- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 790

N.B. Many researchers and analysts have noted that, generalised trust, the belief that most other people can be trusted, is thought to positively influence individuals and society in a multitude of ways. High trust is associated with better physical and mental health, increased cooperation, well-being, and satisfaction with life.*

Trust in other people is so important because many aspects of fighting a pandemic – such as social distancing, wearing masks, washing hands, etc – require collective action in the interest of the greater good.-Photo:CORDIS-EU

‘Trust in other people is so important because many aspects of fighting a pandemic require collective action. The only way to break a chain of infection is if everyone takes part, for example by following the rules around social distancing. Individuals are much more likely to change their behaviour if they trust others to do so as well. After all, if you expect others to break the rules, why should you be the sucker still sitting at home?’

'We’ve found one factor that predicts which countries best survive Covid.'

By Thomas Hale Via The Guardian

'Trust between people – not in government or institutions – is key to limiting damage in a pandemic, our research shows.'

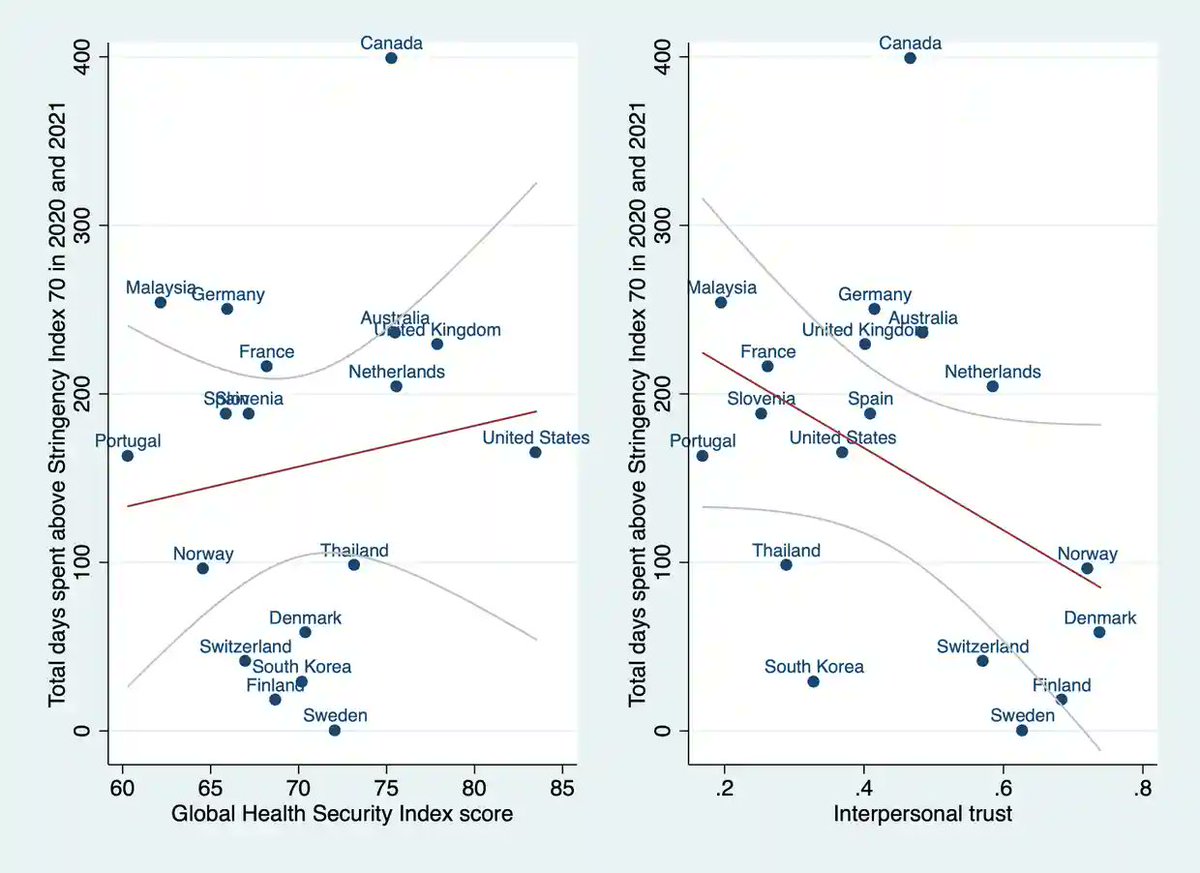

‘In 2019, the Global Health Security Index published a report ranking countries on their preparedness for pandemics. The US scored highest, followed by the UK. Two years later, both countries rank among those with the greatest loss of life from Covid. How could this be?

