- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 4238

We are more than taxpayers!

Taxes, if informed by the common good, can be a positive way to fulfill our calling to do public justice. Photo:bing.com

These days, led by neoliberalism, we are more likely to hear ourselves referred to as “taxpayers” than “citizens.” What if we viewed ourselves as citizens first? We might stop asking “what’s in it for me?” and begin to ask “what’s in it for everyone?”

As it has been noted by many with an eye on justice, fairness and the common good, ‘Taxes raise the revenues used to pay for democratic institutions and to provide government programmes and services. Taxes can also be used to promote other economic and social policy goals through the use of tax expenditures. Over the past decade, significant changes have been made to our tax system, including deep cuts to tax rates. The impact of these changes is cause for concern: there has been a significant loss or erosion of public services that benefit us all, a loss of progressivity in the tax system, and growing income inequality between the rich and the poor with significant costs and consequences for all.

At the same time, there has been an erosion of democratic control and accountability for taxation and public spending. The context for debate has also been very hostile to an open and honest conversation about taxes and the services they pay for. A more positive perspective on taxes views them as an important part of citizenship and democratic representation and a contribution to the common good.

A related perspective views taxes as dues paid in recognition of the common wealth each citizen benefits from, passed on by earlier generations. Taxes can also represent a form of income redistribution over the course of an individual lifetime, as well as an efficient and effective way for individuals to procure services by doing so collectively. Taxes are also an important form of income redistribution in society.

Taxes are one way in which we as citizens fulfil our obligation to promote justice and to respect the right of all people to live in dignity. For governments, tax policy can be used to foster justice, in addition to tax revenues paying for infrastructure and public services that benefit all and promote an equitable society. Public justice also supports a progressive distribution of taxes, and transparent and accountable decisions from governments on taxation and spending.’

Following on what was noted above, today I read a very interesting article on how we may be able to explain and understand ‘tax as a force for common good’, which I very much enjoyed reading and thus, would like to share it with you.

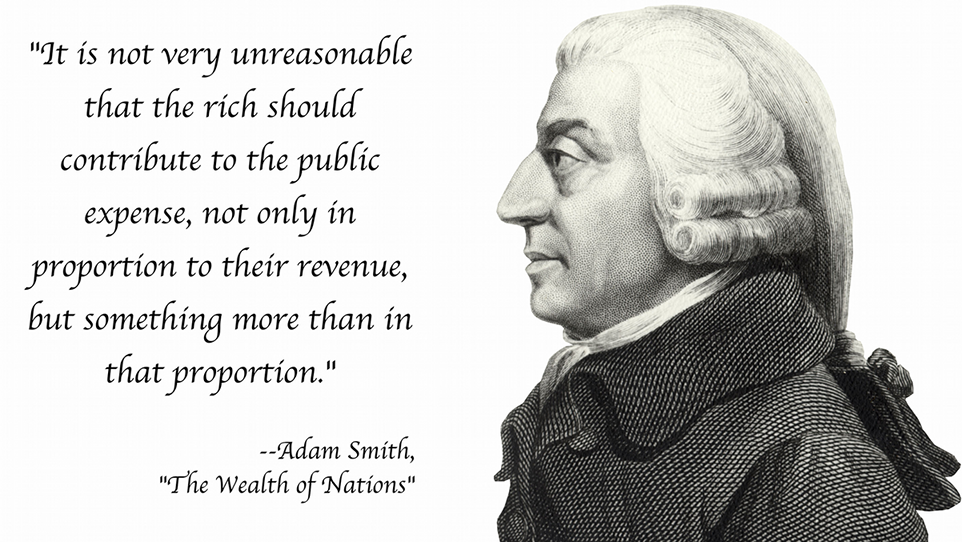

However, in order to appreciate the wisdom of this article, it is necessary to understand and to get-to-know the real Adam Smith. This is important. As the article has highlighted, it is the organisations, such as the Adam Smith Institute, that have poisoned the debate on “Taxation” by using the different Adam Smith, to the one I discovered many years after being a student of economics, or indeed, when I became an economic lecturer. Let me explain a bit more by quoting a passage or two from an article I had written a while back:

