- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 2551

This is the Manifesto to Make the World Great Again

The key that will unlock the door to world’s greatness is values-led education

Photo: missionself.com

As Nelson Mandela used to remind us again and again, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world. ”Education is the key to eliminating gender inequality, to reducing poverty, to creating a sustainable planet, to preventing needless deaths and illness, and to fostering peace, harmony, justice, egalitarianism, equality, good race relations, progress and prosperity, for many and not the few.

In short, education is an investment, and for that matter, it is one of the most critical investments we can make. I hope that one day soon this will be realised by all, and thus, when it comes to the annual governmental budget allocations, to my mind, spending on education should not be seen as expenditure, but as an investment in people and in humanity.

T.S. Eliot posed the question: "Where is the Life we have lost in living? Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?"

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 2227

“Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.”- Nelson Mandela

This is a Book on Values-led Education that can Change the World for the Better

Photo:amazon.co.uk

About the Authors

Salim Vally and Enver Motala are two of South Africa’s most outspoken critics of the ‘there is no alternative’ view to the hegemonic neoliberal approach to economic development and the place of education within it. In this text they, and a number of eminent colleagues, provide one of the few elaborations in the country of what is wrong with human capital theory, with supply side approaches framing economic policy and with current education strategies which privilege individual advancement.

About the Book

‘Education, Economy and Society is a compelling and comprehensive antidote to the misconstrued nature of the relationship between education and society. It provides a constructive critique of conventional discourses but also alternative approaches to understand the connections between education and the triple scourge of unemployment, inequality and poverty.

Against a tendency to reduce the skills discourse to narrow economic ends, the contributors passionately argue that education finds its value and purpose in a focus on social justice, transformation and democratic citizenship. The joy of education is to capture human imaginations and unleash their creativity towards a more humane and compassionate society.

Here is a rich resource for educators, policy developers, trade unionists, and trainers to explore possibilities for a new pedagogy in post-school education and training through empirical research on skills, technology and issues of employment on the shop floor, critical analysis of the youth wage subsidy and workers’ education. The book will appeal to a wide audience including students and academics in the fields of industrial sociology; economics; adult education; further education and training; and those in youth development.’- See more and purchase this book HERE

...And now read an excellent review of this timely and excellent book and discover how neoliberalism has destroyed democracy, humanity, justice, education and the common good.

Neoliberal policies destroy human potential and devastate education

Steven J Klees, Via Mail&Guardian

Photo:mg.co.za

‘Finding a solution to the triple challenge of poverty, inequality and unemployment has been unproductively directed towards addressing the lack of individual skills and education instead of focusing on capitalism and other world system structures – whose very logic makes poverty, inequality and lack of employment commonplace..

‘We live in an unfair and unequal world. In South Africa, as well as around the world, much attention has been focused on what has been called the “triple challenge”: job creation, poverty reduction and inequality reduction. The dominant response to all three problems is to argue for increased education and skills.

This excellent new book, Education, Economy and Society, edited by Salim Vally and Enver Motala, offers an in-depth critique of the concepts, frameworks, interventions and logic that underlie this dominant response as well as the one that underlies much of the South African education and training policy. Among its many virtues, the book offers a critique of the three basic discourses that are used to support education and skills solutions to current problems.

The “mismatch discourse” goes back at least to the 1950s. In it, education has been blamed for not supplying the skills that business needs.

It is, unfortunately, true that many children and youth around the world leave school without the basic skills necessary for life and work. But the mismatch discourse is usually less about basic skills and more about vocational skills. The argument, though superficially plausible, is not true for at least two reasons.

On the job

First, vocational skills, which are often context-specific, are generally best taught on the job. Second and fundamentally, unemployment is not a worker-supply problem, but a structural problem of capitalism. There are three or more billion unemployed or underemployed people on this planet, not because they don’t have the right skills but because full employment is neither a feature nor a goal of capitalism.

Underlying the skills discourse is the “human capital discourse”. In the 1950s and earlier, the neoclassical economics framework that underpins capitalist ideology and practice could not explain labour. Although the overall neoclassical framework was embodied in mathematical models of a fictitious story of supply and demand by small producers and consumers, it was not clear how to apply that to labour, work and employment.