A large part of the answer is trust. Countries that looked good on paper in 2019, such as the US, UK, Spain and Slovenia, found they lacked this intangible but critical layer of defence. And this figure from our research over the past two years at the Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker shows it in stark terms. On the left (see below) you can see that a higher global health security score in 2019 is not correlated with fewer deaths during the pandemic, at least among the countries whose health systems have a minimum threshold of capacity.

Photo: Blavatnik School of Government/University of Oxford/The Guardian

But on the right, we see that a far better predictor of how many people would die – or survive – during the pandemic is the level of interpersonal trust in a society. This doesn’t mean trust in governments or institutions: both have received lots of coverage during the past two years, and yet appear to have little effect. Rather it’s a measure of how much people think they can trust another citizen who they don’t already know.

At every stage in this pandemic, this kind of trust has been a vital resource. After two years we can now see clearly how important it was, raising the question of how we might build it up to deal with both the ongoing threat posed by Covid, and the next pandemic.

Results from the past two years show that the extraordinary measures we were asked to follow to “flatten the curve” really can work to reduce or even eliminate infections, particularly when they are deployed during the beginning of a wave. But dig in a little further, and we see that these restrictions work better – and often don’t have to be as harsh or long – in high-trust countries…’-continue to read

* read more on generalised trust HERE

In All We Do, Trust is of the Essence

Trust is so Vital to Who we are and How we Live our Lives

A pick from our archive

Photo:shutterstock.com

Why Love, Trust, Respect and Gratitude Trumps Economics

Crisis in Trust and Perpetual Global Crisis

In Praise of Magna Carta: What happened to Trust and Democracy in Britain?

Kindness to Heal the World- Kindness to Make the World Great Again

Build a Better World: The Healing Power of Doing Good

How to Restore Trust in VW again?

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 683

Photo: Via The Guardian

‘Money corrupts the process of reasoning.’- Roy L. Furman, Professor of Law and Leadership, Harvard Law School

Paraphrasing the wise words of Lord Acton about power, I can say: Money Corrupts and Loads of Money Corrupts Absolutely

“In London, money rules everyone. Anyone and anything can be bought.”- A Russian Oligarch on why he loves London!

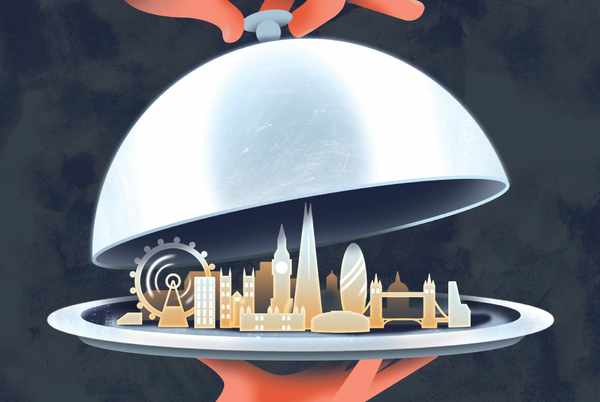

How the British upper class came to serve the global elite*

By Andy Beckett Via The Guardian

‘From banking to boarding schools, the British establishment has long been at their service, discretion guaranteed.’

‘Other secretive countries, such as Switzerland, have been doing it for longer. Yet Britain has offered oligarchs an unusually broad range of opportunities, from the chance to own famous football clubs to money laundering through prestige property; from private education for their children to a ruling party that isn’t squeamish about who funds it.’

Illustration by Thomas Pullin/ The Guardian

‘Who better to understand the needs of global capitalism’s mega-rich than Britons who grew up with staff themselves?’

