- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 6112

The Republic Of Hunger

Facts:

“Every third malnourished child in the world is from India.

More than 40 per cent of India's 61 million children are malnourished.

Malnutrition, classroom hunger and school dropout rates continue to be grave, giving rise to extreme poverty and hunger.

47% of those under three years old are undernourished and underweight

Measured by the prevalence of malnutrition, India is doing worse than sub-Saharan Africa.

In recent years the GDP has grown at nearly 10% each year.

By 2011 there were 57 billionaires in India.”

India’s Premier Manmohan Singh called this malnutrition, hunger and poverty “a national shame”. The Premier then noted that “We cannot hope for a healthy future with a large number of malnourished children”.

Dr. Manmohan Singh’s worries and concerns are noted and appreciated. But, here we need to be more precise, if we wish to move away from hollow words to real action, which is surely needed if countries such as India wish to eradicate poverty, hunger and malnutrition. Dr. Singh’s reputation was forged in his time as finance minister in the 1990s, when following the advice of International Monetary Fund he pushed through a series of economic liberalisation and reforms which set the stage for India's subsequent boom and entry onto the world stage as a rising economic power.

The Questions:

Given the above, one might, with much justification, ask what have been the fruits of the decades of embracing neo-liberalism, with is privatisation, liberalisation, deregulation, marketisation and more? What is the use of India boasting the rise of millionaires and billionaires, the high-tech industries and more, when a huge percentage of its children are hungry, malnourished, and underweight? Where is the trickle-down effect? 10% average GDP growth rate for what? What has happened to Indian spirituality, looking after the community and the common good?

Dr. Singh once said: "The greatness of democracy is that we are all birds of passage. We are here today, gone tomorrow. But in the brief time that the people entrust us with this responsibility it is our duty to be honest and sincere in the discharge of these responsibilities."

I very much wonder how he can reconcile the above statement with so much continuing and worsening poverty, hunger, and malnutrition in India.

I very much recommend you to watch this informative video:

The Republic Of Hunger

http://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/101east/2012/05/201251010473237279.html#.T69J2A_f4jE.gmail

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 8770

“Socialism never took root in America because the poor see themselves not as an exploited proletariat but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires.” —John Steinbeck

But, then, America has always been at its best, most efficient, when guided by socialist principles

In an article in the Financial Times ( 31 May 2015) Edward Luce remarks that:

“To most students of US politics, the phrase American socialism is an oxymoron — like clean coal or the Bolivian navy. A century ago, Werner Sombart, a German scholar, asked “Why is there no socialism in America?” It was a question that confounded Marxists. As the most advanced capitalistic society, the US was most ripe for a proletarian revolution, according to their teleology.”

Then, Luce notes that today’s America is different:

“Leftwing politicians are in electoral retreat across most of the western world. The one exception is the United States. At 15 per cent in the Democratic polls, Bernie Sanders, the senator from Vermont, is riding higher than any US socialist since Eugene Debs ran for the White House a century ago.

The fact that Mr Sanders has very little chance of unseating Hillary Clinton is beside the point. His popularity is dragging her leftward. If he flames out, other left-wingers, such as Martin O’Malley, the former governor of Maryland who entered the race at the weekend, are ready to pick up the baton. Elizabeth Warren, the populist Massachusetts senator, will continue to prod Mrs Clinton from outside the field. The more Mrs Clinton adopts their language, the harder it will be for her to reclaim the centre ground next year. Yet she is only following the crowd. A surprisingly large chunk of Democrats are happy to break the US taboo against socialism.”

I very much agree with Luce. For me, America has always had a socialist economy, at its best, most efficient, when guided by socialist principles. Now, it should also try a bit harder and create a more equality, harmony, justice and well-being for more Americans. "American Dream" can only be realised when it serves the common good.

See below for more:

Face it, the US economy is socialist

“Once you accept the fact that some kind of socialism is part of the US economy, we no longer have to suffer silly debates over whether it is or it not partly socialist. It is.”

…“ By this standard, the US is a socialist country, because to some degree or another, the government has always got involved in the economy: the railroads, the Homestead Act, the power grid, the interstate highway system, and the internet. These are products of the government creating markets or meeting demand, and then getting out of the way to allow capitalism to work. Most in the US wouldn't call this socialism, however. They would call it good governance.

