to Mackay’s Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, made recognizing another example of the species easy enough. All the signs were there: the dizzying price increases, the huge influx of amateur investors, the giddy rhetoric insisting that prices could and would keep on rising forever, the soaring rate of speculation using borrowed money, and the rest of it.

By 2005, accordingly, a good many people outside the economics profession were commenting on parallels between the housing bubble and other speculative binges; by 2006 the blogosphere was abuzz with accurate predictions of the approaching crash; by 2007 the final plunge into mass insolvency and depression was treated in many circles as a foregone conclusion – as indeed it was by then. Yet it’s a matter of public record that among those who issued these warnings, economists – who should have caught onto the bubble faster than anyone – could very nearly be counted on the fingers of one foot. On the contrary, the vast majority of the economists who expressed a public opinion on the subject insisted that the delirious rise in real estate prices was justified and that the exotic financial innovations that drove the bubble would keep banks and mortgage companies safe from harm.

These comforting announcements were wrong. Those who made them had every reason to know at the time that they were wrong. No less an economic luminary than John Kenneth Galbraith pointed out decades ago that in the financial world, the term “innovation” usually refers to the rediscovery of the same limited set of bad ideas that always, without exception, lead to economic disaster. Galbraith’s books The Great Crash 1929 and A Short History of Financial Panics, which chronicle the carnage caused by the same gimmicks in the past, can be found on the library shelves in every school of economics in North America, and anyone who reads either one can find every rhetorical excess and fiscal idiocy of the housing bubble faithfully duplicated in the great speculative binges of the past.

If this were an isolated instance of failure, it might be pardonable, but the same pattern repeats itself as regularly as speculative bubbles themselves. Identical assurances were offered – in some cases, by the identical economists – during the last great speculative binge in American economic life, the tech-stock bubble of 1996-2000. They have been offered by professional economists during every other speculative binge since the profession of economics came into being. Take a wider view, and you’ll find that whenever a professional economist assures the public that some apparently risky course of action is perfectly safe, he is usually wrong.

A colorful recent example was the self-destruction of Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) in the early 1990s. One of the two Nobel laureates in economics on LTCM’s staff announced publicly that the computer models the company used for its hugely leveraged trades were so good that they could not lose money in the lifetime of the universe. Have you ever noticed that villains in bad movies very often get blown to smithereens a few seconds after saying “I am invincible”? Apparently the same principle applies to economists, though the time lag is longer; it was, as I recall, some five years after this announcement that LTCM got blindsided by a Russian foreign-loan default that many other people saw coming, and failed catastrophically. The US government had to arrange a hurried rescue package to keep the implosion from causing a general financial panic.

Economists are not, by and large, stupid people. Those who work in some of the less glamorous subsets of the field have worked out a great many useful tools for businesses and individuals, and the level of mathematical skill to be found among today’s “quants” rivals that of many university physics departments. Yet the profession seems to have become incapable of learning from its most glaring and highly publicized mistakes. This is all the more troubling in that you’ll find many economists among the pundits who insist that industrial economies need not trouble themselves about the impact of limitless economic growth on the biosphere that supports all our lives. If they’re as wrong about that as so many other economists were about the housing bubble, they’ve made a fateful leap from risking billions of dollars to risking billions of lives.

What lies behind this startling blindness to the evidence of history and the reality of the downside? Plenty of factors doubtless play a part, but three seem most important to me.

First of all, for professional economists, being wrong is much more lucrative than being right. During the runup to a speculative binge, and even more so during the binge itself, a great many people are willing to pay handsomely to be told that throwing their money into the speculation du jour is the right thing to do. Very few people are willing to pay to be told that they might as well flush it down the toilet, even – indeed, especially – when this is the case. During and after the crash, by contrast, most people have enough calls on their remaining money that paying economists to say anything at all is low on the priority list.

The same rule applies to professorships at universities, positions at brokerages, and many of the other sources of income open to economists. When markets are rising, those who encourage people to indulge their fantasies of overnight wealth will be far more popular, and thus more employable, than those who warn them of the inevitable outcome of pursuing such fantasies; when markets are plunging, and the reverse might be true, nobody’s hiring. Apply the same logic to the fate of industrial society and the results are much the same; those who promote policies that allow people to get rich and live extravagantly today can count on an enthusiastic response, even if those same policies condemn industrial society to a death spiral in the decades ahead. Posterity, it’s worth remembering, pays nobody’s salaries today.