‘Britain is good at wealth. Not necessarily at generating it, or distributing it in ways that make a contented society, but at looking after it, helping it grow and making it respectable – converting it into social and cultural capital. For centuries, British bankers, lawyers, accountants and other assistants to the wealthy have discreetly performed these roles.

Their customers used to be mostly British: slave traders, self-made industrialists, people who had extracted fortunes from our colonies. But in recent decades, foreigners have become the main beneficiaries of Britain’s readiness to serve the rich regardless of how they made their money. So significant is this change that Britain has become “butler to the world”, according to a persuasive new book by the anti-corruption campaigner and journalist Oliver Bullough.

Other secretive countries, such as Switzerland, have been doing it for longer. Yet Britain has offered oligarchs an unusually broad range of opportunities, from the chance to own famous football clubs to money laundering through prestige property; from private educations for their children to a ruling party that isn’t squeamish about who funds it.

The economic crime bill, finally going through parliament after years of delays, may reduce this activity: by requiring that foreign owners of land and property be more clearly identified, and by making investigations easier into those with “unexplained wealth”. Sanctions against some Russian oligarchs after the invasion of Ukraine are bringing parts of Londongrad to an abrupt halt. But Bullough says these belated measures don’t go nearly far enough. Meanwhile the capital and the plushest home counties suburbs will go on servicing plutocrats from elsewhere.

For a country that was a superpower less than a lifetime ago, being a butler to the elites of other countries that have overtaken it seems quite a drop in status. In 2007, the social commentators Peter York and Olivia Stewart-Liberty described the increasing number of companies set up by posh English people to ease the lives of the super-rich – such as Quintessentially, co-founded by Ben Elliot, nephew of the Duchess of Cornwall and now Conservative party co-chairman – as a “master-turned-servant” phenomenon. The same could be said of older British institutions such as the City of London, which used to finance the British empire but now largely works for its successors.

