- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 3981

A series of unfortunate events

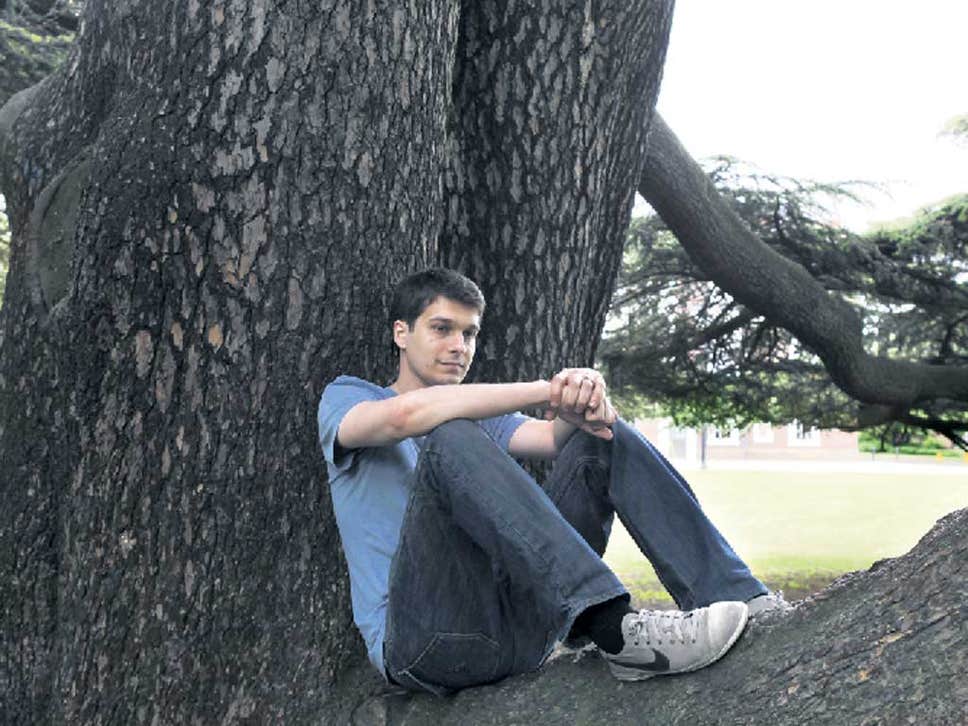

Just four years ago, Chris Nichols had an easy life. But only now, after two near-death experiences, does he really understand the joy of being alive

Photo:independent.co.uk

'Up until my 24th birthday I had a straightforward and easy life. If asked, I probably would have said that I was enjoying life. However, a week after my 24th birthday, a chain of events began that rendered the gentle contentment that I had been accustomed to completely untenable. These events have made me appreciate how it actually feels to be genuinely excited to be alive.

On 20 February 2008 my partner, Emma, and I were house-sitting my grandparents' flat when the unserviced boiler gave way in an unrelenting spray of carbon monoxide. Apparently my only wish before passing out was to get naked and head to the loo one last time and, but for the resilience of Emma (in calling 999 before she passed out) and the bravery of the emergency services (in entering an unsafe building without proper breathing equipment), I would have died naked on the loo. Emma and I would have joined the 21 people in Britain who died of carbon monoxide poisoning in 2007/08. They reckon that another five minutes could have made the difference.

I'm told that while I was in hospital I was happiness personified but, to this day, I can't remember the events of that morning or much of what happened in hospital. I suffered from short-term memory loss for four weeks, which wreaked havoc with my confidence. This wasn't helped by a newfound awkwardness with social situations; I was reluctant to admit to myself what had happened to me so that conversation was off limits, but I found it almost as hard to talk about other issues...'- Continue to read

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 3747

Polluted legacy: Repairing Britain's damaged landscapes

"The Industrial Revolution, which made Britain the powerhouse of the world in the 19th Century, may have been consigned to the history books but it has left a legacy of environmental problems. Experts warn it continues to pollute drinking water, poison rivers and threaten flooding and in the process it fuels climate change and affects huge swathes of the modern landscape. The mining of lead, tin and other metals is thought to have contaminated nearly 2,000 miles of waterways. Estimated repair costs run into the hundreds of millions."...

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 7392

The Times in London has run a series of articles shedding light on the secretive tax avoidance industry, revealing how the rich and famous have resorted to complex schemes which have in some cases reduced the amount of tax paid to one or two percent. The evidence was gained by investigative reporters posing as potential tax avoiders seeking ways of reducing the tax they needed to pay. As the journalists have pointed out the schemes are perfectly legal, though questions have been raised as to whether they are moral.

The problem of tax avoidance in nothing new. The problem is that it is only the rich who can afford these schemes. Years ago a retired judge told me that, when he was a top earning QC, his accountant had said to him: ‘Now, Sir Kenneth, you are earning enough not to pay tax’.

