A reflection by Kamran Mofid PhD (Econ, Birmingham, 1986) & Certificate in Education in Pastoral Studies, Plater College, Oxford, 2001

And somehow the journey continues...

St. Peter's-On-the-Wall, Bradwell-On-The-Sea, Essex. It dates from between 660–662 and is believed to be the oldest active church in England.-Photo:wikimedia.org

Study after study have reported that, around the world, people, and especially the youth, have turned their backs on religion.*

Being without Believing: Is this the fate of the world In today's "post-modern society"?

If so, then, this saddens me. From the beginning , religion has been part of the human make-up, forming and shaping us. It has also been part of our cultural, spiritual, and intellectual discourse and history. Religion has been at the heart and foundation of literature, poetry, texts, stories, arts and architecture, our earliest attempt at cosmology, cosmos and psychology, philosophy, ethics and economics, the bridge between Nature and the human soul, making sense of where we are in the universe, and much more.

I, thus, hope that, one day, again, religions can become a source of human spirit of love and generosity, inspiring and empowering people to find answers to the timeless question of what it means to be human?

‘My religion is, to live through Love...In every religion there is love, yet love has no religion.’-Rumi

‘The World is my country, all mankind are my brethren, and to do good is my religion’-Thomas Paine

UK secularism on rise as more than half say they have no religion, according to the British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey for 2018

“The steady decline in religious belief among the British public is one of the most important trends in postwar history.”

“In just a decade the number proclaiming no faith has risen from 43% to 52%, as “secularisation continues unabated”. Back in 1983, the BSA’s first survey, two-thirds of the British called themselves religious. Now declining faith means that 12% are Anglicans, 7% Catholics, 19% another type of Christian, and 9% are of a non-Christian religion including 6% Muslims. Here’s the size of the shift towards outright atheism: a quarter of the public now boldly state “I do not believe in God”, compared with just 10% 20 years ago.”

What is Religion?

To Believe or Not to Believe that is the question

Photo:i.huffpost.com

‘UK secularism on rise as more than half say they have no religion’

This was the heading of an article in today’s Guardian(11 July 2019). In a recent survey, it is reported that only 1% of young people identify as Church of England and atheism is growing.

The gist of the report is noted below:

‘The growth of secularism in the UK is unabated with fresh data showing stark generational differences and a new confidence among the non-religious to declare themselves atheist.

Only 1% of people aged 18-24 identify as Church of England, according to the British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey for 2018. Even among over-75s, the most religious age group, only one in three people describe themselves as C of E.

Across all age groups, the younger people are the less likely they are to call themselves Anglican.

The steady decline in religious belief among the British public is “one of the most important trends in postwar history”, says the BSA report.

Fifty-two percent of the public say they do not belong to any religion, compared with 31% in 1983 when the BSA survey began tracking religious belief. The number of people identifying as Christian has fallen from 66% to 38% over the same period.

“Britain is becoming more secular not because adults are losing their religion but because older people with an attachment to the C of E and other Christian denominations are gradually being replaced in the population by younger unaffiliated people,” says the report.

“To put it another way, religious decline in Britain is generational; people tend to be less religious than their parents, and on average their children are even less religious than they are.”

Non-religious parents successfully transmit their lack of faith to their children, but two religious parents have only a 50/50 chance of passing on their faith, the report says.

The non-religious are increasingly atheist. One in four members of the public stated: “I do not believe in God,” compared with one in 10 in 1998. The figures challenge theories that people are “believing but not belonging” – in other words, that faith has become private rather than institutional – the report says.

The proportion of people who say they are “very or extremely non-religious” has more than doubled, from 14% to 33% in the past two decades.

Nevertheless, most people are tolerant of others’ religious beliefs. A large majority of both non-believers and people of faith have positive or neutral views of individuals who belong to a religion.

Only 3% of people say they would definitely not accept a mixed-faith marriage within their family, with 82% saying they would definitely or probably accept someone from a different religion marrying a relative.

As religious adherence declines, trust in scientific institutions is increasing, says the report. University scientists have a higher trust rating (82%) than corporate scientists (67%).

In terms of confidence in institutions, 11% of people say they trust churches and religious organisations, compared with 36% who have confidence in the education system, 34% in the legal system, 16% in business and industry and 8% in parliament.’

A pertinent question at this point must surely be: Why such a decline? Why only 11% of people have trust in religious institutions, the second lowest percentage after the parliament (8%)?

There must be many reasons for this. I don’t feel I am qualified enough to provide answers of all sorts to all of them. But, I feel confident enough, given my own life experience, journey and profession, to suggest, with utmost humility, the following:

Perhaps, it is time for our religious leaders, institutions and more, to engage people, and especially the youth, in a more spiritual, kinder way. More as a source of inspiration, beauty and wisdom, more dialogical, more talking with, rather than talking at. In short, more as a source of inspiration and less of dogmatic religiosity. In the words of Albert Einstein:

‘The religion of the future will be a cosmic religion. It will have to transcend a personal god and avoid dogma and theology. Encompassing both the natural and the spiritual, it will have to be based on a sense of intelligence arising from the spirit of all things, natural and spiritual, considered as a meaningful unity.’

Moreover, religion should be and be seen as being more concerned with the youth’s struggles, fears and anxiety about what they are going through, giving them hope, brightening their paths, becoming one with them, as they imagine a better life, a better world.