Second, like many contemporary fields of study, economics suffers from a bad case of premature scientification. The dazzling achievements of science have encouraged scholars in a great many fields to ape science’s methods in the hope of duplicating its successes, or at least cashing in on its prestige. Before Isaac Newton could make sense of the planets in their courses, though, thousands of observational astronomers had to amass the raw data with which he worked. The same thing is true of any successful science: what used to be called “natural history,” the systematic recording of what nature actually does, builds the foundation on which science erects structures of hypothesis and experiment.

A great many fields of study have attempted to skip the preliminaries and fling themselves straight into scientific research. The results are not good, because there’s a boobytrap hidden inside the scientific method. The fact that you can get some fraction of nature to behave in a certain way under arbitrary conditions in the artificial setting of a laboratory does not mean that nature behaves that way left to herself. If all you want to know is what you can force a given fraction of nature to do, this is well and good, but if you want to understand how the world works, the fact that you can often force nature to conform to your theory is not exactly helpful.

Economics is particularly vulnerable to this sort of malign feedback because its raw material – human beings making economic decisions – is so complex that the only way to control all the variables is to impose conditions so arbitrary and rigid that the results have only the most distant relation to the real world. The logical way out of this trap is to concentrate on the equivalent of natural history, which is economic history: the record of what has actually happened in human communities under different economic conditions. This is exactly what those who predicted the housing crash did: they noted that a set of conditions in the past (a bubble) consistently led to a common result (a crash) and used that knowledge to make accurate predictions about the future.

Yet this is not, on the whole, what successful economists do nowadays. Instead, a great many of them spend their careers generating elaborate theories and quantitative models that are rarely tested against the evidence of economic history. The result is that when those theories are tested against the evidence of today’s economic realities, they often fail.

The Nobel laureates whose computer models brought LTCM crashing down in flames, for example, created what amounted to extremely complex hypotheses about economic behavior, and put those hypotheses to a very expensive test, which they failed. If they had taken the time to study economic history first, they might well have noticed that politically unstable countries tolerably often default on their debts, that moneymaking schemes involving huge amounts of other people’s money usually end up imploding messily, and that every previous attempt to profit by modeling the market’s vagaries had come to grief when confronted by the sheer cussedness of human beings making decisions about their money. They did not notice these things, and so they and their investors ended up losing astronomical amounts of money.

The third factor driving the economic profession’s blindness to its own mistakes is more complex, and will demand a post of its own. Few things seem less related than the abstractions of metaphysics and the gritty realities of money, but there’s a crucial connection. Underlying today’s economic thought is a specific set of metaphysical assumptions, and those assumptions form the foundation of sand underneath the proud and unsteady towers of today’s economic theories. In next week’s post I plan on taking a hard look at the metaphysics of money, in the hope of finding a less problematic basis for economic life in the approaching deindustrial age.”

Read the original article:

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 14646

“Don’t just teach your students how to count. Teach them what counts most.”

‘In spite of the utter failure of academic and professional economists to predict, explain or find solutions to the financial and economic crises sweeping the globalised, marketised world they have created, there is still little challenge to the narrow and one-sided way that economics is taught in our universities. In spite of the fact that economics is about complex human relationships, and is therefore bound to be the subject of debate and disagreement, there is no problem with university courses that only teach the neoclassical pro-market approach.’- Gaian Economics

“Economics is only dismal because there are not enough of us making it our own.”

Photo: gaianeconomics.co.uk

ECONOMICS is “not a ‘gay science,” wrote Thomas Carlyle in 1849. No, it is “a dreary, desolate, and indeed quite abject and distressing one; what we might call, by way of eminence, the dismal science.”

But, happily today, some academic economists are discovering that their discipline is not really a “dismal science”, but a subject of beauty, elegance and relevance, if it was to return to its original roots, moral philosophy amid issues and questions of broad significance involving the fullness of human existence.

