Remembrance Sunday 2016

Beyond the Agony and Hatred

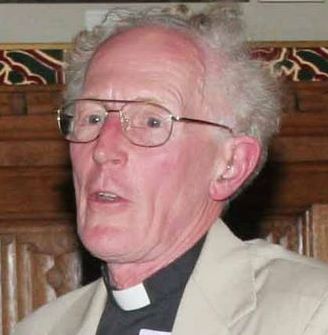

A Story of Suffering and Hope by Rev. Marcus Braybrooke*

Rev. Marcus Braybrooke

On Remembrance Sunday, it is right first to express our sympathy to those wounded in or bereaved by War. We think especially of the victims of Two World Wars, but sadly we also remember more recent conflicts and their many victims. We also give thanks for those who sacrificed or risked their lives for others and for those who labour for reconciliation.

May our remembering bring them some comfort and strength.

Today is not the time to discuss the rights and wrongs of past conflicts, but to pray that past sacrifices may both makes us grateful for the freedom we enjoy and renew our commitment to work for a more just and peaceful world.

I am so used to thinking of the Cross as a sign of God’s love that it came as something of a shock when someone said it is a sign of human evil. This, of course, is true. The cross is a symbol of human cruelty just as much as it is a symbol of new life.

It was at the church of St Peter in Gallicantu in Jerusalem that I felt most vividly the cruelty and torture that Our Lord endured. It is thought that this church is built on the site of the High Priest’s house, where Jesus was taken after he had been arrested. You go right down into a pit, probably once a cistern. It is there that a prisoner was thrown (as also happened to the prophet Jeremiah). There was no way out. The pillars still have marks of the metal rings to which prisoners were chained when they were stretched out to be flogged. In the pit below you could their cries, as you, as a prisoner, would have waited your turn.

Different methods of torture are used today – but there are different pits and prison cells where the cruelty and agony are the same. We can be thankful if we have been spared such agony, but unless, at least in our imagination, we have tried to come alongside the victims, our preaching of the Cross as a symbol of love may seem superficial.

When I was Director of the Council of Christians and Jews hardly a day passed without some vivid reminder of the horrors of the Holocaust. I still remember someone telling me that two hundred of his relations were murdered in the concentration camps – to which there is no answer. I have tried to take seriously the words of the German theologian Johann-Baptist Metz that ‘there is no God to whom I could pray with my back turned toward Auschwitz.’ If our words are to be authentic then they have to be spoken in the presence of burning children, whether in Auschwitz or Aleppo.

Yet, it was in Auschwitz that Rabbi Hugo Gryn, who was well known as a contributor to the BBC’s Moral Maze, found faith. I was on the Day of Atonement. Hugo, fasting, found somewhere to hide and recited to himself many of the prayers. ‘I sobbed for hours,’ he said, ‘I have never cried with such intensity and then I seemed to be granted curious inner peace… I was found by God… I believe that God was there himself – violated and blasphemed.’

I had something of the same feeling when I visited Hiroshima. On the way there, I did not know if I could face the experience. I was shown round by a survivor. She was six at the time when, from a clear blue sky, the deadly bomb dropped. She told me of the horror of that day – going home to find there was no home, looking for her parents to find she had now no parents – and then the physical effects of the radiation and the endless operations and as she somewhat recovered being shunned by many younger Japanese people, who wanted no reminder of their past. She was a Buddhist – there was no sense of bitterness or self-pity. She showed me round the Peace Park and at the end by one of the memorials we were silent. She was ashamed of Japanese treatment of prisoners of war, I was aware of British responsibility for the suffering of the people of Hiroshima – but in the silence I was aware of an overwhelming sense of the ‘peace that passeth all understanding’ – that beyond the wraths and sorrows of the world there is another reality of a Love which holds all the world in its embrace.

Christianity is not escapism. It is almost too realistic to bear. We turn away from suffering in Aleppo and so many other places. The press admits there are pictures which are too gruesome to print. It is no wonder that so many who had endured the trenches or other wars did not wish to speak of it when they came home. The Cross confronts us with the reality of evil.

As we contemplate the Passion of Our Lord we see him taking upon himself the pain of all who suffer. As Timothy Rees, who served in the trenches, wrote

Today we see your passion

Spread open to our gaze

The crowded street, the country road

Its Calvary displays…

The groaning of Creation

Wrung out by pain and care

The anguish of a million hearts,

That break in dumb despair;

O crucified Redeemer,

These are your cries of pain

O may they break our selfish hearts

And love come in to reign.

But we also look inwards and we recall our own selfishness and lack of love –our own potential to deceive and act with cruelty. In other circumstances would we have behaved better? Yet in the midst of the horror there is the heroism. Think of the courage of a soldier under enemy fire risking his life to carry back a wounded comrade; of a fireman entering a burning building; of a mother jumping into a river to save a drowning toddler. Pray too for those doctors and nurses in Aleppo who still try to bring comfort to those whose limbs have been shattered by bombs.

All of us, the Bible says, are made in the divine image. We are called to grow up into the likeness of Christ, but we cannot do this of ourselves – it is only when we recognise our own potential for evil, our own failures and throw ourselves at the foot of the Cross and allow God to transform us. It is there that we know there is power stronger than death, a love, which no evil can obscure.

But the future is open. God does not compel, but asks us to choose between good and evil. Will we share with God in the redeeming of the world? Will we open ourselves so God’s love can flow through us into the war-torn waste places of the Earth?

As we remember to day those who died in war or in other ways gave their lives for others, we honour them and see in them witnesses to the Truth that amidst the darkness of the world a light shines – that God’s love is more powerful that human brutality. The Cross is a reminder of human evil, but far more it is a sign of Hope, a pledge of God’s unfailing Love. From the cross Jesus calls to us ‘Follow me: Share with me in “preaching good news to the poor, freedom for prisoners, recovery of sight for the blind, release for the oppressed and God’s goodwill to all people.”

Rev. Marcus Braybrooke, a GCGI Senior Ambassador, is a retired Anglican parish priest. He has been involved in interfaith work for nearly fifty years. He joined the World Congress of Faiths in 1964 and is now president. He served as executive director of the Council of Christians and Jews from 1984 to 1988, is a co-founder of the Three Faiths Forum and patron of the International Interfaith Centre at Oxford. He has travelled widely to attend interfaith conferences and to lecture. Rev. Braybrooke is author of over forty books on world religions, including Pilgrimage of Hope: One Hundred Years of Global Interfaith Dialogue (1992), the history of the interfaith movement’s first century, and Promoting the Common Good (with Kamran Mofid).