Photo: imgur.com

‘These days I am inspired by the “Real” and “True” Adam Smith, known the world over as the Father of New Economics. We should recall the wisdom of Adam Smith, who was a great moral philosopher first and foremost. In 1759, sixteen years before his famous Wealth of Nations, he published The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which explored the self-interested nature of man and his ability nevertheless to make moral decisions based on factors other than selfishness. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith laid the early groundwork for economic analysis, but he embedded it in a broader discussion of social justice and the role of government. Today we mainly know only of his analogy of the ‘invisible hand’ and refer to him as defending free markets; whilst ignoring his insight that the pursuit of wealth should not take precedence over social and moral obligations.

We are taught that the free market as a ‘way of life’ appealed to Adam Smith but not that he thought the morality of the market could not be a substitute for the morality for society at large. He neither envisioned nor prescribed a capitalist society, but rather a ‘capitalist economy within society, a society held together by communities of non-capitalist and non-market morality’. As it has been noted, morality for Smith included neighbourly love, an obligation to practice justice, a norm of financial support for the government ‘in proportion to [one’s] revenue’, and a tendency in human nature to derive pleasure from the good fortune and happiness of other people.

He observed that lasting happiness is found in tranquillity as opposed to consumption. In their quest for more consumption, people have forgotten about the three virtues Smith observed that best provide for a tranquil lifestyle and overall social well-being: justice, beneficence (the doing of good;active goodness or kindness;charity)and prudence (provident care in the management of resources;economy; and frugality).

I am only very sorry that, no one taught me these when I was a student of economics, and then, I did not tell the truth about Adam Smith to my students when I became an economics lecturer; something that I very much regret and something that am trying hard to rectify, now that I am a “Recovering and Repenting” economist for the common good. At the end of the day, it is our honesty, humility and our struggle to seek the truth that will set us free and allow us to hold our head high, nothing less, nothing more.”

Now that I have introduced you to the real Adam Smith, let me share the article I was talking about with you:

‘Let’s talk about tax as a force for common good – or we lose the debate’

‘Tax Freedom Day is another sad example of how our contribution to society is regarded as theft. This cannot go unchecked’

‘For the first 212 days of the year, every penny you’ve earned you’ve kept for yourself. In the meantime, you’ve been enjoying and helping others enjoy the health service for free.’- Photo: bing.com

31 July should have been a day of great civic celebration. For the first 212 days of the year, every penny you’ve earned you’ve kept for yourself. In the meantime, you’ve been enjoying and helping others enjoy the health service, public education, kerbside waste collection, policing, defence, pensions, roads and welfare payments, all for free. Only since Sunday have you started to contribute your share to all these and many more benefits of a modern, developed state.

No one is celebrating such a social solidarity day yet. However, for several years the Adam Smith Institute and the Taxpayers Alliance have been advocating something they call tax freedom day, which fell this year on 3 June. They tout this as “the first day of the year that you start earning money for yourself”, since on average all we earn for 154 days of the year we pay in taxes.

Social solidarity day and tax freedom day are of course two ways of looking at exactly the same objective phenomenon: that on average, 154 calender days earnings are taxed. The meaning of this fact, however, is changed by how we frame it. For economic libertarians, taxation is a deprivation of what is ours by natural right. For those who favour a welfare state, taxation is (or at least should be) a fair payment towards a well-functioning, just society that protects the weak as well as the strong.

Tax freedom day has been an effective rhetorical tool for advancing the tax-as-theft worldview. It is now as politically difficult to speak positively of tax as it is easy to praise the things we spend these taxes on, as though we can be in favour of the NHS while being against what funds it.

The demonisation of tax is part of a wider ideological battle to get us to think more like Americans and less like our fellow Europeans. Government is portrayed not as the servant of the people but as our tyrannical master. The state doesn’t act on our behalf, it interferes in our affairs. We are not governed in but ruled by London and Brussels.

The spread of these ways of thinking have contributed to the decline in trust in politics and disdain for mainstream politics. Countering it is a vital task for all who value anything like European social democracy. This requires reframing the debate around taxation in three key ways.