That the US has shepherded the economy in one way or another exemplifies its economy's mixed nature. It's mostly capitalist, but partly socialist when the profit-motive is detrimental to human need. The best example is Medicare. The older you are, the less insurable you are. In a free market, in which government coercion is completely absent from the exchange of commodities and securities, the elderly would die sooner. That's how markets work, and that's why Lyndon Johnson didn't want the elderly to be at the mercy of the markets.”…

Face it, the US economy is socialist - Al Jazeera English

For further reading see:

Socialism and the Common Good: New Fabian Essays (Paperback) - Taylor & Francis

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 8773

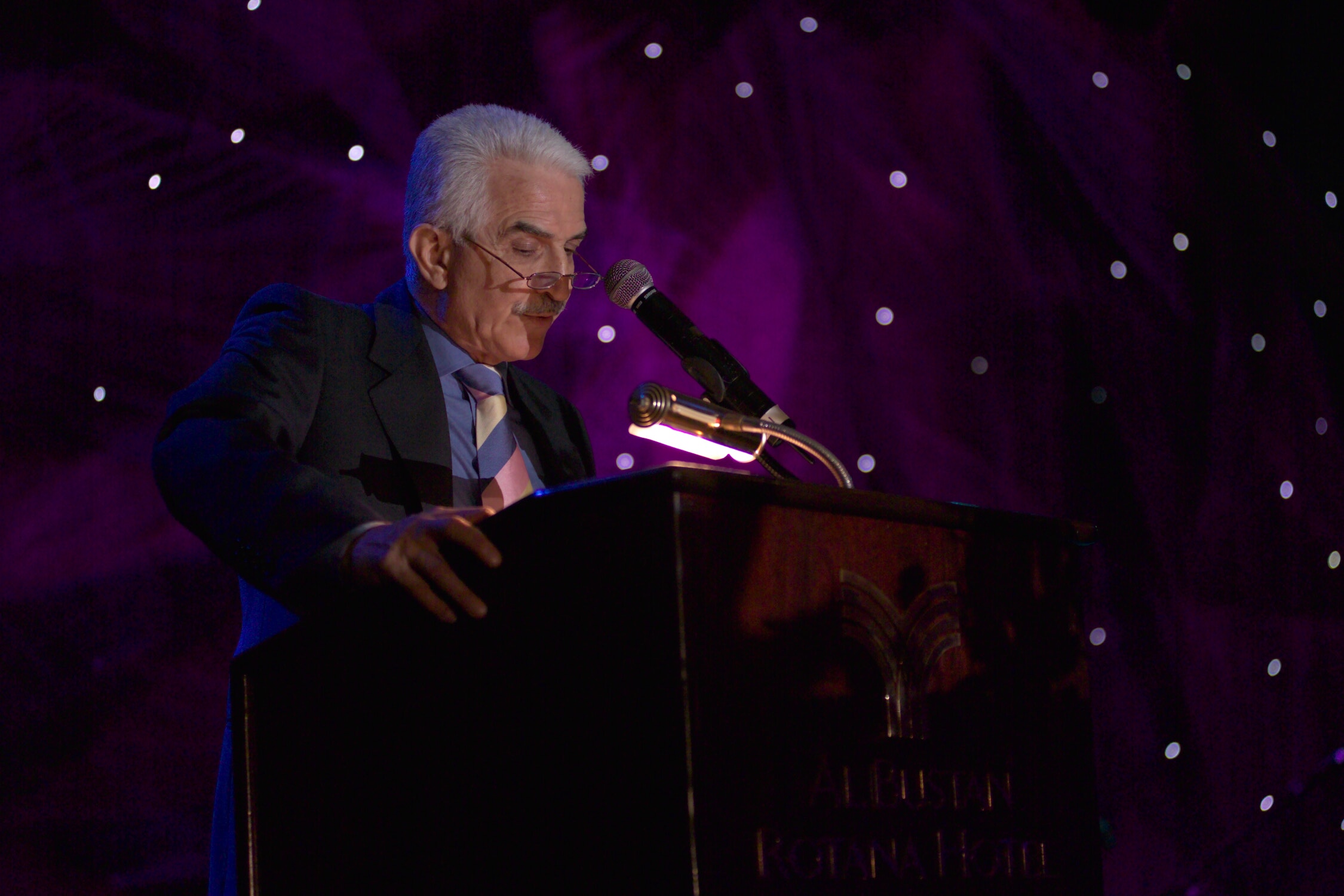

While I was re-visiting some old documents, to prepare a booklet on the GCGI’s Conference Series 10th Anniversary (2002-2012), I came across the text of a keynote speech I had given at the 3rd Annual GCGI Conference in Dubai in March 2004. The speech was delivered at a Special Session, “Iran and Globalisation for the Common Good”, organised by the Iranian Business Council, (IBC), Dubai, during the Gala Dinner on the evening of Sunday, 28th March.