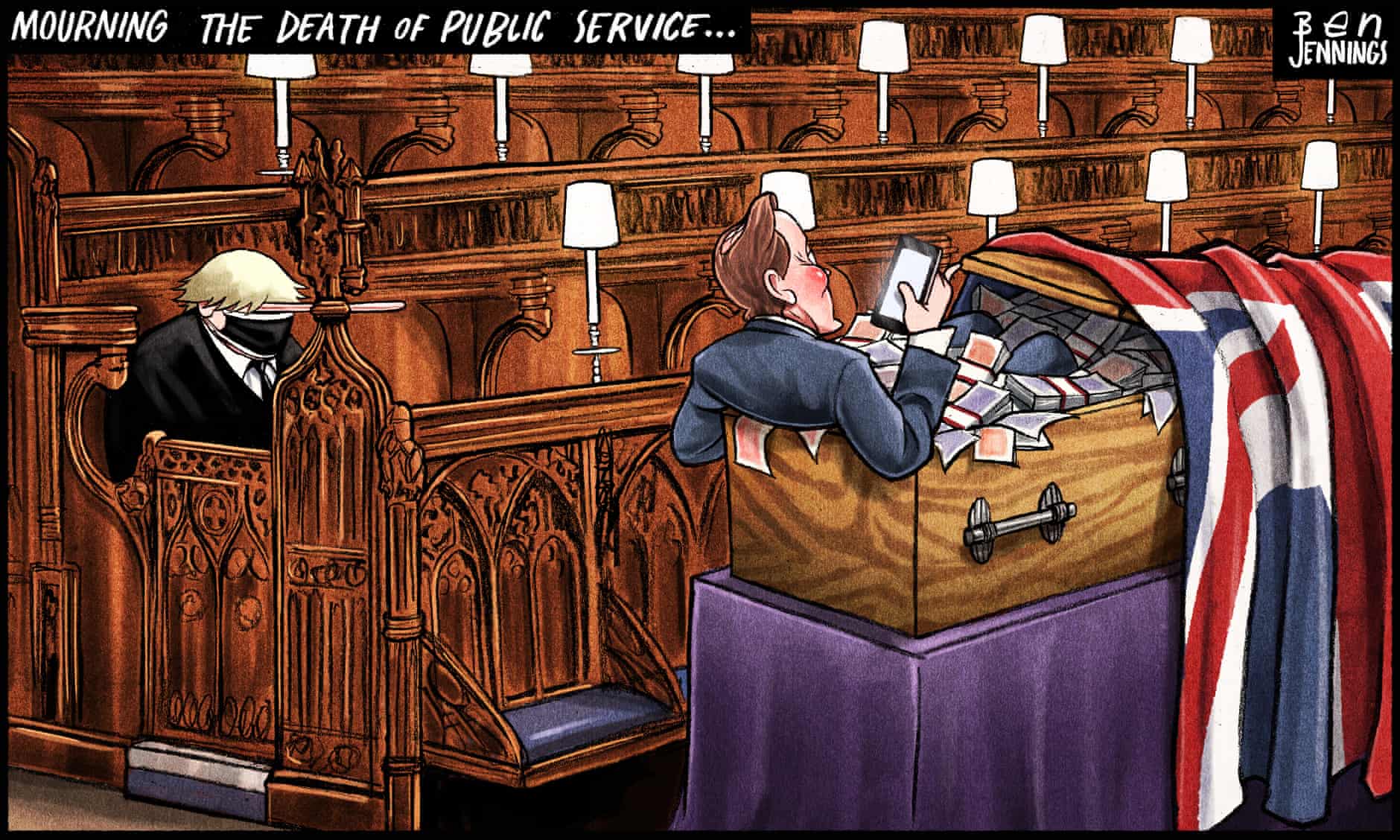

Britain Has Become a Sinking Ship of Systemic Corruption, Cronyism and Chumocracy

How have our elites managed to adjust to and rationalise this switch in roles? One obvious answer is that working for foreign tycoons can be very profitable. A more counterintuitive explanation is that running an empire and organising things for rich clients require some of the same qualities: confidence, good contacts and a belief in hierarchy as the natural state of the world. As global capitalism has created ever more privileged winners, who better to understand their needs than Britons who grew up with staff themselves?

You could also see in this aristocratic entrepreneurialism a final victory for Thatcherism. Long after the British working class and middle class, at least some of the upper class have got used to selling themselves. They don’t “have the old inhibitions about being pushy”, York and Stewart-Liberty wrote. With the new foreign money making life in London more expensive, the upper classes “can’t afford that old false modesty”.

Serving the international super-rich can also be a way of escaping Britain. In 1973, the historian Jan Morris identified among British imperialists “a recurrent yearning to break out” of these islands “into more vivid places, where fortunes can be made, outrageous enterprises undertaken, and the restrictive rules … disregarded”. In a smaller but similar way, working for an oligarch can make you feel part of a global adventure, close to real power – while leaving Britain’s problems for others to try and solve.

It was in the 1970s, the first decade after the empire’s final dismantling, that London began welcoming Middle Eastern tycoons who wanted to spend, invest and hide their oil money. A new breed of British estate agent, specialising in ultra-expensive property, emerged to cater to them. The growth and polarisation of the Russian, Chinese and Indian economies from the 90s onwards produced further waves of newly wealthy people, looking for business and pleasure in high-status western cities. London successfully sold itself to them as a place of good taste and tradition – and lower taxes than New York or Paris.

Sometimes, this process was seen as part of “the Wimbledon effect”: the idea, named after the tennis tournament, that what matters to the British economy is not the nationality of the competitors, but where the competition happens.

Could post-imperial Britain have chosen to provide different, less morally compromised services to the outside world? Arguably for much of the postwar period it did. From the 60s to the 90s, what Britain primarily sold to foreign visitors was the mass culture made possible by social democracy: innovations in pop music, street fashion and television, subsidised by more generous unemployment benefits, a more confident BBC and free university education.