First, there is the issue of waste and inefficiency in government spending. This is real but often exaggerated. For example, international reports have repeatedly shown that the NHS is one of the most, if not the most, efficient health systems in the world. Where there is waste, however, we increasingly see only an opportunity to cut.

For example, last year the Labour peer Lord Carter led a review which suggested up to £5bn per year could be saved in the NHS through procurement improvements and minimising the use of agency staff. Almost everyone took this as meaning we could spend £5bn less on the NHS when it could equally mean having an extra £5bn to spend expanding services. Time and again the war on waste is waged in the name of tax cuts when it could be fought in the cause of better services.

Second is the issue of fairness. Take the complaint that multinationals operating in the UK pay hardly any tax here. Too often it is assumed that this means that others are paying too little and so we are paying too much. The key problem, however, is simply that taxes that could help run the country are going uncollected. The debate has become one about paying a fair share when it is more importantly one about increasing the size of the pot we pay into.

Third, we need to counter the subtle ways in which we are complicit in the taxophobics’ game. Think about how every newspaper and news outlet reports the budget. The bottom line is always presented in terms of whether tax changes leave specific types of people better or worse off, usually by mere pennies per week. The most important test of a budget should not be how taxes hit individuals’ pockets, but whether overall government is sustainably improving the state of the nation. Taxing less than we need to is as bad as taxing more than is necessary.

These changes in how we think and talk might strike you as modest and uncontroversial. Proof that they are anything but is that a campaign to start celebrating social solidarity day would today be laughed off as some kind of politically correct joke. Unless and until we make it normal to see taxation primarily as a valuable contribution to our own and the common good, the narrative that government is the enemy and tax is theft will continue to prevail.

This article was first published in the Guardian on Monday 1 August 2016.

See the original article:

Let’s talk about tax as a force for common good – or we lose the debate

For further reading see:

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 1583

Money, Money, Money. What is money for? Photo: britannica.com

‘Our attitude towards wealth played a crucial role in Brexit. We need a rethink’

‘Money was a key factor in the outcome of the EU referendum. We will now have to learn to collaborate and to share’

‘But we can and will succeed. Humans are endlessly resourceful, optimistic and adaptable. We must broaden our definition of wealth to include knowledge, natural resources, and human capacity, and at the same time learn to share each of those more fairly. If we do this, then there is no limit to what humans can achieve together.’ Photo: rawstory.com

Does money matter? Does wealth make us rich any more? These might seem like odd questions for a physicist to try to answer, but Britain’s referendum decision is a reminder that everything is connected and that if we wish to understand the fundamental nature of the universe, we’d be very foolish to ignore the role that wealth does and doesn’t play in our society.

I argued during the referendum campaign that it would be a mistake for Britain to leave the European Union. I’m sad about the result, but if I’ve learned one lesson in my life it is to make the best of the hand you are dealt. Now we must learn to live outside the EU, but in order to manage that successfully we need to understand why British people made the choice that they did. I believe that wealth, the way we understand it and the way we share it, played a crucial role in their decision. As the prime minister, Theresa May, said in her first week in office: “We need to reform the economy to allow more people to share in the country’s prosperity.”

We all know that money is important. One of the reasons I believed it would be wrong to leave the EU was related to grants. British science needs all the money it can get, and one important source of such funding has for many years been the European commission. Without these grants, much important work would not and could not have happened. There is already some evidence of British scientists being frozen out of European projects, and we need the government to tackle this issue as soon possible.

Money is also important because it is liberating for individuals. I have spoken in the past about my concern that government spending cuts in the UK will diminish support for disabled students, support that helped me during my career. In my case, of course, money has helped not only make my career possible but has also literally kept me alive.

On one occasion while in Switzerland early on in my career, I developed pneumonia, and my college at Cambridge, Gonville and Caius, arranged to have me flown back to the UK for treatment. Without their money I might not have survived to do all the thinking that I’ve managed since then. Cash can set individuals free, just as poverty can certainly trap them and limit their potential, to their own detriment and that of the human race.