It was a very memorable occasion: Around 500 invited guests, amongst them, senior politicians, diplomats, business, cultural and military attaches, captains of industry, bankers and financial leaders, the leaders of the civil societies, NGOs and the media, senior religious and spiritual representative, scholars, researchers, students, youth and many more.

Given the current state of the world economy, the crises and challenges of capitalism, and more, I think recalling and remembering this speech- delivered over 9 years ago, at the height of the hyper boom and the seemingly unstoppable march of neo-liberalism and economic-globalisation, may prove to be very telling.

The encounter and dialogue that I had with so many senior global leaders in Dubai in 2004, and reflecting on what was said, may assist us to shed some light on what has gone wrong with capitalism and globalisation and why, as well as what might be needed to guide us all to a better world.

The 3rd Annual International Conference on An Inter-faith Perspective on Globalisation for the Common Good

The Middle East and Globalisation for the Common Good, 26-31 March 2004, Dubai

-Special Session- Sunday, 28th March, 2004

“Iran and Globalisation for the Common Good”

Organised by the Iranian Business Council, (IBC), Dubai

Under the Patronage of H.H. Sheikh Hamdan Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Deputy Ruler of Dubai and Minister of Finance

Text of the Keynote Speech by Kamran Mofid, PhD (Econ)

Founder, An Inter-faith Perspective on Globalisation for the Common Good

“A Businessman and an Economist in Dialogue for the Common Good”

|

|

| Kamran Mofid | Abbas Bolurfrushan |

Your Highness, Your Excellencies, Honourable IBC members, distinguished guests, speakers and delegates of the 3rd International Conference on an Inter-faith Perspective on Globalisation for the Common Good, friends, colleagues, ladies and gentlemen:

Tonight I am very conscious of the fact that we are blessed with two senior scholars and researchers who will be speaking after me. Given this, I am not going to present to you a formal paper in an academic sense. What I am going to do is to tell you a light-hearted story. A story of” when Kamran met Abbas (Mr. Abbas Bolurfrushan, President, IBC, Dubai) for the common good”.

The story in turn will introduce you to the concept of Globalisation for the Common Good and why we need it and also why and how this wonderful event came into being.

I came to Dubai first about sixteen months ago. I had a wonderful reception, had a few meetings and enjoyed thoroughly the hospitality of this beautiful land. However, although I am conscious that this was my first visit to Dubai, I did not succeed in making any inroads for Globalisation for the Common Good. A few weeks after my return home my fellow traveller for the common good and a resident of Dubai, namely, Dr. Raymond Hamden, phoned me with excitement that he has met the President of the IBC and he thinks that I should meet with him in the near future, as he believes in Mr. Bolurfrushan there might be a friend for Globalisation for the Common Good. Thus, I returned to Dubai to meet with Mr. Bolurfrushan. Below is a summary of our meeting.

“Good Morning, Dr. Mofid. Welcome to Dubai and the IBC. Hope all is well with you. I hear you are promoting Economics of Compassion as well as Globalisation for the Common Good. I must admit, I am very much intrigued by this, especially as I know you are an economist, and I want to hear more about these issues.”

“Thank you very much Mr. Bolurfrushan for your kind words of welcome. With your permission, before I try to discuss Globalisation for the Common Good, I would like to make a couple of statements”.

Today the globalised world economy, despite many significant achievements during the last few decades, and especially since the end of the Second World War, in areas such as science, technology, medicine, transportation and communication, is facing major catastrophic socio-economic, political, cultural and environmental crises.

We are surrounded by global problems of inequality, injustice, poverty, greed, marginalisation, exclusion, intolerance, fear, mistrust, xenophobia, terrorism, sleaze and corruption. These problems are affecting the overall fabric of societies and comunities in many parts of the world.