Rather than pillorying individuals and giving the taxman more Draconian powers over our lives, undermining our civil liberties, why do we not acknowledge that our present tax system is unfair and not fit for purpose? To do that, of course, is to raise the question: What is the alternative?

Some twenty years ago Dr Ronald Burgess published a book entitled Public Revenue without Taxation. Impossible we might say – after all Benjamin Franklin pointed out that there are only two things certain in life: Death and Taxation. Burgess’s argument rests on recognising that we all benefit, not only from public expenditure on infrastructure and services, but also from each other’s activity and presence. This benefit is measured by market forces in what we are willing to pay to acquire a property, domestic or commercial.

To fully appreciate his argument, we need to recognise that the term ‘property’ conjoins two elements which are fundamentally different in nature: the bricks and mortar, and the land on which the building stands. The former is the product of human effort, the latter is the gift of nature – nobody made it. Anyone who owns a house or office block knows it is a depreciating asset which requires constant maintenance for its upkeep. When we talk of property prices rising we are referring to the land element. It is the value of the site which rises and falls with market conditions.

To test the veracity of this, we have only to move Selfridges from Oxford Street in London’s West End to mid Wales. There would be no underground or buses to deliver customers by their thousands to its doors, so the building would be largely valueless, at least as a shop. So what adds value to the Selfridge site are all the services and customers delivered by society to its doors. The value of the building is rightfully the property of Selfridges, but to whom does the location value rightfully belong?

If we, as a society, were to acknowledge that it is we, society collectively, and past generations, who have created the value of the site, would it not be reasonable for society to ask Selfridges to pay a ground rent for the privilege of occupying that site?

Were all of us to pay an annual market-determined ground rent for the site(s) of our choice to the government, acting as the agent of society, the need for our present complex and unfair system would reduce if not wither – but the point is that no one could avoid paying their due – you cannot hide the land or move it to another country. The rich own all the best properties and so would pay the most ground rent, regardless of whether they were domiciled for tax purposes in the country, and the rest of us according to our means. What could be fairer?

Because the rent cannot be avoided, the cost of collection would also be very low. The Times reports that there are currently ‘billions of pounds of potential revenue tied up in [a backlog of] more than 20,000 tax tribunal cases’ and almost one billion has been allocated to ‘tackle avoidance, evasion and fraud’. Contrast this with a report from The Economist in 1998 which describes the introduction of a tax on site values in Estonia. The collection rate in 1996 was said to be 95.5%.

But the benefits of raising public revenue from annual site values or ground rents go further than this. We have become so inured to paying taxes, believing there is no alternative way of funding the public services we all need, that little attention is paid to how damaging taxation is to enterprise. We are, in effect, trying to drive the economy with the handbrake on. As Lord Soames, Winston Churchill’s son-in-law, pointed out in the House of Lords: ‘If one were to set out with a specific, stated objective of designing a tax system which would penalise and deter thrift, energy and success, it would be almost impossible to do better than the one which we have in this country today.’ That was in 1978. It is worse now.

The Economist article described another important consequence of basing taxes on the site value: ‘The land tax, even at a modest 2% of the site value, encourages [owners] to develop the property or sell it. Government waste of land is penalised too: public sector owners must also pay the tax’. What a stimulus this would be to an economy mired in recession!

An important caveat is needed with regard to site values: the tax needs to be levied on the annual rental value of the site rather than its capital value. A further point to note is that no tax would be levied on the buildings on the site so there would be no disincentive to development. On the contrary, the incentive would be to maximise the potential of the site.

The argument put forward by Ronald Burgess in Public Revenue without Taxation was neatly encapsulated in the title of the Korean edition of his book: Let’s Abolish Taxes and Collect the Rent.

Anthony Werner, a graduate of the Universities of Cape Town and Oxford, has spent his working life in publishing, first at Oxford University Press and for the last 35 years at Shepheard-Walwyn Publishers in London. books@shepheard-walwyn.co.uk

ABOUT KAMRAN MOFID’s Blog and GUEST BLOG

KAMRAN MOFID’s Blog: Dedicated to the Common Good- aiming to be a source of hope and inspiration; enabling us all to move from despair to hope; darkness to light and competition to cooperation. “Whatever you can do or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it”. —Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

“When we are dreaming alone it is only a dream. When we are dreaming together it is the beginning of reality”. —Helder Camara

KAMRAN MOFID’s GUEST BLOG: Here on The Guest Blog you’ll find commentary, analysis, insight and at times provocation from some of the world’s influential and spiritual thought leaders as they weigh in on critical questions about the state of the world, the emerging societal issues, the dominant economic logic, globalisation, money, markets, sustainability, environment, media, the youth, the purpose of business and economic life, the crucial role of leadership, and the challenges facing economic, business and management education, and more.