So I would be the last person to decry the significance of money. However, although wealth has played an important practical role in my life, I have of course had a different relationship with it to most people. Paying for my care as a severely disabled man, and my work, is crucial; the acquisition of possessions is not. I don’t know what I would do with a racehorse, or indeed a Ferrari, even if I could afford one. So I have come to see money as a facilitator, as a means to an end – whether it is for ideas, or health, or security – but never as an end in itself.

Interestingly this attitude, for a long time seen as the predictable eccentricity of a Cambridge academic, is now more widely shared. People are starting to question the value of pure wealth. Is knowledge or experience more important than money? Can possessions stand in the way of fulfilment? Can we truly own anything, or are we just transient custodians?

These questions are leading to a shift in behaviour which, in turn, is inspiring some groundbreaking new enterprises and ideas. These are termed “cathedral projects”, the modern equivalent of the grand church buildings, constructed as part of humanity’s attempt to bridge heaven and Earth. These ideas are started by one generation with the hope a future generation will take up these challenges.

I hope and believe that people will embrace more of this cathedral thinking for the future, as they have done in the past, because we are in perilous times. Our planet and the human race face multiple challenges. These challenges are global and serious – climate change, food production, overpopulation, the decimation of other species, epidemic disease, acidification of the oceans. Such pressing issues will require us to collaborate, all of us, with a shared vision and cooperative endeavour to ensure that humanity can survive. We will need to adapt, rethink, refocus and change some of our fundamental assumptions about what we mean by wealth, by possessions, by mine and yours. Just like children, we will have to learn to share.

If we fail then the forces that contributed to Brexit, the envy and isolationism not just in the UK but around the world that spring from not sharing, of cultures driven by a narrow definition of wealth and a failure to divide it more fairly, both within nations and across national borders, will strengthen. If that were to happen, I would not be optimistic about the long-term outlook for our species.

But we can and will succeed. Humans are endlessly resourceful, optimistic and adaptable. We must broaden our definition of wealth to include knowledge, natural resources, and human capacity, and at the same time learn to share each of those more fairly. If we do this, then there is no limit to what humans can achieve together.

This article was first published in The Guardian on Friday 29 July 2016

Read more:

Dear Prime Minister-Britain needs a New Economic Model

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 5147

"The Government I lead will be driven not by the interests of the privileged few but by you. We won't entrench advantages of the fortunate few. We will do everything to help you go as far as your talents can take you.We must fight the burning injustices. We must make Britain a country that works for everyone.”-Photo: upi.com

Dear Prime Minister,

May I firstly offer my congratulations to you on your 'selection' by your memebership as Prime Minister; I wish you every success in this role.

I was most pleased to note your commendable goals to reform our crises-prone capitalism. This is music to my ears, so to say.

This was so, until this morning, when I read in today’s papers that your administration has steadfastly refused to explain how you may “reform capitalism”, so desperately needed, given the examples set by our “Noble” knighted business leaders, such as the likes of Sir Philip Green who have broken our country to pieces, sinking it to lowest levels of decency and humanity.

Photo: pbs.twing.com

I know you are very busy sorting out other peoples’ mess, the Brexit. Therefore, I will try to be as brief as I can, in offering my humble opinion on how you may reform our feral and values-less capitalism:

1- Please do not listen to your new policy chief, George Freeman, or for that matter, your new international trade secretary, Liam Fox. From what I have read about them, they are a Thatcherite, free-marketeer, neo-liberal-obsessed individuals.

Please no more fooling of the masses. The world is facing a crisis of humanity. One thing is clear: These crises have the same global currency- the inhumane, values and moral-free neoliberalism.

What your policy chief, or your international trade secretary are telling you is a so-yesteryears model. Please be aware of the dark forces in your midst!

Thatcherism is now very much discredited; even the IMF- the once main cheerleader for neo-liberalism- has disowned and rubbished it. I am sure you must be aware of their recent report: Neoliberalism: Oversold?