Moreover, the twentieth century was the bloodiest in human history, with holocausts, genocides, ethnic cleansing, two world wars and hundreds of inter and intra-national wars. Furthermore, today after decades of selfishness, greed, individualism, emphasis on wealth creation without care about how this wealth is being created, the world is entering a period of reflection, self-examination and spiritual revolution. Many people around the globe have come to an understanding that it is possible to create a better world if a critical mass of people with a sense of human decency and a belief in the ultimate goodness of humanity, rise and realise their power to transform the world. More and more people around the world are realising that there are no short cuts to happiness. Material wealth is important. This should not be denied. However, physical wealth is only one ingredient for happiness. Realisation of a complete sense of happiness, inner peace and tranquillity can only be achieved through acting more on virtues such as wisdom, justice, ethics, love and humanity. This spiritual revolution needs architecture and dedicated architects. I do hope that IBC under your leadership, will be able to assist us to articulate, construct and promote this vision and the necessary required course of action.

Having shared the above dialogue with Mr. Bolurfrushan on the need for compassion and spirituality in the course of globalisation, I then engaged myself with him on the shortcomings of current economic globalisation which as it seems has no respect for other human values. Below is the gist of my dialogue with him.

Today’s financial globalisation, of which we hear so much, has created an environment and culture in which individual self-interest takes priority over social good. A transactional view of the world dominates economic thinking; personal relationships and the creation of a stable society are largely ignored in the maximisation of profits. Economic globalisation without a globalisation of compassion for the common good, is nothing but a ‘house of cards’, ready to be blown away by forces that ultimately it would not be able to control. The historian Arnold Toynbee, who traced the rise and fall of civilisations, asserted that spirituality was more significant than political leaders in the rise of civilisations, and that once a civilisation lost its spiritual core it sank into decline. May I add that, I hope this be a lesson to those who believe that they can create and control civilisations through the use of brutal and inhumane force.

Another major shortcoming of economic globalisation is its slavish adherence to market forces. This is wrong and harmful as it has removed human beings from the equation. If everything can be done according to market forces, then where is the place for us, for humanity, for love and compassion?

The 1987 Nobel Prize Laureate in Economics, Professor Robert Solow made the following wise remark about the over-emphasis on market forces and competition. “Few markets can ever have been as competitive as those that flourished in Britain in the first half of the nineteenth century, when infants became deformed as they toiled their way to an early death in the pits and mills of the Black Country. And there is no lack of examples today to confirm the fact also that well-functioning markets have no innate tendency to promote excellence in any form. They offer no resistance to forces making for a descent into cultural barbarity or moral depravity”.

Having discussed the above with Mr. Bolurfrushan, I thought that I have to demonstrate to him that I am not a negative observer, criticising all, being against everything and not having an alternative model in mind myself. Therefore, I presented to him my second statement as below:

As an economist with a wide range of experience, I do appreciate the significance of economics, politics, trade, banking, insurance and commerce, and of globalisation. I understand the importance of wealth creation. But wealth must be created for the right reasons. I want to have a dialogue with the business community. I want to listen to them and be listened to. Today’s business leaders are in a unique position to influence what happens in society for years to come. With this power comes monumental responsibility. They can choose to ignore this responsibility, and thereby exacerbate problems such as economic inequality, environmental degradation and social injustice, but this will compromise their ability to do business in the long run. The world of good business needs a peaceful and just world in which to operate and prosper.

However, in order to arrive at this peaceful and prosperous destination, we need to change the house of neo-classical economics, to make a fit home for the common good. After all, many of the issues that people struggle over, or their governments put forward, have ultimately economics at their core. As I mentioned before, the creation of a stable society in today’s global world is largely ignored in favour of economic considerations of minimising costs and maximising profits, while other equally important values are put aside and ignored.

John Maynard Keynes predicted a moment when people in advanced economies would step back from traditional economic imperatives and feel free to concentrate on how to live wisely, agreeably and well. The purpose of the economy, according to Keynes, is to control the material basis of a civilised society, enabling its citizens to explore the higher dimensions of human existence, to discover their own full potential. In our world of prosperity for the few, we seem to have got that backwards. Lives are restricted by harsh working conditions and the common assets of a community are degraded in the pursuit of endless economic growth.

Economics once again must find its heart, soul and spirituality. Moreover, it should also reconnect itself with its original source, rooted in ethics and morality. Today’s huge controversy which surrounds much of the economic and business world is because they do not adequately and appropriately address the needs of the global collective and the powerless, marginalised and excluded. This, surely, in the interest of all, has to change. The need for an explicit acknowledgment of true global values, such as altruism, inclusion, universality, fraternity, sympathy, empathy, sharing, security, envisioning, enabling, empowering, solidarity and much more, is the essential requirement in making economics work for the common good. Economics, as practiced today. cannot claim to be for the common good. In short, a revolution in values is needed, when it demands that economics and business must both embrace material and spiritual values simultaneously.