That vibrant pop culture still exists, but it feels less central to British life and less globally influential. Today, London in particular is known to the world’s wealthy as a place to eat in expensive restaurants, park your supercar outside Harrods and check on your barely used properties and hidden investments. It’s an economic model that works, up to a point, except when geopolitical shocks disturb it. But for those who can’t afford or don’t provide its services, it offers little. If all the oligarchs ever leave, we won’t be mourning.’-*This article by Andy Beckett was first published in the Guardian on 10 March 2022

For all those in Search of Truth: A Must-read Book

Butler to the World

The book the oligarchs don't want you to read - how Britain became the servant of tycoons, tax dodgers, kleptocrats and criminals

Bestselling author Oliver Bullough reveals the scandalous reality of Britain's new position in the world.

‘'A savage analysis of Britain's soul. As essential as Orwell at his best' Peter Pomerantsev 'Horribly brilliant' James O'Brien The Suez Crisis of 1956 was Britain's twentieth-century nadir, the moment when the once superpower was bullied into retreat. In the immortal words of former US Secretary of State Dean Acheson, 'Britain has lost an empire and not yet found a role.' But the funny thing was, Britain had already found a role. It even had the costume. The leaders of the world just hadn't noticed it yet. Butler to the World reveals how the UK took up its position at the elbow of the worst people on Earth: the oligarchs, kleptocrats and gangsters. We pride ourselves on values of fair play and the rule of law, but few countries do more to frustrate global anti-corruption efforts. We are now a nation of Jeeveses, snobbish enablers for rich halfwits of considerably less charm than Bertie Wooster. It doesn't have to be that way.’- Purchase the book HERE

Read more:

How Putin’s Oligarchs Bought London

Gas-powered kingmaker: how the UK welcomed Putin’s man in Ukraine

Inside the £250m Abramovich property portfolio

We claim Britain is an ethical democracy - but oligarchs know that’s not true

Western values? They enthroned the monster who is shelling Ukrainians today

- Details

- Written by: Kamran Mofid

- Hits: 1162

Beatrix Potter's stories have captured the imagination of readers across the generations

Photo:wonderguide

The Secret Life of Beatrix Potter

A new book and an exhibition on Potter, who wrote “The Tale of Peter Rabbit,” use letters, sketches, and a coded journal to capture an author who delighted in the detail and humour of the natural world.

BY Anna Russell Via The New Yorker

‘Many teen-agers will go to great lengths to keep their diaries private—I kept a little key for mine in a wooden jewellery box, which I guarded jealously—but the children’s book author Beatrix Potter took it to an extreme. Between the ages of fourteen and thirty, she fastidiously recorded observations about her stiff Victorian world in several journals. Her parents, descendants of wealthy cotton merchants in the North of England, were rich and exceedingly proper. Perhaps to protect her work, Potter wrote in a minuscule handwriting using a code that only she could understand. Her journals remained a mystery until 1958, when a collector, searching through them, identified a passing reference to Louis XVI, and then painstakingly decoded years’ worth of Potter’s innermost thoughts.

In public, Potter, the author of “The Tale of Peter Rabbit” and “The Tale of Benjamin Bunny,” whose books have now sold more than two hundred and fifty million copies, was demure and perfectly respectable. In private, the journals suggest, she was forthright and opinionated, a budding artist, who delighted in the detail and humour of everyday life. “She was quite a strong and determined personality,” Annemarie Bilclough, who co-curated an exhibition on her life at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, told me. Born in 1866, Potter lived with her parents in a grand house in South Kensington, a rapidly growing community, until she was forty-seven years old. She felt like an outsider much of the time. She hated the noise and grime of the city—“Why do people live in London so much?” she wondered—and longed to be in nature. She called her birthplace “unloved.” “My brother and I were born in London because my father was a lawyer there,” she wrote. “But our descent—our interests and our joy was in the north country.”

What was Potter doing all that time she lived at home with her parents? In childhood, she rarely ventured into the rest of London, and she had few friends besides her younger brother, Bertram. Mostly, it seems, she spent her days drawing. She drew compulsively, rapturously, from a young age, in a sketchbook that she made from drawer-lining paper and stationery. “It is all the same, drawing, painting, modelling, the irresistible desire to copy any beautiful object which strikes the eye,” she wrote. She drew when she was unsettled, regardless of the subject. “I cannot rest, I must draw, however poor the result, and when I have a bad time come over me it is a stronger desire than ever, and settles on the queerest things,” she wrote in her journal. “Last time, in the middle of September, I caught myself in the backyard making a careful and admiring copy of the swill bucket, and the laugh it gave me brought me round.”