More economists are now realising that the focus of economics should be on the benefit and the bounty that the economy produces, on how to let this bounty increase, and how to share the benefits justly among the people for the common good, removing the evils that hinder this process. Moreover, they are noticing that economic investigation should be accompanied by research into subjects such as anthropology, psychology, philosophy, politics, ethics and spirituality, to give insight into our own mystery, as no economic theory or no economist can say who we are, where have we come from or where we are going. Humankind must be respected as the centre of creation and not relegated by more short term economic interests.

My question to my fellow academic economists is: Are you one of those "Recovering" economists, and if not, why not?

Students everywhere are calling for pluralism in economics. See below:

So what is economics? What has gone wrong? What is to be done?

Photo: thestash.co

2000- France, the Sorbonne and other universities

“In the spring of 2000 an interesting dichotomy between theory and reality in economics teaching appeared in France when economics students from some of the most prestigious universities, including the Sorbonne, published a petition on the internet urging fellow students to protest against the way economics was being taught. They were against the domination of rationalist theories, the marginalization of critical and reflective thought and the use of increasingly complex mathematical models. Some argued that the drive to make economics more like physics was flawed and that it should be wrenched back in line with its more social aspects”:

In Praise of the Economic Students at the Sorbonne: The Class of 2000

2008- London, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II asking the economists at London School of Economics: “Why did nobody notice?”

Your Majesty,

“I note, with much interest, Your Majesty’s recent visit to the London School of Economics. Given the current financial calamity, Your Majesty asked a very pertinent and important question: “Why did nobody notice?”

I firmly believe that the director of research and his colleagues present there, should have provided Your Majesty with truthful and honest answers. However, given what I have read in the press, I do not believe this was the case. Their failure to do so, clearly goes a long way to prove the detachment of economists and the modern neo-liberal economics from the real world. They have turned our profession and subject into a comedy of errors, a dismal science of irrelevance.

This is very sad indeed Your Majesty. An entire profession now appears to have suffered a collapse. Trust and confidence in my profession has all but been demolished, the “dismal science” at its worst.

Many mistakes have been made. Many economists have compromised themselves and their profession by remaining silent, not criticising the extremism and the neo-liberal fundamentalism present in their profession. Lessons should be learnt, someone should be held accountable. Otherwise the same mistakes will be repeated and nobody will believe what an economist says again. In other words, Your Majesty deserves a proper and honest answer…”

2011- London- “There is no correlation between ethics and economics”- Lord Kalms’ letter to the Times (08/03/2011):

Ethics boys

Sir, Around 1991 I offered the London School of Economics a grant of £1 million to set up a Chair in Business Ethics. John Ashworth, at that time the Director of the LSE, encouraged the idea but had to write to me to say, regretfully, that the faculty had rejected the offer as it saw no correlation between ethics and economics. Quite. Lord Kalms, House of Lords

Economics, Globalisation and the Common Good: A Lecture at LondonSchool of Economics

2011- USA, Harvard University, Students of economics revolting against their professor at Harvard

“There is a growing student protest movement against orthodox economics that could change the field as we know it.” On 2nd November 2011 at HarvardUniversity, students of Prof. N. Gregory Mankiw walked out of his class.

“Mankiw is the former head of the Council of Economic Advisers for President George W. Bush and an advisor to Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney. He is also the author of "Principles of Economics," the predominant textbook used in introductory economics classes worldwide. Not surprisingly, he has an extremely traditional, market-oriented view of the discipline.

The students who walked out of Mankiw's class explained their reasoning in an open letter printed in the Harvard Political Review. It began with this declaration: "Today, we are walking out of your class, Economics 10, in order to express our discontent with the bias inherent in this introductory economics course. We are deeply concerned about the way that this bias affects students, the University, and our greater society.

They went on to explain that instead of presenting a broad introduction to economics, Mankiw's teaching was narrowly focused, did not offer alternative approaches to orthodox economic models and ultimately was complicit in perpetuating systemic global inequality…

These students are frustrated by a field that they believe could provide so much to society but instead is mired in outmoded thinking. Today's economics is dominated by ideas, like the efficient market hypothesis, making such sweeping generalizations that they render human beings practically unrecognizable”…