Instead, in that era, labour economics was more sociological and based on the real world, trying to understand institutions such as unions and large companies, and phenomena such as strikes, collective bargaining and public policy.

The advent of human capital theory in the 1960s offered a way to deal with labour in terms of supply and demand (mostly supply), as a commodity like any other. This took the sociology out of labour economics. Education was seen as an investment in individual skills that made one more productive and employable.

Although this supply-side focus is sometimes true, it is very partial, at best. That is, abilities such as literacy, numeracy, teamwork, problem-solving, critical thinking and so on can have a payoff in the job market, but only in a context where such skills are valued.

Demand-side questions

The more useful and important question is the demand-side one, usually ignored by human capital theorists, regarding how we can create good jobs that require valuable skills. The human capital discourse also ignores the value of education outside of work.

In fact, contrary to the hype, the human capital discourse, and offshoots of it – such as the knowledge economy – has been one of the most destructive ideas of this century and the one before.

Finding a solution to the triple challenge of poverty, inequality and unemployment has been unproductively directed towards addressing the lack of individual skills and education instead of focusing on capitalism and other world system structures – whose very logic makes poverty, inequality and lack of employment commonplace.

Underlying the human capital discourse, most directly since the 1980s, has been the “neoliberal discourse”. This is tied to neoclassical economics. From the 1930s to the 1970s, in various countries, a liberal neoclassical economics discourse predominated. This discourse recognised some of the inequalities inherent in capitalism and argued the need for government interventions as a corrective.

Government interference

With political shifts exemplified by Ronald Reagan in the United States, Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom and Helmut Kohl in Germany, a neoliberal neoclassical economics discourse took over, which argued that capitalism was both efficient and equitable, that problems were generally minor, and that the source of any problems was too much government interference.

This discourse has gone beyond economics and has political, social and cultural dimensions. In education, the upshot of neoliberal discourse has been to ignore the problems faced by public schools and to promote market solutions through private schools, vouchers, charters and the like.

Skills and human capital are central to many of the chapters in Vally and Motala’s book, and a critique of neoliberalism forms the context for their analyses. Although the left is often criticised, falsely, for an economic determinism, the book points out how the right, in the discourses above, practices its own version of economic determinism: education leads to skills, skills lead to employment, employment leads to economic growth, economic growth creates jobs and is the way out of poverty and inequality.

The book shows in great detail the failures and disingenuousness of the arguments of the right in casting the blame for education and development problems. Mismatch, human capital and neoliberal discourses first and foremost blame individuals for their lack of “investment” in human capital, for their not attending school, for their dropping out of school, for their not studying the “right” fields, for their lack of entrepreneurship.

The only solution is education

If you hold neoliberal views, the only legitimate solution to the triple challenge is education, other than removing government from any “interference” in the market. That is, if you are a market fundamentalist, it is illegitimate for government to do anything. Neoliberals even look upon government-sponsored education with suspicion; hence the call for privatisation, vouchers, charters, merit pay, and so forth.

But blaming education, as Stephanie Allais and Oliver Nathan say in their chapter, is a “con”, that is, a scam, a ploy. John Treat, in his chapter, quotes Marc Levine: “Put another way, there’s a strong ideological component behind the skills gap [argument]: it diverts attention (and policies) from the deep inequalities and market fundamentalism that created the unemployment crisis, and focuses on a fake skills gap that had nothing to do with the surge in joblessness.”

Human capital theory and neoliberal economics are examples of what has been called “zombie economics”. Treat quotes John Quiggin’s explanation of zombie economics: they are “beliefs about economic policy that have been ‘killed’ by evidence and analysis, but somehow, like ‘zombie ideas’, keep coming back’.”

For the right, the value of education is reduced to economics. This fundamentally contradicts the essence of education, a refrain throughout the book. In fact, the book is dedicated to and opens with a quote from Neville Alexander to this effect and it is worth repeating part of it here: “Once the commodity value of people displaces their intrinsic human worth or dignity, we are well on the way to a state of barbarism.”