As it can be seen, given the state of our world today, the world of progress and poverty, elaborate, difficult to comprehend, infused by so much mathematical jargon, economic models and theories, has not delivered the happiness that has been promised because of its failure to satisfy people’s spiritual needs. We have to reverse this. Do not let us carry on constructing a global society that is materially rich but spiritually poor. Let us begin to construct globalisation for the common good.

O, I wish you were there to see Mr. Bolurfrushan’s face! I thought that he was happy because of what he had heard already. He seemed to me very eager to carry on our dialogue. He then said: “Dr. Mofid, so far, so good. I think I understand what you are trying to say and the reasons beyond your proposal for economics of compassion, spirituality and the common good. Now please, if you would, try to explain to me and give me your definition of Globalisation for the Common Good.” Below is the gist of what I shared with him during this stage of our conversation.

I began by saying that, the heart and the soul of the concept of the common good is service to others. “Love your neighbour as yourself”. Moreover, the most important ingredients of common good are truth, justice and love. Furthermore, the best way to fulfil our obligations of justice and love is to contribute to the common good and to serve it.

As for defining Globalisation for the Common Good, a globalisation for the common good, is an economy of sharing and is an economy of community. It is not an economy or a system in which well-placed people, institutions or governments can make a ‘killing’. It is an economy and a philosophy whose aim is generosity and the promotion of a just distribution of God’s gifts.

In seeking globalisation for the common good, we, the peoples of the world, could together undertake a healing journey, moving from conflict to harmony, achieving the common good in our global home. The economic vision in globalisation for the common good is the development of globalisation as if people mattered, involving an honest debate on an analysis of integrity, responsibility, accountability and spirituality for the good of all. In short, economic efficiency and compassion as well as justice should work hand in hand to create a humane and peaceful environment for all God’s people.

Globalisation for the common good will ensure the success of globalisation because it will remember that the market place is not only a place of trade; it is also a region for the human spirit, for love and compassion. The practice of business and formulation of economics is generally carried out with little or no reference to spiritual concerns. My own recent work has focused on the need to re-introduce these values into the world of commerce. I have realised, after twenty-five years of teaching economics, that only a spiritually and philosophically committed mind will strive for humane globalisation, for ethical as well as corporate social responsibility. If there is no humanity and spirituality, no love, then the laws enforcing business ethics and corporate responsibility will be broken in the selfish interests of profit-seeking, by the few, for the few. Globalisation for the common good is all about commitment and hope. It is a challenge for hearts and minds. It meets bad ideas with better ones, disadvantage with imagination and vision.

Globalisation for the common good will enable us to discover the urgent need for a new global ‘Bottom Line’. It will help us to acknowledge that the new bottom line must not be all about economic and monetary targets, profit maximisation and cost minimisation, but it should involve spiritual, social and environmental consideration. When practiced under these values, then, the business is real, viable, sustainable, efficient and profitable.

Therefore, the New Bottom Line that you should now believe in must read as follow:

Corporations, business leaders, politicians, government policies, our educational, legal and health care practices, environmental considerations, every institution, law, social policy and even our private behaviour and relationships, should be judged 'rational', 'efficient', or 'productive' not only to the extent that they maximise money and power (The Old Bottom Line) but ALSO to the extent that they maximise love and caring, kindness and generosity, ethical and ecological behaviour, and contribute to our capacity to respond with awe, wonder and radical amazement at the grandeur and mystery of the universe and all being.

Globalisation for the common good empowers us with humanity, spirituality and love. It will raise us above pessimism to an ultimate optimism; turning from darkness to light; from night to day; from winter to spring. This spiritual ground for hope at this time of wanton destruction of our world, can help us recognise the ultimate purpose of life and of our journey in this world.

I then said to Mr. Bolurfrushan that when I realised the shortcomings of the economic models and theories that I had learned in the West, I turned to my original Eastern mysticism and spirituality for help. I started again to read Persian poetry and philosophy. I then recited the following two poems to him which I explained will in turn explain my thoughts on the common good.

The first poem is by Rumi:

What is to be done, O Moslems? For I do not recognise myself.