Goodbye, St Paul's. Hello, St Mary's

2013- Manchester University Economics Students, Post-Crash Economic Society

The Post-Crash Economics Society at ManchesterUniversity

Photo: thegusrdian.com

“What wonderfully good news! Once again, another group of brave students of economics at a university have risen against the “dismal science” and the madness of the neo-clasical economics, its ways and its teachings. I am delighted to hear that the Manchester students have seen the light, like their fellow students at other universities, such as the class of 2000 at the Sorbonne”:

2014- International Student Initiative for Pluralism in Economics (ISIPE) was founded

It is not only the world economy that is in crisis. The teaching of economics is in crisis too, and this crisis has consequences far beyond the university walls. What is taught shapes the minds of the next generation of policymakers, and therefore shapes the societies we live in. We, 42 associations of economics students from 19 different countries, believe it is time to reconsider the way economics is taught. We are dissatisfied with the dramatic narrowing of the curriculum that has taken place over the last couple of decades. This lack of intellectual diversity does not only restrain education and research. It limits our ability to contend with the multidimensional challenges of the 21st century – from financial stability, to food security and climate change. The real world should be brought back into the classroom, as well as debate and a pluralism of theories and methods. This will help renew the discipline and ultimately create a space in which solutions to society’s problems can be generated.

United across borders, we call for a change of course. We do not claim to have the perfect answer, but we have no doubt that economics students will profit from exposure to different perspectives and ideas. Pluralism could not only help to fertilize teaching and research and reinvigorate the discipline. Rather, pluralism carries the promise to bring economics back into the service of society. Three forms of pluralism must be at the core of curricula: theoretical, methodological and interdisciplinary.

International Students call for pluralism in economics

GCGI supports the International Student Initiative for Pluralism in Economics

5 May 2014- An international student call for pluralism in economics

“It is not only the world economy that is in crisis.The teaching of economics is in crisis too, and this crisis has consequences far beyond the university walls. What is taught shapes the minds of the next generation of policymakers, and therefore shapes the societies we live in. We, over 65 associations of economics students from over 30 different countries, believe it is time to reconsider the way economics is taught. We are dissatisfied with the dramatic narrowing of the curriculum that has taken place over the last couple of decades. This lack of intellectual diversity does not only restrain education and research. It limits our ability to contend with the multidimensional challenges of the 21st century - from financial stability, to food security and climate change. The real world should be brought back into the classroom, as well as debate and a pluralism of theories and methods. Such change will help renew the discipline and ultimately create a space in which solutions to society’s problems can be generated.

United across borders, we call for a change of course. We do not claim to have the perfect answer, but we have no doubt that economics students will profit from exposure to different perspectives and ideas. Pluralism will not only help to enrich teaching and research and reinvigorate the discipline. More than this, pluralism carries the promise of bringing economics back into the service of society. Three forms of pluralism must be at the core of curricula: theoretical, methodological and interdisciplinary.

Theoretical pluralism emphasizes the need to broaden the range of schools of thought represented in the curricula. It is not the particulars of any economic tradition we object to. Pluralism is not about choosing sides, but about encouraging intellectually rich debate and learning to critically contrast ideas. Where other disciplines embrace diversity and teach competing theories even when they are mutually incompatible, economics is often presented as a unified body of knowledge. Admittedly, the dominant tradition has internal variations. Yet, it is only one way of doing economics and of looking at the real world. Such uniformity is unheard of in other fields; nobody would take seriously a degree program in psychology that focuses only on Freudianism, or a politics program that focuses only on state socialism. An inclusive and comprehensive economics education should promote balanced exposure to a variety of theoretical perspectives, from the commonly taught neoclassically-based approaches to the largely excluded classical, post-Keynesian, institutional, ecological, feminist, Marxist and Austrian traditions - among others. Most economics students graduate without ever encountering such diverse perspectives in the classroom.

Furthermore, it is essential that core curricula include courses that provide context and foster reflexive thinking about economics and its methods per se, including philosophy of economics and the theory of knowledge. Also, because theories cannot be fully understood independently of the historical context in which they were formulated, students should be systematically exposed to the history of economic thought and to the classical literature on economics as well as to economic history. Currently, such courses are either non-existent or marginalized to the fringes of economics curricula.”…

Continue to read the rest of the statement:

Open Letter — International Student Initiative for Pluralism in Economics

I firmly believe that the academic economists should show true leadership, wisdom and humility by supporting their students’ call for pluralism in economics.