A dual system of education

A global view shows how, with capital freely mobile, we are faced with a planetary-wide reserve army of the unemployed and underemployed that keeps wages down, workers insecure and unions weak. In education, everywhere, there are schools for the rich and very different schools for the poor. This is hardly acknowledged, let alone challenged.

Neoliberal capitalism is also racialist capitalism, patriarchal capitalism, plutocratic and monopoly capitalism. The left has been caricatured as having a conspiracy theory understanding of capitalism’s operation and motives. Long ago most of the left rejected the need for a conspiracy. World system structures maintain capitalism, racialism, patriarchy and so on. But I wouldn’t reject the idea of collusion out of hand. What else is the World Economic Forum but a meeting of the global, dare I say, ruling elite in an undemocratic forum to decide on global policies? Nowhere, of course, does the right see the inherent problems in the structure of capitalism nor even recognise neoliberalism. After the fall of the Soviet Union, right-wing books proclaimed the end of history, the end of ideology – we now had the one best system and we just had to tinker with it and wait for prosperity to sweep the globe.

Well, how long are we willing to wait? While millions are suffering and dying and the rich get obscenely rich at the expense of the rest of us? It has become commonplace to recognise that capitalism has increased material production and wealth – even Marx did – but production for whom? Wealth for whom? The most obscene statistic I’ve heard is that the 85 richest individuals on the planet have the same total wealth as the poorest 3.5-billion people on the planet.

Can capitalism be tamed?

Can capitalism be improved, be fair and just? I am not clairvoyant, I can’t see the future. I have liberal, even progressive, colleagues who believe that capitalism can be tamed in the broader social interest.

I wish it were so, but I don’t think so. The greed and inequality promoted by capitalism, the racialism and sexism and environmental destruction that capitalism takes advantage of and promotes are extraordinarily resistant to change. Governments, captured by elites and by the unequal logic inherent in our world system, can only with great difficulty offer significant challenges.

But Education, Economy and Society goes well beyond the failure of current discourses and realities. Throughout, chapter authors consider alternative perspectives and policies that may move us in more progressive directions.

These include the need for and existence of what editors Motala and Vally call “vital and vibrant” social movements to challenge world system structures. Sheri Hamilton situates her chapter on worker education in global movements: anti-globalisation, the Arab Spring, Occupy, the Indignados in Spain, anti-austerity in Europe, strike waves in South Africa – and I would add the earlier anti-apartheid movement in South Africa and the civil rights movement in the US, the women’s movement around the world, the landless movement in Brazil, the Dalit movement in India, and many others.

I teach a course called Alternative Education, Alternative Development, which focuses on what to do from a critical progressive perspective, and I would like to close by adding to the list of alternatives above.

In terms of development:

- We can be inspired by the potential for democratic electoral politics, despite its limits, to bring half a dozen Latin American countries left, progressive governments;

- Even limited gains are valuable. For example, some say South Africa has the most progressive constitution in the world and some say Brazil has the best child legislation in the world. In both cases, they are far from making it a reality, but it still represents progress and can be – and is – a focal point for struggle; and

- We can build on experiments with alternatives to business as usual around the globe in the form of co-operatives, worker ownership and workplace democracy.

In terms of education (I know Latin America better than Africa):

- In Brazil, the Citizen School movement has built a sizeable democratic, participatory, Freirean-based education system in a number of places inside and outside Brazil;

- In Venezuela, Chavez’s Bolivarian Revolution instituted a large-scale Higher Education for All system; and

- In Brazil again, there are the Landless Movement schools, founded by some of the poorest people in the world – often living off agricultural labour, now organised and politically influential – with a large system of very participatory, democratic, Freirean-based schools.