I am neither Christian, nor Jew, nor Gabr, nor Moslem.

I am not of the East, nor of the West, nor of the land, nor of the sea;

I am not of Nature’s mint, nor of the circling heaven.

I am not of earth, nor of water, nor of air, nor of fire;

I am not of the empyrean, nor of the dust, nor of existence, nor of entity.

I am not of India, nor of China, nor of Bulgaria, nor of Saqsin;

I am not of the kingdom of ’Iraqian, nor of the country of Khorasan.

I am not of this world, nor of the next, nor of Paradise, nor of Hell.

I am not of Adam, nor of Eve, nor of Eden and Rizwan.

My place is the Placeless, my trace is the Traceless;

’Tis neither body nor soul, for I belong to the soul of the Beloved.

I have put duality away, I have seen that the two worlds are one;

One I seek, One I know, One I see, One I call.

He is the first, He is the last, He is the outward, He is the inward;

I am intoxicated with Love’s cup, the two worlds have passed out of my ken;

If once in my life I spent a moment without thee,

From that time and from that hour I repent of my life.

If once in this world I win a moment with thee,

I will trample on both worlds, I will dance in triumph for ever.

The second poem is by Sa’di:

Human beings are like parts of a body

Created from the same essence

When one part is hurt and in pain,

The others cannot remain in peace and be quiet.

If the misery of others leaves you indifferent

And with no feelings of sorrow,

You cannot be called a human being.

I could see a sense of happiness and gratitude in Mr. Bolurfrushan’s face. He mentioned that he had very much enjoyed our conversation and wanted to know how we could achieve Globalisation for the Common Good. I mentioned to him that the first and the most important pre-requisite for globalisation for the common good is to make ourselves, each one of us, fit for the common good. Below is what I shared with him on how this can be achieved:

If we truly want to change the world for the better, all of us, the business community, politicians, workers, men and women, young and old, must truly become better ourselves. We must share a common understanding of the potential for each one of us to become self-directed, empowered and active in defining this time in the world as an opportunity for positive change and healing. We can achieve a culture of peace by giving thanks, spreading joy, sharing love and understanding, seeing miracles, discovering goodness, embracing kindness and forgiveness, practicing patience, teaching tolerance, encouraging laughter, celebrating and respecting the diversity of cultures and religions and peacefully resolving conflicts. We must each of us become an instrument of peace.

In short, in the words of Mahatma Gandhi, we should declare ourselves against the ‘Seven Social Sins’. These are:

Politics without principles

Commerce without morality

Wealth without work

Education without character

Science without humanity

Pleasure without conscience

Worship without sacrifice.

Moreover, in the words of Robert Muller, former UN Under-Secretary General, we ought:

• To see the world with global eyes;

• To love the world with a global heart;

• To understand the world with a global mind;

• To merge with the world with a global spirit.

We can achieve this by:

bringing the material consumption of our species into balance with the needs of the earth;

realigning our economic priorities so that all persons have access to an adequate and meaningful means of

earning a living for themselves and their families;

democratising our institutions to route power to people and communities;

replacing the dominant culture of materialism with cultures grounded in life-affirming values of cooperation,

caring, compassion and community;

integrating the material and spiritual aspects of our beings so that we become whole persons.

I told to Mr. Bolurfrushan that I had completed my presentation to him. He in turn replied that, having heard me, he fully understood what globalisation for the common good is, and the fact that the world desperately needs to know, to understand and to implement this concept. He declared himself for globalisation for the common good and mentioned that he would consult his Board of Directors and seek their support to ensure that more people will hear my message. That’s why I believe we are all here tonight and I thank Mr. Bolurfrushan, the Board of Directors and the entire IBC membership for making this event possible.

Thank you very much ladies and gentlemen, and God Bless you.

GCGI Dubai Conference Final Programme

N.B The above is what I had said in 2004. But, what about today? What can I say now? What can I suggest and offer? Can it be different to what I had said all those years ago in Dubai? Or can it only be inspired by the spirit of my speech, my ideas and vision, as expressed in 2004? Let us discover:

What might an Economy for the Common Good look like?

First published on 15 October 2014

At a recent seminar I was asked by one of the participants if I could explain, in simple, jargon-free language, what I meant by “an economy that serves the common good”, and also what I meant by “sustainability, social justice and ecology”.