“It is clear that some serious reflection is in order. Not to stand back and question what has happened and why, would be to compound failure with failure: failure of vision with failure of responsibility. If nothing else these current crises of finance, social injustice and environmental devastation present us with a unique opportunity to address the shortcomings of our profession with total honesty and humility while returning the “dismal science” to its true position: a subject of beauty, wisdom and virtue.”…

Economics and Economists Engulfed By Crises: What Do We Tell the Students?

Now, the pertinent question is: Are the students being listened to? The short answer is: NO. Dogmatism and conservatism at departments of economics have won again. Academic economists are not prepared to show leadership, humility and wisdom.

Photo: econintersect.com

As Aditya Chakrabortty writing in the Guardian has noted: “To see how fiercely the academics fight back, take a look at the University of Manchester.”

“Since last autumn, members of the university's Post-Crash Economics Society have been campaigning for reform of their narrow syllabus. They've put on their own lectures from non-mainstream, heterodox economists, even organising evening classes on bubbles, panics and crashes. You might think academics would be delighted to see such undergraduate engagement, or that economists would be swift to respond to the market.

Not a bit of it. Manchester's economics faculty recently announced that it wouldn't renew the contract of the temporary lecturer of the bubbles course, and that students who wanted to learn about the crash would have to go to the business school. The most significant economics event of our lifetime isn't being taught in any depth at one of the largest economics faculties in the country. So what exactly is a Russell Group university teaching our future economists? Last month the Post-Crash members published a report on the deficiencies of the teaching they receive. It is thorough and thoughtful, and reports: "Tutorials consist of copying problem sets off the board rather than discussing economic ideas, and 18 out of 48 modules have 50% or more marks given by multiple choice." Students point out that they are trained to digest economic theory and regurgitate it in exams, but never to question the assumptions that underpin it. This isn't an education: it's a nine-grand lobotomy.

The Manchester example is part of a much broader trend in which non-mainstream economists have been evicted from economics faculties and now hole up in geography departments or business schools. "Intellectual talibanisation" is how one renowned economist describes it in private. This isn't just bad for academia: the logical extension of the argument that you can only study economics in one way is that you can only run the economy in one way.

Mainstream economics still has debates, but they tend to be technical in nature. The Nobel prize winner Paul Krugman has pointed to the recent work of Thomas Piketty as proof that mainstream economics is plenty wide-ranging enough. Yet when Piketty visited the Guardian last week, he complained that economists generate "sophisticated models with very little or no empirical basis … there's a lot of ideology and self-interest".

Like so many other parts of the post-crash order, mainstream economists are liberal in theory but can be authoritarian in practice. The reason for that is brilliantly summed up by that non-economist Upton Sinclair: "It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it."

I must say what a great pity. Can’t they see the magnitude of their failure? Read more below:

Photo: miamiautonomyandsolidarity

Open Letter to Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England

Corruption, Corruption,... Corruption, Everywhere

Values, Ethics, and the Common Good in MBA rankings: Where are they?

Our grandparents were wiser about markets than today’s economists and regulators

Economists Stop teaching 'The World's Dumbest Idea'!

Gaian Economics: Economics in University: Teaching or Propaganda?

What is Economics? A pictorial look:

what is economics - Google Search

If you are not a "Recovered" or "Recovering" academic economist yet, but have been inspired by this Blog to begin your own journey of “Recovery”, I wish to offer you the following as you prepare for your journey:

In February 2012 an international conference: "Economics education after the crisis: Are the graduate economists fit for purpose?" was organised by the UK Government Economic Service, the Bank of England and Royal Economic Society.

In her conference report, Diane Coyle (Chair) - Enlightenment Economics and ESRC Research Committee Member notes the following:

"One of the consequences of the financial and economic crisis since 2008 has been a re-evaluation of economics itself by at least some of its practitioners. This includes looking again at the teaching of economics in universities, the subject of a recent conference supported by the Government Economic Service, the Bank of England and the Royal Economic Society. As a speaker in the opening session of the conference noted ‘The crisis was a large intellectual failure. We all got it largely wrong and have been using the wrong intellectual apparatus.’