I don’t mean to romanticise any of this. This is a struggle over the long haul and the outcome is uncertain; but, as I said, I am optimistic. I am optimistic because of the examples above. I am also optimistic because I was fortunate enough to attend the World Social Forum in Brazil twice and to march with 100 000 activists from all over the world. I met some of those who are struggling to change the world in areas such as education, health, food, water, environment and development.’-Mail&Guardian

Steven J Klees is professor of international and comparative education at the University of Maryland, US. This is an edited version of the address he will deliver on July 22 at the launch of Education, Economy and Society, co-edited by Salim Vally and Enver Motala and published by Unisa Press

Read more on the devastation, destruction and lies of neoliberalism:

The Destruction of our World and the lies of Milton Friedman

People’s Tragedy: Neoliberal Legacy of Thatcher and Reagan

Selling off our Motherland: The Biggest Crime of the Broken Economic Model

Economic Growth: The Index of Misery

...And now read about the possible paths on how we may put right what has so tragically gone wrong

I am positive and hopeful. We can change the world for the better. Come with me on this journey of self discovery in the interest of the common good

Photo:pinterest.com

Remaking Economics in an age of economic soul-searching

The World would be a Better Place if Economists had Read This Book

In Praise of Darwin Debunking the Self-seeking Economic Man

Brexit, Trump and the failure of our universities to pursue wisdom

Calling all academic economists: What are you teaching your students?

Values-free, Market- Driven Education: What a Disaster!

The Journey to Sophia: Education for Wisdom

Wisdom and the Well-Rounded Life: What Is a University?

My Economics and Business Educators’ Oath: My Promise to My Students

What might an Economy for the Common Good look like?

The Age Of Perpetual Crisis: What are we to do in a world seemingly spinning out of our control?

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 1587

‘The philosopher Adam Smith wasn't the free-market fundamentalist many assume he was. It's time we started reading him properly.’-Amartya Sen

...They have not, and thus, have set the world on fire!

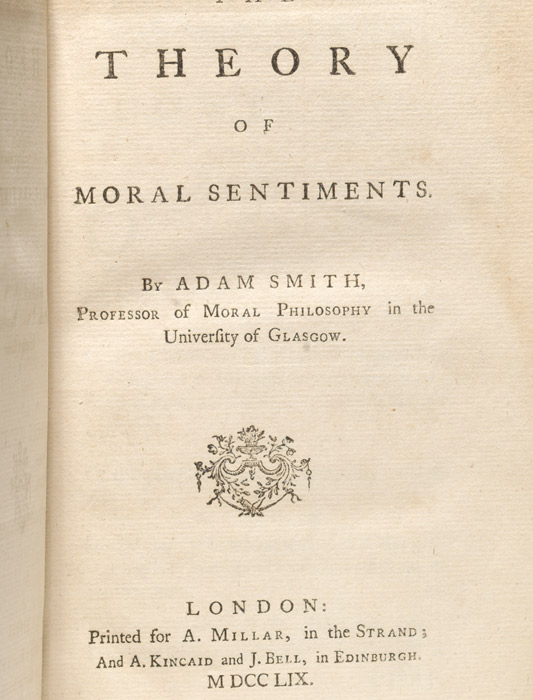

This is the Book that the economists by and large have never read

And this is why, by and large, the discipline is in such a mess, discredited and is not trusted

If they had, then they would, among other issues, would have discovered ‘the appreciation of the demands of rationality, the need for recognising the plurality of human motivations, the connections between ethics and economics, and the codependent rather than free-standing role of institutions in general, and free markets in particular, in the functioning of the economy.’

And moreover, if they had, then, they would have accepted the £1000,000 Donation!!

Ethics boys

'Sir, Around 1991 I offered the London School of Economics a grant of £1 million to set up a Chair in Business Ethics. John Ashworth, at that time the Director of the LSE, encouraged the idea but had to write to me to say, regretfully, that the faculty had rejected the offer as it saw no correlation between ethics and economics. Quite.' Lord Kalms, House of Lords, in a letter to the Times (08/03/2011)

A forgotten book by one of history’s greatest thinkers reveals the surprising connections between economics, virtues, progress, fame, fortune, happiness and joy.

‘The Theory of Moral Sentiments is a global manifesto of profound significance to the interdependent world in which we live.’- Amartya Sen

SMITH, Adam. The Theory of Moral Sentiments. London: Printed for A. Millar, in the Strand; And A. Kincaid and J. Bell, in Edinburgh, 1759.-Photo:baumanrarebooks.com

Nota bene

Where does my economic thinking come from? Who inspires me to say what I say? My economic guru is the real Adam Smith, not the false one taught at universities the world over. Let me explain:

‘As many observers, including some honest economists themselves have noted, the economics profession was arguably the first casualty of the 2008-2009 global financial crises. After all, its practitioners failed to anticipate the calamity, and many appeared unable to say anything useful when the time came to formulate a response.