Potter’s sketchbook and coded journal, and many of her other belongings, are on display at the V. & A. through early next year, in an exhibition titled “Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature.” (Rizzoli has recently published an accompanying book by the same name.) Some two hundred and forty eclectic objects, including manuscripts, sketches, tchotchkes and collectibles—even the alleged pelt of Benjamin Bunny–—tell the story of a remarkable transformation. Having lived the first two-thirds of her life in near-total acquiescence to her family’s wishes, she made a sudden turn in her third act. “A town mouse longing to be a country mouse,” as Bilclough put it, Potter gave up the trappings of her privileged life in London and bought a cottage in a remote part of the English countryside. She became a farmer and conservationist, with muddy shoes and prize-winning sheep. She walked the fells and lakeside paths around her new home, sketching them, and ultimately saving them from destruction.

Potter may not have had many friends as a child, but she had lots of animals. She and Bertram sneaked a rotating cast of pets into their nursery, including snakes, salamanders, lizards, rabbits, frogs, and a fat hedgehog. The V. & A. exhibition, which includes a series of dark rooms that evoke the cloistered atmosphere of Potter’s childhood, showcases her early drawings of the natural world as she would have known it then: a mouse, a caterpillar, a beady lizard. The siblings loved animals, but they were “unsentimental about the realities of life and death,” as the show puts it. When their pets died, they would stuff them, or boil their skeletons for further study. There’s a drawing by Bertram of a pickled fish next to a human skull, and a note from him about his pet bat: “If he cannot be kept alive . . . you had better kill him, + stuff him as well as you can,” he wrote to Potter from boarding school. Nearby, stretched out in a display case, is a flattened rabbit hide and the disturbing sign, “Rabbit pelt, thought to be that of Benjamin Bouncer.” Benjamin Bouncer was one of a series of rabbits that Potter owned, and a favourite muse. She brought him home in a paper bag when she was in her teens. Later, she brought home the rabbit Peter Piper, who learned how to jump through hoops but “flatly refused to perform” in company.

In early adulthood, Potter observed her pets closely, inventing narratives about them, and filling her letters to the children of friends with their adventures. Her dispatches are playful and alive, illustrated with pen-and-ink drawings of rabbits. In 1892, she wrote a letter to Noel Moore, the son of her former governess, about an encounter that Benjamin Bunny had with a wild rabbit in the garden. (Benjamin hardly noticed; he was eating so much.) After Benjamin died (“through persistent devotion to peppermints”), Peter Piper became Potter’s leading man. In 1893, she wrote to Noel again: “My dear Noel, I don’t know what to write to you, so I shall tell you a story about four little rabbits whose names were Flopsy, Mopsy, Cottontail and Peter.” A drawing of a whiskered Peter on his hind legs, ears perked, immediately suggests mischief.