Given the importance of this timely thinking, I wish to offer you a couple of more readings, so as we leave no stones unturned:

People’s Tragedy: Neoliberal Legacy of Thatcher and Reagan

The Destruction of our World and the lies of Milton Friedman

Now the Big Question: How may the feral, greedy, dishonest, selfish and untrustworthy capitalism be reformed?

The answer is: Very easy indeed, if heart and mind work together in harmony for the common good.

2- Please reform our education system and model: It is the current educational values that have given respectability to feral capitalism.

So away with the current model and usher in the new education model:

"Education to Build a Better Future for All"

Some say that my teaching is nonsense.

Others call it lofty but impractical.

But to those who have looked inside themselves,

this nonsense makes perfect sense.

And to those who put it into practice,

this loftiness has roots that go deep.

I have just three things to teach:

simplicity, patience, compassion.

These three are your greatest treasures.

Simple in actions and in thoughts,

you return to the source of being.

Patient with both friends and enemies,

you accord with the way things are.

Compassionate toward yourself,

you reconcile all beings in the world.- Lao Tzu

'We live in a world with many complex problems, at all levels, local, regional and global. It is said that education is the key that opens the door to a more harmonious world.

The pertinent question is: What kind of education and learning would help us address these challenges and create a sustainable world and a better life for all?

T.S. Eliot posed the question: "Where is the Life we have lost in living? Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?"

Reflecting on the questions above, we are going to need an education system that respects planetary boundaries, that recognises the dependence of human well-being on social relations and fairness, and that the ultimate goal is human well-being and ecological sustainability, not merely growth of material consumption.

The new education model recognises that the economy is embedded in a society and culture that are themselves embedded in an ecological life-support system, and that the economy can't grow forever on this finite planet.

In short, we need to listen to our hearts, re-learn what we think we know, and encourage our children to think and behave differently, to live more in synch with Nature.

If we do this successfully we can become wiser as a species, more “eco-logical.” We and the planet that gave birth to us can be happier and healthier, healed and transformed.'...

The Journey to Sophia: Education for Wisdom

Our Emotional Inheritance and the need for Emotional Education

3- The rise in corruption must be tackled head-on.

Based on my own extensive experience and observation, I must admit that the ordinary British are not corrupted so far. But many institutions, high-ranking officials, MPs, Lords, business and financial leaders, media tycoons, and more have become corrupted to the core, since the rise of Thatcherism with its inhumane values.

This has resulted in a huge erosion of trust at every level, destroying the fabric of our society.

How can we restore trust? We need to be guided by the values that are not informing our actions today, the values that have brought us disaster, leading to the continuation of crises after crises.

Values-led action to eradicate corruption

The Value of Values: Why Values Matter

4- We need to encourage simplicity and a more simple life.

“Simplicity is not grinding poverty: It is not the polar opposite of wealth. To live simply is to pursue a quiet path of moderation. In a life of balance between opposite extremes lies inner happiness.

People everywhere, in their quest for happiness outside themselves, discover in the end that they’ve been seeking it in an empty cornucopia, and sucking feverishly at the rim of a crystal glass into which was never poured the wine of joy."...

Why a Simple Life Matters: The Path to peace and happiness lies in the simple things in life

5- And finally, if we are true to ourselves, if we truly wish to reform this horrible economic system, then, there is only one option:

All we do has to be for the common good. Our economy must become just, and all our actions should be taken in the interest of the common good. No ifs or buts, if we are truly serious and honest.

How may we achieve that?

What might an Economy for the Common Good look like?

Thank you prime minister. I do hope you may find time to reflect and ponder on the common good, as you formulate your economic policies in more detail.

The time is now for a radical departure from our recent troubled past. Let us seize this opportunity and stand side by side to build a better, kinder, and a more gentle Britain for the good of all. Carpe Diem!

- Doing Good for the Common Good is Good for Us: A Proven Fact Now

- Our Emotional Inheritance and the need for Emotional Education

- Brexit: The Key Lessons- Now is the time for hope to build on the ruins

- EU Referendum: An Open Letter to British people - One man's view of Britain and the British

- In this troubled world let the beauty of nature and simple life be our greatest teachers