Mainstream economic models were discredited by the crisis because they simply did not admit of its possibility. Moreover, training that prioritised technique over intuition and theoretical elegance over real-world relevance did not prepare economists to provide the kind of practical policy advice needed in exceptional circumstances.

Some argue that the solution is to return to the simpler economic models of the past, which yielded policy prescriptions that evidently sufficed to prevent comparable crises. Others insist that, on the contrary, effective policies today require increasingly complex models that can more fully capture the chaotic dynamics of the twenty-first-century economy.

Why this debate misses the key point. Because, it was not, and it is not about the models to begin with. It is all about what economics was and what it has become. It is all about the missing values in the so-called modern economics.

As a “Recovered” economist, who has seen the “Light” and hopefully is now wiser than before, I believe I can shed some light on this matter:

‘These days I am inspired by the “Real” and “True” Adam Smith, known the world over as the Father of New Economics. We should recall the wisdom of Adam Smith, who was a great moral philosopher first and foremost. In 1759, sixteen years before his famous Wealth of Nations, he published The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which explored the self-interested nature of man and his ability nevertheless to make moral decisions based on factors other than selfishness. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith laid the early groundwork for economic analysis, but he embedded it in a broader discussion of social justice and the role of government. Today we mainly know only of his analogy of the ‘invisible hand’ and refer to him as defending free markets; whilst ignoring his insight that the pursuit of wealth should not take precedence over social and moral obligations.

We are taught that the free market as a ‘way of life’ appealed to Adam Smith but not that he thought the morality of the market could not be a substitute for morality for society at large. He neither envisioned nor prescribed a capitalist society, but rather a ‘capitalist economy within society, a society held together by communities of non-capitalist and non-market morality’. As it has been noted, morality for Smith included neighbourly love, an obligation to practice justice, a norm of financial support for the government ‘in proportion to [one’s] revenue’, and a tendency in human nature to derive pleasure from the good fortune and happiness of other people.

He observed that lasting happiness is found in tranquillity as opposed to consumption. In their quest for more consumption, people have forgotten about the three virtues Smith observed that best provide for a tranquil lifestyle and overall social well-being: justice, beneficence (the doing of good; active goodness or kindness; charity) and prudence (provident care in the management of resources; economy; frugality).

I am very sorry that, no one taught me these when I was a student of economics, and then, I did not tell the truth about Adam Smith to my students when I became an economics lecturer; something that I very much regret and something that am trying hard to rectify, now that I am a “Recovering and Repenting” economist for the common good. At the end of the day, it is our honesty, humility and our struggle to seek the truth that will set us free and allow us to hold our head high.’...Economics, Globalisation and the Common Good: A Lecture at London School of Economics

Imaging a Better World: Moving forward with the real Adam Smith

Adam Smith and the Pursuit of Happiness

Adam Smith: Architect of the modern world

Re-examining the Relationship Between Ethics and Economics

Photo: trillfilm.com

The 18th-century philosopher Adam Smith wasn’t the free-market fundamentalist he is thought to be!

‘...that there are good ethical and practical grounds for encouraging motives other than self-interest.’- Adam Smith

The economist manifesto

A Reflection by Amartya Sen*

‘The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Adam Smith's first book, was published in early 1759. Smith, then a young professor at the University of Glasgow, had some understandable anxiety about the public reception of the book, which was based on his quite progressive lectures. On 12 April, Smith heard from his friend David Hume in London about how the book was doing. If Smith was, Hume told him, prepared for "the worst", then he must now be given "the melancholy news" that unfortunately "the public seem disposed to applaud [your book] extremely". "It was looked for by the foolish people with some impatience; and the mob of literati are beginning already to be very loud in its praises." This light-hearted intimation of the early success of Smith's first book was followed by serious critical acclaim for what is one of the truly outstanding books in the intellectual history of the world.

After its immediate success, Moral Sentiments went into something of an eclipse from the beginning of the 19th century, and Smith was increasingly seen almost exclusively as the author of his second book, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, which, published in 1776, transformed the subject of economics. The neglect of Moral Sentiments, which lasted through the 19th and 20th centuries, has had two rather unfortunate effects.