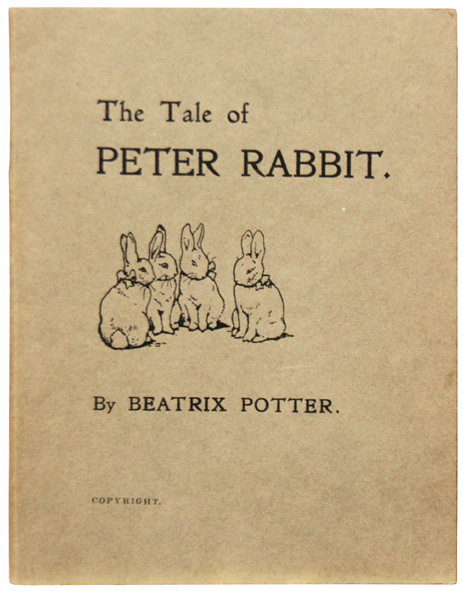

Potter sent the Moore children story after story in illustrated letters, until Noel’s mother suggested that she try to turn them into books. (The children had saved their copies.) In 1901, Potter self-published the first edition of “The Tale of Peter Rabbit,” which appeared almost exactly as she had written it to Noel, down to Peter’s “blue jacket with brass buttons, quite new.” A series of established publishers had turned her down, partly because of her insistence on keeping the book’s price low. “Little rabbits cannot afford to spend 6 shillings on one book, and would never buy it,” she wrote to a friend. She was also particular about the size of the book; it had to be small, for small hands. The following year, Frederick Warne & Co. agreed to put out an abridged version. Potter compromised on the cover image, which she called the “idiotic prancing rabbit.”

Peter Rabbit first edition, first printing. December 1901. Photo:Peter Harrington, London

“Peter Rabbit” was an instant hit, selling out multiple editions. (“The public must be fond of rabbits! what an appalling quantity of Peter,” Potter wrote.) Her publisher asked for more books, and she began pumping them out one after another, beginning with “The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin” and “The Tailor of Gloucester.” She also patented her characters. In the exhibition, there’s a fraying Jemima Puddle-Duck doll, with a fabric bonnet and shawl, and a Peter Rabbit teapot, as well as a complicated-looking board game. “She was very savvy in what was created, and what was made,” Helen Antrobus, who co-curated the show, told me. Potter believed that her first books found an audience because they were written for real children. “It is much more satisfactory to address a real live child,” she wrote. “I often think that that was the secret of the success of Peter Rabbit, it was written to a child—not made to order.”

She also had a knack for making the familiar strange. Her attention to the practicalities of being an animal, even a very civilised one, produced beguiling images. If a hedgehog wears a bonnet, as one does in “The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle,” her quills will certainly poke through. If a tortoise is invited to a dinner party, as happens in “The Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher,” he’ll probably bring a salad in a string bag. She took silliness seriously. At the V. & A., one display case holds tiny folded letters that Potter wrote as if they were sent from one character to another: “Letters between Squirrel Nutkin, Twinkleberry Squirrel and Rt Hon. O. Brown, Esq. MP.”...Continue to read

Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature – February 22, 2022 By by Annemarie Bilclough

‘This beautiful book explores the beloved writer’s achievements

as a storyteller, artist, and naturalist.

Beatrix Potter’s universe of characters—Peter Rabbit, Squirrel Nutkin, Jemima Puddleduck—have delighted audiences for over a century. A creative pioneer and determined entrepreneur, she combined scientific observation with imaginative storytelling to create some of the world’s best-loved children’s books. This volume showcases Potter’s charming charac-ters against the backdrop of her exquisite botanical drawings, humorous illustrated letters to friends, Lake District landscapes, and rarely seen photographs.

Beatrix Potter’s endearingly hand-painted world of animals and gardens made her one of the most celebrated children’s book authors of all time, yet this is but one facet of her creative life. Drawn to the picturesque English countryside after a London childhood, Potter had a passion for nature that influenced her many achievements as a naturalist, artist, storyteller, and later in life as a fervent conservationist and “gentlewoman” farmer. This book sheds light upon the connections between her art, entrepreneurial success, and legacy in preservation.’- Buy the book HERE

Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature

Celebrating the life and work of one of the best loved children's authors of the 20th century

Discover the life and work of Beatrix Potter in an immersive exhibition that explores her enduring love of nature.

Photo: Via HR Grapevine

‘The V&A is home to the world’s largest collection of Beatrix Potter-related materials in the world. Bequeathed to the museum by engineer and enthusiast Leslie Linder, the man who decoded Potter’s secret diary, the collection spans drawings, manuscripts, correspondence and photographs.

Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature uses this extensive archive to explore the lasting legacy of one of the best-loved children’s authors of the 20th century. Her love for the natural world is evident from the letters, sketches and paintings on display – a passion that began with drawings documenting the distinguishing characteristics of animals when Potter was only eight years old.