The question of whether the teaching of economics in universities needs reform is linked to the underlying question about the intellectual status of economics itself, post-crisis. A number of speakers noted that there had been huge progress in recent decades in some areas of economics, such as auction theory, or development economics, for instance. However, there was a degree of consensus among participants that economists need to acknowledge the limitations of what has been the standard paradigm in the subject for 50 years. Ideally, we now need to combine a greater modesty about the state of knowledge, an insistence on dogged empirical work to the highest scientific standards, and a new eclecticism about what explanation is needed to understand economic phenomena."…

Read the full report:

Teaching Economics After the Crisis

BBC Radio 4 - Teaching Economics After the Crash

One outcome of the Conference was the formation of a steering group, including both academics and employers of graduate economists, to discuss recommendations for reforms to the teaching of economics students in the UK, In this article, Diane summarises the issues discussed and sets out the group's recommendations. I very much recommend this as a very good starting point to all those wishing to begin their "Recovery" journey:

And then in 2012 a selection of papers presented at the conference was published in a very highly recommended book: “What’s the Use of Economics? Teaching the Dismal Science after the Crisis”, Edited by Diane Coyle, London Publishing Partnership, September 2012

“With the financial crisis continuing after five years, people are questioning why economics failed either to send an adequate early warning ahead of the crisis or to resolve it quickly. The gap between important real-world problems and the workhorse mathematical model-based economics being taught to students has become a chasm. Students continue to be taught as if not much has changed since the crisis, as there is no consensus about how to change the curriculum. Meanwhile, employer discontent with the knowledge and skills of their graduate economist recruits has been growing. This book examines what economists need to bring to their jobs, and the way in which education in universities could be improved to fit graduates better for the real world. It is based on an international conference in February 2012, sponsored by the UK Government Economic Service and the Bank of England, which brought employers and academics together. Three themes emerged: the narrow range of skills and knowledge demonstrated by graduates; the need for reform of the content of the courses they are taught; and the barriers to curriculum reform. While some issues remain unresolved, there was strong agreement on such key issues as the strengthening of economic history, the teaching of inductive as well as deductive reasoning, critical evaluation and communication skills, and a better alignment of lecturers' incentives with the needs of their students.”

Read more: What’s the Use of Economics? Teaching the Dismal Science after the Crisis

Why Economics, Economists and Economy Fail?

To all those imagining a real economics, a wise economist and a just economy: Why Economists Fail?

Why Economics, Economists and Economy Fail?

Values to Build a Better World

‘We have to build a better man before we can build a better society.’-Paul Tillich

‘Try not to become a man of success, but a man of value.’ - Albert Einstein

Values: To guard the hope, faith, love, courage, integrity, honesty, peace, justice, ecology, responsible leadership and humanity for the common good that can lead us forward, because they are the foundation for our greatest thoughts, actions, and the hope for our individual/collective sustainability and can never be cast asunder.

Values to Build a Better World

‘Saving economics from the economists’

ECON 101

A suggested first year module for all students majoring in economics

Ubuntu Economics: Economics for Meaning, Social Justice and the Common Good- Where we connect our intellect with our humanity

Prof. Kamran Mofid

Ronald Coase, professor of economics at the University of Chicago Law School and winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics, shortly before his death on September 2, 2013, published an article in the Harvard Business Review, ‘Saving economics from the economists’ (Coase & Wang, 2012). He argued that ‘the degree to which economics is isolated from the ordinary business of life is extraordinary and unfortunate’. ‘In the 20th century, economics identified itself as a theoretical approach of economization and gave up the real-world economy as its subject matter. It thus is not a tool the public turns to for enlightenment about how the economy operates…. It is time to reengage with the economy. Market economies springing up in China, India, Africa, and elsewhere herald unprecedented opportunities for economists to study how the market economy gains its resilience in societies with cultural, institutional, and organizational diversity. But knowledge will come only if economics can be reoriented to the study of man as he is and the economic system as it actually exists’.

There are many heterodox economists who reject the dominant model of rational choice in ‘free’ markets, and want to reconnect the study of the economy to the real world; to make its findings more accessible to the public; and to place economic analysis within a framework that embraces humanity as a whole, the world we live in.