First, even though Smith was in many ways the pioneering analyst of the need for impartiality and universality in ethics (Moral Sentimentspreceded the better-known and much more influential contributions of Immanuel Kant, who refers to Smith generously), he has been fairly comprehensively ignored in contemporary ethics and philosophy.

Second, since the ideas presented in The Wealth of Nations have been interpreted largely without reference to the framework already developed in Moral Sentiments (on which Smith draws substantially in the later book), the typical understanding of The Wealth of Nations has been constrained, to the detriment of economics as a subject. The neglect applies, among other issues, to the appreciation of the demands of rationality, the need for recognising the plurality of human motivations, the connections between ethics and economics, and the codependent rather than free-standing role of institutions in general, and free markets in particular, in the functioning of the economy.

Beyond self-love

Smith discussed that to explain the motivation for economic exchange in the market, we do not have to invoke any objective other than the pursuit of self-interest. In the most widely quoted passage from The Wealth of Nations, he wrote: "It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love." In the tradition of interpreting Smith as the guru of selfishness or self-love (as he often called it, not with great admiration), the reading of his writings does not seem to go much beyond those few lines, even though that discussion is addressed only to one very specific issue, namely exchange (rather than distribution or production) and, in particular, the motivation underlying exchange. In the rest of Smith's writings, there are extensive discussions of the role of other motivations that influence human action and behaviour.

Beyond self-love, Smith discussed how the functioning of the economic system in general, and of the market in particular, can be helped enormously by other motives. There are two distinct propositions here. The first is one of epistemology, concerning the fact that human beings are not guided only by self-gain or even prudence. The second is one of practical reason, involving the claim that there are good ethical and practical grounds for encouraging motives other than self-interest, whether in the crude form of self-love or in the refined form of prudence. Indeed, Smith argues that while “prudence” was “of all virtues that which is most helpful to the individual”, “humanity, justice, generosity, and public spirit, are the qualities most useful to others”. These are two distinct points, and, unfortunately, a big part of modern economics gets both of them wrong in interpreting Smith.

The nature of the present economic crisis illustrates very clearly the need for departures from unmitigated and unrestrained self-seeking in order to have a decent society. Even John McCain, the Republican candidate in the 2008 US presidential election, complained constantly in his campaign speeches of “the greed of Wall Street”. Smith had a diagnosis for this: he called such promoters of excessive risk in search of profits “prodigals and projectors” - which, by the way, is quite a good description of many of the entrepreneurs of credit swap insurances and sub-prime mortgages in the recent past.

The term "projector" is used by Smith not in the neutral sense of "one who forms a project", but in the pejorative sense, apparently common from 1616 (or so I gather from The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary), meaning, among other things, "a promoter of bubble companies; a speculator; a cheat". Indeed, Jonathan Swift's unflattering portrait of "projectors" in Gulliver's Travels, published in 1726 (50 years before The Wealth of Nations), corresponds closely to what Smith seems to have had in mind. Relying entirely on an unregulated market economy can result in a dire predicament in which, as Smith writes, "a great part of the capital of the country" is "kept out of the hands which were most likely to make a profitable and advantageous use of it, and thrown into those which were most likely to waste and destroy it".

False diagnoses

The spirited attempt to see Smith as an advocate of pure capitalism, with complete reliance on the market mechanism guided by pure profit motive, is altogether misconceived. Smith never used the term “capitalism” (I have certainly not found an instance). More importantly, he was not aiming to be the great champion of the profit-based market mechanism, nor was he arguing against the importance of economic institutions other than the markets.

Smith was convinced of the necessity of a well-functioning market economy, but not of its sufficiency. He argued powerfully against many false diagnoses of the terrible “commissions” of the market economy, and yet nowhere did he deny that the market economy yields important “omissions”. He rejected market-excluding interventions, but not market-including interventions aimed at doing those important things that the market may leave undone.