Realised through a major partnership with the National Trust, the exhibition highlights Potter's work as a farmer and conservationist in the Lake District, which helped to inform the careful accuracy of her illustrations, whilst building on the success of the V&A’s family-friendly shows with playful staging and immersive design.’- Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature at V&A

Beatrix Potter: the lady of the Lakes

Beatrix Potter devoted her life to protecting the Lake District, and it has thanked her with some elegant literary memorials

'One of the most visited places in England's Lake District National Park is Hill Top Farm. It was owned by Beatrix Potter,

the creator of Peter Rabbit and nearly two dozen other children's classics'.-Photo:YouTube

‘‘Though she will forever be associated with the Lakes, Potter was born in London in 1866, and fell in love with Cumbria while on family holidays, which continued into her 30s. It was on one of these later visits that she began to dream up her stories of anthropomorphic woodland animals, initially presented in letters to young children of her acquaintance.’- Read the article HERE--- Learn more and visit the Hill Top HERE

Beatrix Potter, the Lake District and the National Trust

Yewtree Farm/Coniston-Cumbria Painting by David Sims

Yew Tree Farm, near Coniston in the Lake District, was one of a number of properties owned by Beatrix Potter. The property is now owned by the National Trust.- Learn more about Beatrix Potter’s love for the Lake District and her legacies to the National Trust HERE

‘The World of Beatrix Potter™ is a vibrant family Attraction bringing to life Beatrix Potter’s enchanting stories in a magical recreation of the beautiful Lake District countryside. The exhibition features favourite characters from the famous books, an award-winning outdoor Peter Rabbit Garden, a superb character-themed family-friendly café and world-famous gift shop ensuring all generations of visitors can experience a little bit of Beatrix Potter magic.’

Photo: TheWorldofBeatrixPotter

The World of Beatrix Potter Attraction, The Old Laundry, Crag Brow, Bowness-on-Windermere, Windermere, Cumbria, LA23 3BX HERE

Our GCGI Love Letters To Our Mother Nature and Earth

Healing the world as if the web of life mattered

A Pick from our Archive

The Wisdom of Mother Nature belongs to all Life.

'Be like the sun for grace and mercy.

Be like the night to cover others’ faults.

Be like running water for generosity.

Be like death for rage and anger.

Be like the Earth for modesty.

Appear as you are.

Be as you appear.'- Rumi

Coniston Water- Getty Images

Environmental Crisis, Hope and Resilience: A Pick from our GCGI Down to Earth Archive

Detaching Nature from Economics is ‘Burning the Library of Life’

Desperately seeking Sophia: The Wisdom of Nature

On the 250th Birthday of William Wordsworth Let Nature be our Wisest Teacher

Celebrating the joyous Spring with Hopkins and Wordsworth

The beauty of living simply: the forgotten wisdom of William Morris

‘Open our minds and touch our hearts, so we may be attentive to Your gift of creation’

Spirituality and Environmentalism: Healing Ourselves and our Troubled World

I went to the woods to live deliberately- Henry David Thoreau

In this troubled world let the beauty of nature and simple life be our greatest teachers

Land As Our Teacher: Rhythms of Nature Ushering in a Better World

Are you physically and emotionally drained? I know of a good solution!

Ten Love Letters to the Earth: “Walk as if you are kissing the earth with your feet”

The prophetic legacy of John Ruskin: A Man ahead of his time

What a blissful day it was visiting "The loveliest spot that man hath ever found

GCGI is our journey of hope and the sweet fruit of a labour of love. It is free to access, and it is ad-free too. We spend hundreds of hours, volunteering our labour and time, spreading the word about what is good and what matters most. If you think that's a worthy mission, as we do—one with powerful leverage to make the world a better place—then, please consider offering your moral and spiritual support by joining our circle of friends, spreading the word about the GCGI and forwarding the website to all those who may be interested.

- War and Peace: A Timeless Lesson from Coventry

- Today, as the world seems so bleak, can we hack our happy hormones for a blast of positivity?

- I pray to our Mother Earth, I pray to the Birds and I pray for a New Day, the Happy Norouz

- War is the Failure of Humanity: The Tragedy of What We Are Collectively Doing

- World in Chaos and Despair: The Healing Power of Meister Eckhart’s Four Es