I was excited by these questions, as they are very close to my heart. Although, I have written extensively on these issues*, here, now was my chance to engage, face-to-face, with some interested and well-informed people, who wanted some clear explanations. Thus, I began to explain and the dialogue started:

First, I said, in order to see what an economy for the common good might look like, it would be helpful to consider what globalisation for the common good might look like. This is important, as an economy for the common good needs a fertile ground in which to develop. Thus, I began telling them about the Globalisation for the Common Good Initiative (GCGI), where we connect our intellect with our humanity on our path towards the common good...

Continue reading:

What might an Economy for the Common Good look like?

Read a summary about the GCGI in Persian

دربارۀ جهانی سازی اقدام در جهت خیر عامّ *

نوشتۀ کامران مفید

جهانی سازی اقدام در جهت خیر عامّ: جایی که ما عقل و انسانیت خود را به هم پیوند می دهیم

کالج پلِیت، آکسفرد (2002)؛ سنت پترزبورگ، روسیه (2003)؛ دُبِی، امارت متحدۀ عرب (2004)؛ نایروبی و کریچو، کنیا (2005)؛ دانشگاه چامینیِد، هانالولو، هاوایی، ایالات متحدۀ آمریکا (2006)؛ دانشگاه فاتح، استانبول، ترکیه (2007)؛ ترینیتی کالج، دانشگاه ملبورن، استرالیا (2008)؛ دانشگاه لویولا، شیکاگو، ایالات متحدۀ آمریکا (2009)؛ دانشگاه لوتری کالیفرنیا، توزند اوکز، کالیفرنیا، ایالات متحدۀ آمریکا (2010)؛ بیبلیوتکا الکزاندریا، اسکندریه، مصر (2011ـ به سبب انقلاب در مصر به تعویق افتاد)؛ مدرسۀ علوم اقتصادی، پردیس آکسفرد، دانشگاه واتربری هاوس، آکسفرد، بریتانیا (212)؛ دانشگاه بین المللی شهر؛ پاریس، فرانسه (2013)؛ و مدرسۀ علوم سیاسی، پردیس آکسفرد، واتربری هاوس، آکسفرد، بریتانیا (2014).

برای آنکه چالش های دنیای معاصر را بشناسیم، به کنه آنها پی ببریم و با آنها مواجه شویم مقتضی است که توجه خود را بر تصویر جامعی از زندگی متمرکز کنیم. مسأله چه جنگ باشد چه صلح، چه اقتصاد باشد چه محیط زیست، چه عدالت چه بی عدالتی، عشق و نفرت، همکاری و رقابت، خیر خواهی و خودخواهی، علم و فنّاوری، ترقی و فقر، سود و زیان، غذا و جمعیت، انرژی و آب، بیماری و تندرستی، و تعلیم و تربیت و خانواده، ما به این تصویر جامع نیاز داریم تا بتوانیم انبوه مسائل حادّ را، چه بزرگ چه خُرد، چه محلی چه جهانی، تشخیص دهیم و آنها را حلّ کنیم.

آن "تصویر جامع" چارچوبه یا بافتی است که در متن آن ما می توانیم به مؤثرترین نحو پرسش های بزرگ و دیرپای زندگی – یعنی، مقصود و معنا، محاسن و ارزش های آن ـ را جست و جو کنیم.

برای آنکه توجه خود را بر این تصویر جامع متمرکز کنیم وبه هدایت اصول سخت کوشی، تعهد، خدمات داوطلبانه قدم پیش نهیم، در کنفرانسی بین المللی در آکسفرد در سال 2002، با انگیزۀ شوق و شوری برای گفتگوی فرهنگ ها، تمدن ها، ادیان، آراء و دیدگاه ها، نهاد جهانی سازی اقدام برای خیر عامّ و سلسله همایش های بین المللی بنیان نهاده شد.

ما بر این امر واقفیم که مسائل اجتماعی-اقثصادی با مسائل روحی/معنوی ما پیوند تنگاتنگ دارد. به علاوه، عدالت اجتماعی-اقتصادی، صلح و توازن تنها زمانی به دست می آید که ارتباط بنیادین میان جنبه های روحی و عملی زندگی ارزیابی شود. امر لازم برای چنین حرکتی این است که خیر همگان را مشخص کرده، آن راتقویت و حمایت نماییم و به خاطر آن زندگی کنیم. اصل خیر همگان خاطر نشان ما می کند که ما واقعاً مسؤل یکدیگریم- ما نگهبانان برادران و خواهران خودیم ـ و باید اطمینان حاصل کنیم که هر کس و هر گروهی در اجتماع قادر به رفع نیازهای خود و به فعلیّت درآوردن استعداد های خود باشد. نتیجه آنکه هر گروهی در جامعه باید حقوق و آرمان های گروه های دیگر و سعادت کلّ خانوادۀ بشریت را به حساب آورد.