Smith saw the task of political economy as the pursuit of “two distinct objects”: “first, to provide a plentiful revenue or subsistence for the people, or more properly to enable them to provide such a revenue or subsistence for themselves; and second, to supply the state or commonwealth with a revenue sufficient for the public services”. He defended such public services as free education and poverty relief, while demanding greater freedom for the indigent who receives support than the rather punitive Poor Laws of his day permitted. Beyond his attention to the components and responsibilities of a well-functioning market system (such as the role of accountability and trust), he was deeply concerned about the inequality and poverty that might remain in an otherwise successful market economy. Even in dealing with regulations that restrain the markets, Smith additionally acknowledged the importance of interventions on behalf of the poor and the underdogs of society. At one stage, he gives a formula of disarming simplicity: “When the regulation, therefore, is in favour of the workmen, it is always just and equitable; but it is sometimes otherwise when in favour of the masters.” Smith was both a proponent of a plural institutional structure and a champion of social values that transcend the profit motive, in principle as well as in actual reach.

Smith’s personal sentiments are also relevant here. He argued that our “first perceptions” of right and wrong “cannot be the object of reason, but of immediate sense and feeling”. Even though our first perceptions may change in response to critical examination (as Smith also noted), these perceptions can still give us interesting clues about our inclinations and emotional predispositions.

One of the striking features of Smith's personality is his inclination to be as inclusive as possible, not only locally but also globally. He does acknowledge that we may have special obligations to our neighbours, but the reach of our concern must ultimately transcend that confinement. To this I want to add the understanding that Smith's ethical inclusiveness is matched by a strong inclination to see people everywhere as being essentially similar. There is something quite remarkable in the ease with which Smith rides over barriers of class, gender, race and nationality to see human beings with a presumed equality of potential, and without any innate difference in talents and abilities.

He emphasised the class-related neglect of human talents through the lack of education and the unimaginative nature of the work that many members of the working classes are forced to do by economic circumstances. Class divisions, Smith argued, reflect this inequality of opportunity, rather than indicating differences of inborn talents and abilities.

Global reach

The presumption of the similarity of intrinsic talents is accepted by Smith not only within nations but also across the boundaries of states and cultures, as is clear from what he says in both Moral Sentiments and The Wealth of Nations. The assumption that people of certain races or regions were inferior, which had quite a hold on the minds of many of his contemporaries, is completely absent from Smith's writings. And he does not address these points only abstractly. For example, he discusses why he thinks Chinese and Indian producers do not differ in terms of productive ability from Europeans, even though their institutions may hinder them.

He is inclined to see the relative backwardness of African economic progress in terms of the continent’s geographical disadvantages - it has nothing like the “gulfs of Arabia, Persia, India, Bengal, and Siam, in Asia” that provide opportunities for trade with other people. At one stage, Smith bursts into undisguised wrath: “There is not a negro from the coast of Africa who does not, in this respect, possess a degree of magnanimity which the soul of his sordid master is too often scarce capable of conceiving.”

The global reach of Smith’s moral and political reasoning is quite a distinctive feature of his thought, but it is strongly supplemented by his belief that all human beings are born with similar potential and, most importantly for policymaking, that the inequalities in the world reflect socially generated, rather than natural, disparities.

There is a vision here that has a remarkably current ring. The continuing global relevance of Smith's ideas is quite astonishing, and it is a tribute to the power of his mind that this global vision is so forcefully presented by someone who, a quarter of a millennium ago, lived most of his life in considerable seclusion in a tiny coastal Scottish town. Smith's analyses and explorations are of critical importance for any society in the world in which issues of morals, politics and economics receive attention. The Theory of Moral Sentiments is a global manifesto of profound significance to the interdependent world in which we live.’- Amartya Sen, The economist manifesto

Read More:

A Must Read Book about how Adam Smith can change your life for better

My Economics and Business Educators’ Oath: My Promise to My Students

The Age Of Perpetual Crisis: What are we to do in a world seemingly spinning out of our control?

- A Must Read Book about how Adam Smith can change your life for better

- Austerity driven Homeless children put up in Shipping Containers in ‘Great Britain’

- In Praise of Darwin Debunking the Self-seeking Economic Man

- American Dream was False and is Dead. But, the Good American Dream Can be Resurrected

- In Praise of Youth on International Youth Day- Monday 12 August 2019