Religions and religious leaders should show more genuine and heartfelt sympathy and empathy with people’s pain of loneliness, hopelessness, virtual realities, economic and sociopolitical injustice, environmental and ecological degradation, insecurity, sexual orientation and gender identity, problems and challenges of personal and intergenerational relationships, and more.

‘Love is simply creation's greatest joy.’- Hafez

‘The lovers of God have no religion but God alone.’-Rumi

‘When I admire the wonders of a sunset or the beauty of the moon, my soul expands in the worship of the creator.’- Mahatma Gandhi

In this, a more spiritual path and two-way dialogue, youth can come to see religion and presence of God in the absolute wonder of life and the interconnection of all life as well as their own place in the entire web of life. Moreover, this kind of thinking, attitude and experience leads to the desire for action, understanding, debate, compassion, love, respect for all forms and aspects of life, ideas and insights.

In short, religion must encourage us to seriously and deeply think, ponder and reflect together on Life’s Big Questions, questions of meaning, values and purpose:

- What does it mean to be human?

- What does it mean to live a life of meaning and purpose?

- What does it mean to understand and appreciate the natural world?

- What does it mean to forge a more just society for the common good?

5- In what ways are we living our highest values?

6- How are we working to embody the changes we wish to see in the world?

7- What projects, models or initiatives give us the greatest sense of hope?

8- How can we do well in life by doing good?

By their very nature, these questions involve thought and discussion around spirituality, ethics, morals and values. This means that our lives are connected not only to knowledge, power and money, but also to faith, love and wisdom.

‘I have learned so much from God that I can no longer call myself a Christian, a Hindu, a Muslim, a Buddhist, a Jew. The Truth has shared so much of Itself with me that I can no longer call myself a man, a woman, an angel, or even a pure Soul. Love has befriended me so completely it has turned to ash and freed me of every concept and image my mind has ever known.’- Hafez

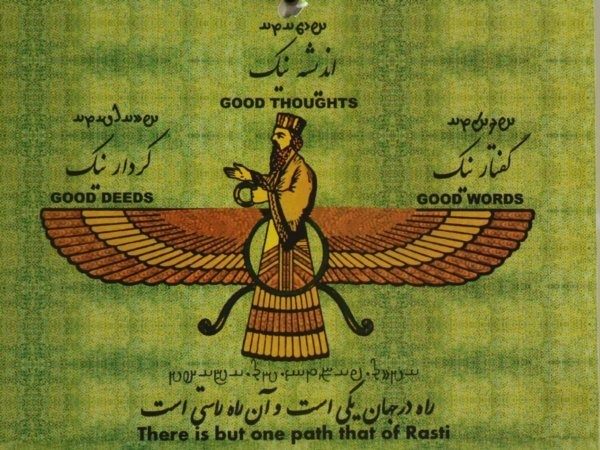

Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds

Think Good, Speak Good, Do Good

Doing Good is a simple and universal vision. A vision to which each and every one of us can connect and contribute to its realisation. A vision based on the belief that by doing good deeds, positive thinking and affirmative choice of words, feelings and actions, we can enhance goodness in the world.

How true these beautiful and timeless words are. I learnt them well in my formative years, growing up in Tehran. We lived in Tehran Pars (Parsi Tehran), a mainly Zoroasterian founded and developed neighborhood inside the greater area of Tehran and located in the north east area of the city.

I attended Zoroasterian school and every morning we started our day by attending the morning assembly and reciting loudly: Think Good, Speak Good, Do Good.

This has served me well in my life. I cannot be grateful and thankful enough for those early years, growing up in Tehran Pars. Photo:quora.com

I have addressed these fundamental questions (as well as in the link above) in other places and times already. If what I have noted here makes sense to you and you wish to discover more, then, you can see the links below.

My first recommendation is the book I co-authored with my learned friend, Revd. Dr. Marcus Braybrooke, where we, together, tried to discuss as deeply as we could, some of these important questions and matters. The book was published in 2005.

Promoting the Common Good: A Theologian and an Economist in Dialogue

Please see below also:

Oxford Theology Society Lecture: Values to Make the World Great Again (Keble College, Oxford, March 2017)

Coventry and I: The story of a boy from Iran who became a man in Coventry ( A powerful reflection on how religion and religious leaders can be a message of hope and the common good)

Religion in Public Life (Kellogg College, Oxford, June 2008)

Theology, Philosophy, Ethics, Spirituality and Economics: A Call to Dialogue

This Easter Sunday, let's think about the kind of world we’d like to create

The future that awaits the human venture: A Story from a Wise and Loving Teacher

A Franciscan Environmental Restoration Path Engaging the Youth in Climate Change Adaptation

The Journey to Sophia: Education for Wisdom (A reflection on Buddhist values and spirituality and education)

What might an Economy for the Common Good look like? (Put it very simply, the common good has origins in the beginnings of Christianity. An early church father, John Chrysostom (c. 347–407),wrote: ‘This is the rule of most perfect Christianity, its most exact definition, its highest point, namely, the seeking of the common good . . . for nothing can so make a person an imitator of Christ as caring for his neighbours.’ Of course, all other religions say that we are indeed our neighbour’s keeper, and one way or another have time-honoured traditions on the common good…)

And in conclusion, a beautiful poem by Rumi, the Persian sage of love:

O You Who’ve gone on Pilgrimage

Come, Come, Whoever You Are, Come

Ours is not a caravan of despair.

Ours is a Journey of Hope

What You Seek Is Seeking You.

*around the world, people, and especially the youth, have turned their backs on religion

Religion declining in importance for many Americans, especially for Millennials