This course, “Ubuntu Economics: Economics for Meaning, Social Justice and the Common Good” with its ‘human economy’ approach shares all these priorities. We believe that economic investigation should be accompanied by research into subjects such as anthropology, psychology, philosophy, politics, ethics and spirituality, to give insight into our own mystery, as no economic theory or no economist can say who we are, where have we come from or where we are going. Humankind must be respected as the centre of creation and not relegated by more short term economic interests.

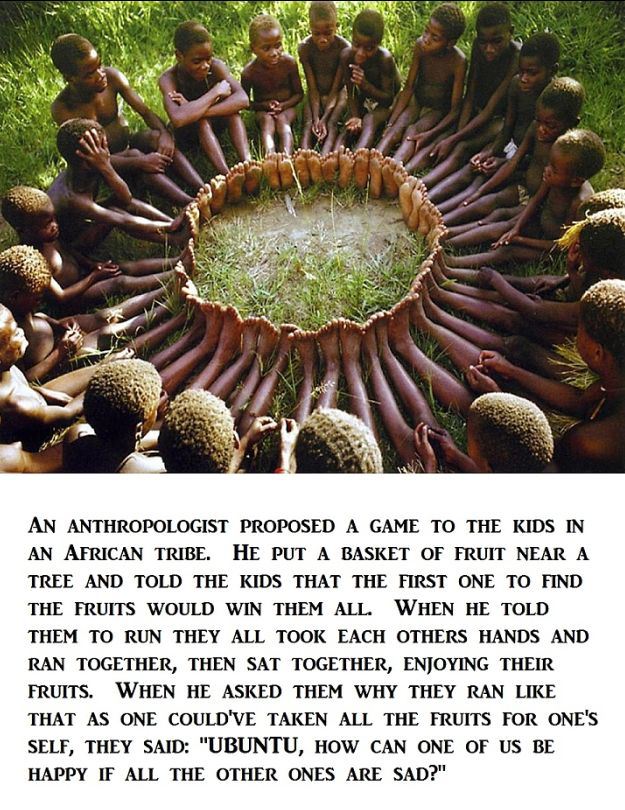

Reverting to Ubuntu Economics:

As it has been said, “Africa, the birthplace of the first human, may just hold the key to the survival of humanity. How fitting and appropriate that the country where homo erectus was first identified is also the birthplace of the philosophy that points the way toward a sustainable future for us, its offspring.

No, I'm not talking about a new technology that will solve our dependence on non-renewable energy resources or that will stop climate change. Not directly at least. But I am talking about a way of seeing the world and all its inhabitants that, if adopted by a critical mass of human beings, would have a major impact in our ability to work together and ultimately shift the context of what it means to be a human being living on Planet Earth in the 21st century.

The philosophy is simple enough. It does however require a massive shift in how we think about ourselves, how we see each other, and how we view every other living thing on the planet.

I'm talking about the philosophy called "Ubuntu," which translated means "I am what I am, because of who we all are." The word "ubuntu" has its origins in the Bantu languages of southern Africa.”

In all, when we speak about the Ubuntu Spirit, we’re referring to the spirit of oneness, unity, love, peace and compassion, which expresses itself in a desire to help others and includes everyone. As Nelson Mandela explains, “The spirit of ubuntu – that profound African sense that we are human only through the humanity of other human beings – is not a parochial phenomenon, but has added globally to our common search for a better world.”

Moreover, as it has been observed by many, people are not individuals, living in a state of independence. They are part of a community, living in relationships and interdependence. This is in stark contrast to neo-classicals who emphasise the individual and its egoism as the engine of economics and business.

Course outline:

What is Ubuntu?

Ubuntu: The philosophical, theological, and spiritual underpinnings

Ubuntu: The economic values. How do they differ from the neo-classical values?

Ubuntu in Africa

What can the West learn from African spirituality and ubuntu?

Ubuntu’s role in community cohesion and transformation

Ubuntu’s role in health-care provision and allocation of resources

Ubuntu business: What is it?

Examples of ubuntu transforming the CEOs and their businesses

The spirit of ubuntu and philanthropy

Ubuntu and the Bottom Line

What does Ubuntu tell us about?

Empathy, cooperation, and sharing over retribution and competition, and inclusivity over exclusivity

Read more:

Ubuntu Education: Nelson Mandela’s Lasting Legacy

Photo: globalelite.tv