یکی از بزرگ ترین چالش های عصر ما کاربردِ آراء و نظرات مربوط به خیر عامّ در مورد مسائل عملی و یافتن راه حلّ های عامّ است. تبدیل نظرات فلاسفه، علمای دین و رهبران به صورت توافق و همسویی میان سیاست گذاران و ملت ها وظیفۀ دولتمردان و شهروندان است: چالشی که جهانی سازی اقدام برای خیرِ عامّ از آن حمایت می کند. غرض این نیست که فقط دربارۀ خیر عامّ حرف بزنیم یا صرفاً گفتگو کنیم، بلکه منظور این است که دست به اقدام بزنیم، خیر عامّ و گفتگو را برای همه عملی سازیم تا به همۀ ما سود برساند.

چیزی که نهاد جهانی سازی ِ اقدام در جهت خیر عامّ – از طریق برنامه های علمی و پژوهشی و نیز طرح های امداد رسانی و گفتگو های خود - به دنبال عرضۀ آن است، نگرشی است که تلاش برای دستیابی به عدالت اقتصادی و اجتماعی، صلح و ثداوم وثبات محیط زیست را در چارچوب یک آگاهی معنوی و شیوۀ گشاده دستی، سخاوتمندی و شفقت نسبت به دیگران قرار می دهد. بنابراین همگان به انگیزۀ این نگرش و آگاهی تشویق می شوند که در جهت خیر و سعادت عامّه خدمت کنند.

نهاد جهانی سازی ِ اقدام در جهت خیر عامّ از همان آغاز کار از ما خواسته که فراتر از کشمکش ها و سردرگمی های ِ یک زندگی پُرمشغلۀ اقتصادی و مادّیگرایانه به سوی زندگی معناداری سرشار از امید و شادی، حق شناسی، رحم و شفقت حرکت کنیم و برای خیر و صلاح همه خدمت نماییم.

شاید بزرگ ترین توفیق ما در این بوده که توانسته ایم جهانی سازی اقدام در جهت خیر عامّ را به زبان و آگاهی ِ مشترک خیل عظیم تری از مردم درآوریم و در امتداد آن، بحث و گفتگوی لازم را دربارۀ معنا و قابلیت این طرح در زندگی فردی و جمعی خود شروع کنیم.

خلاصه، ما دست اندرکاران جهانی سازی اقدام در جهت خیر عامّ شکرگزاریم که، با در نظر گرفتن اهداف و مقاصدی که از 2002 تا کنون مشعلدار آن بوده ایم ، از آن نگرش و تصور دنیایی بهتر حمایت کرده ایم. بدین خاطر از دوستان و حامیان خود که این طرح را ممکن ساخته اند، بسیار تشکر می کنیم .

*کامران مفید، بنیانگذار این نهاد و مولف کتاب « یک دید بین الادیانی در باره ی جهانی شدن برای خیر عام» مدرک دکتری خود را در رشته ی اقتصاد از دانشگاه بیرمینگهام در انگلستان در سال 1986 به دست آورد.در سال 2001 گواهینامه ی تدریس در مطالعات دینی را از کالج پلاتر ( Plater ) در آکسفورد کسب کرد.

آثار دکتر مفید در باره ی موضوعات مختلف از جمله اقتصاد، سیاست ، روابط بین الملل،الهیات، فرهنگ، محیط زیست و معنویت می باشد.مقالات او در تعدادی از بهترین نشریات علمی و فرهنگی و مجلات و روزنامه ها چاپ شده است.آخرین کتاب وی « پیشبرد خیر عام: نزدیک سازی مجدد اقتصاد و الهیات، گفتگوی یک اقتصاد دان و یک الاهی دان» با همکاری کشیش مارکوس برای بروک نوشته شده است و توسط انتشارات شیفرد والوین در ژوئن 2005 در لندن به چاپ رسیده است.

I am grateful to Dr. Majdoddin Keyvani for translating the original document (About ) from English to Persian